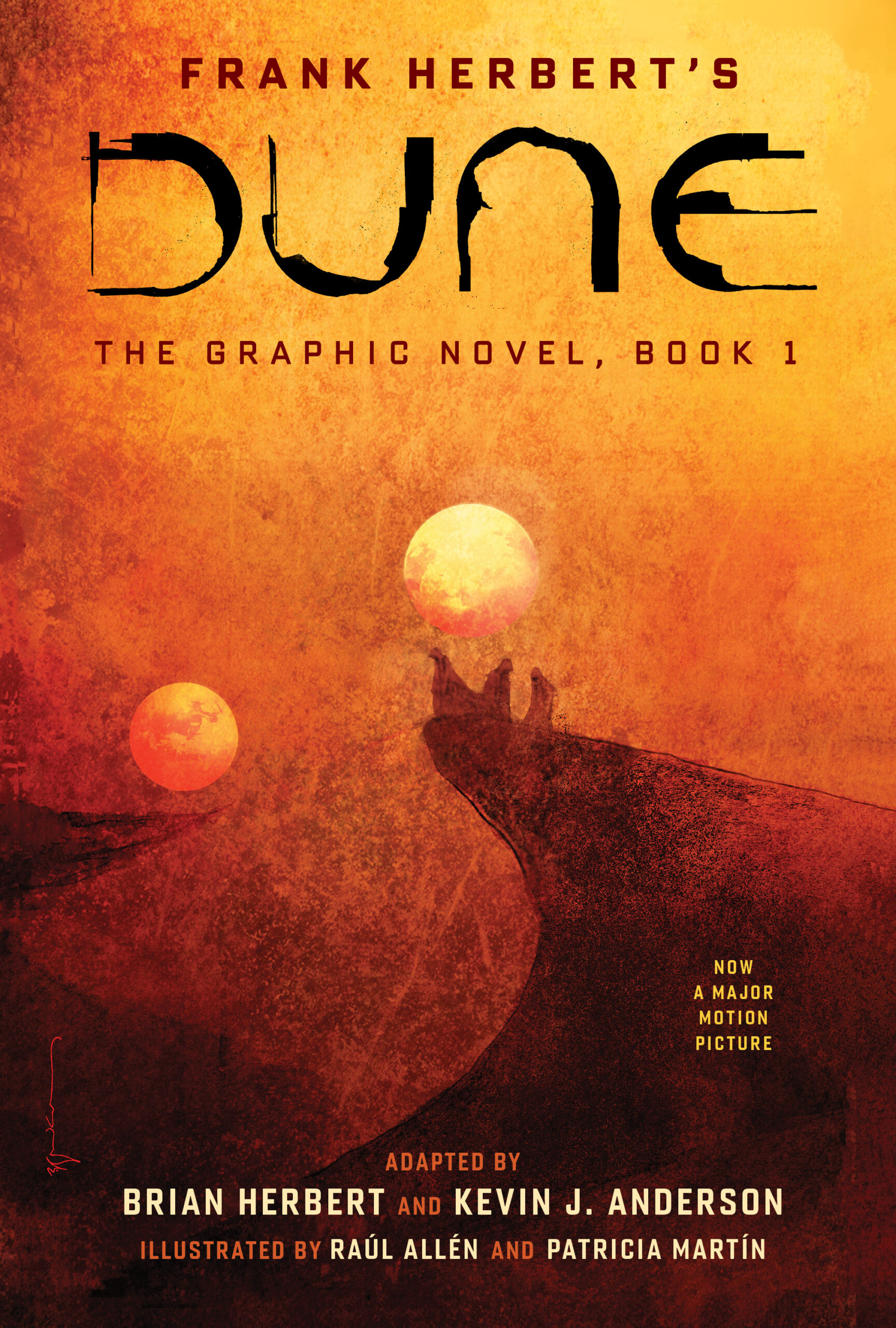

Like so many major motion pictures slated for a 2020 release, Denis Villeneuve’s Dune has been bumped into 2021. But fans of Frank Herbert’s epic science-fiction saga haven’t had to go entirely without adaptations this year, since last month saw the release of the first Dune graphic novel. Written by Kevin J. Anderson and Frank Herbert’s son Brian Herbert, co-authors of twelve Dune prequel and sequel novels, this 160-page volume constitutes just the first part of a trilogy intended to visually retell the story of the first Dune book. This tripartite breakdown seems to have been a wise move: the many adaptors (and would-be) adaptors of the linguistically, mythologically, and technologically complex novel have found out over the decades, it’s easy to bite off more Dune than you can chew.

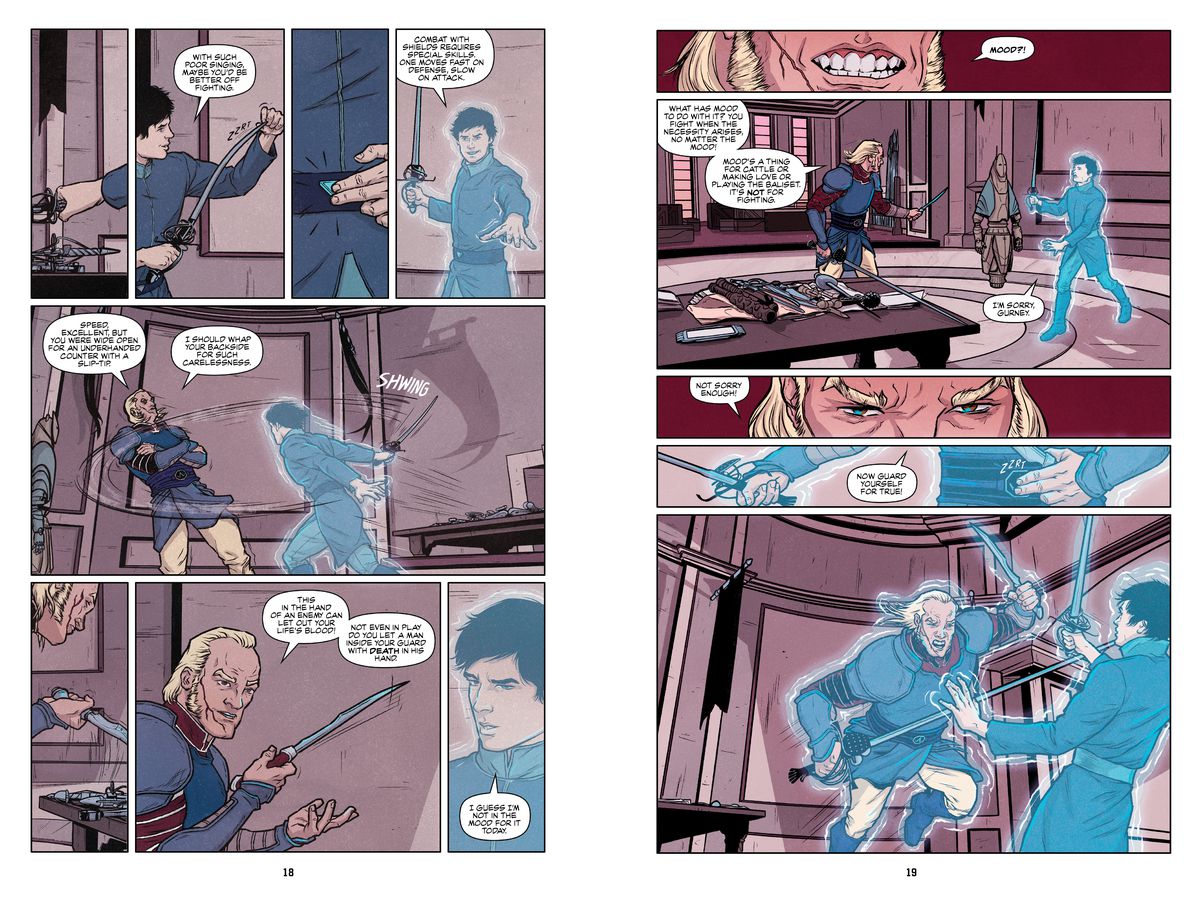

Audiences, too, can only digest so much Dune at a sitting themselves. “The particular challenge to adapting Dune, especially the early part, is that there is so much information to be conveyed — and in the novel it is done in prose and dialog, rather than action — we found it challenging to portray visually,” says Anderson in an interview with the Hollywood Reporter.

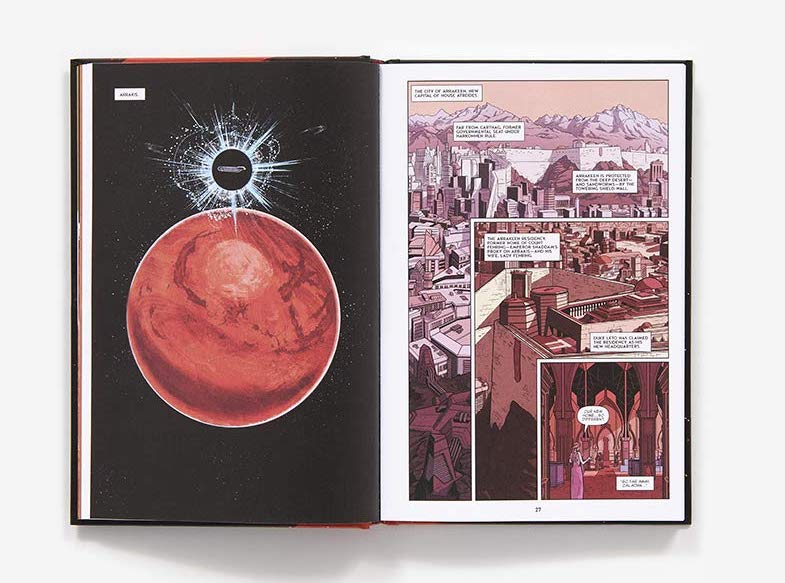

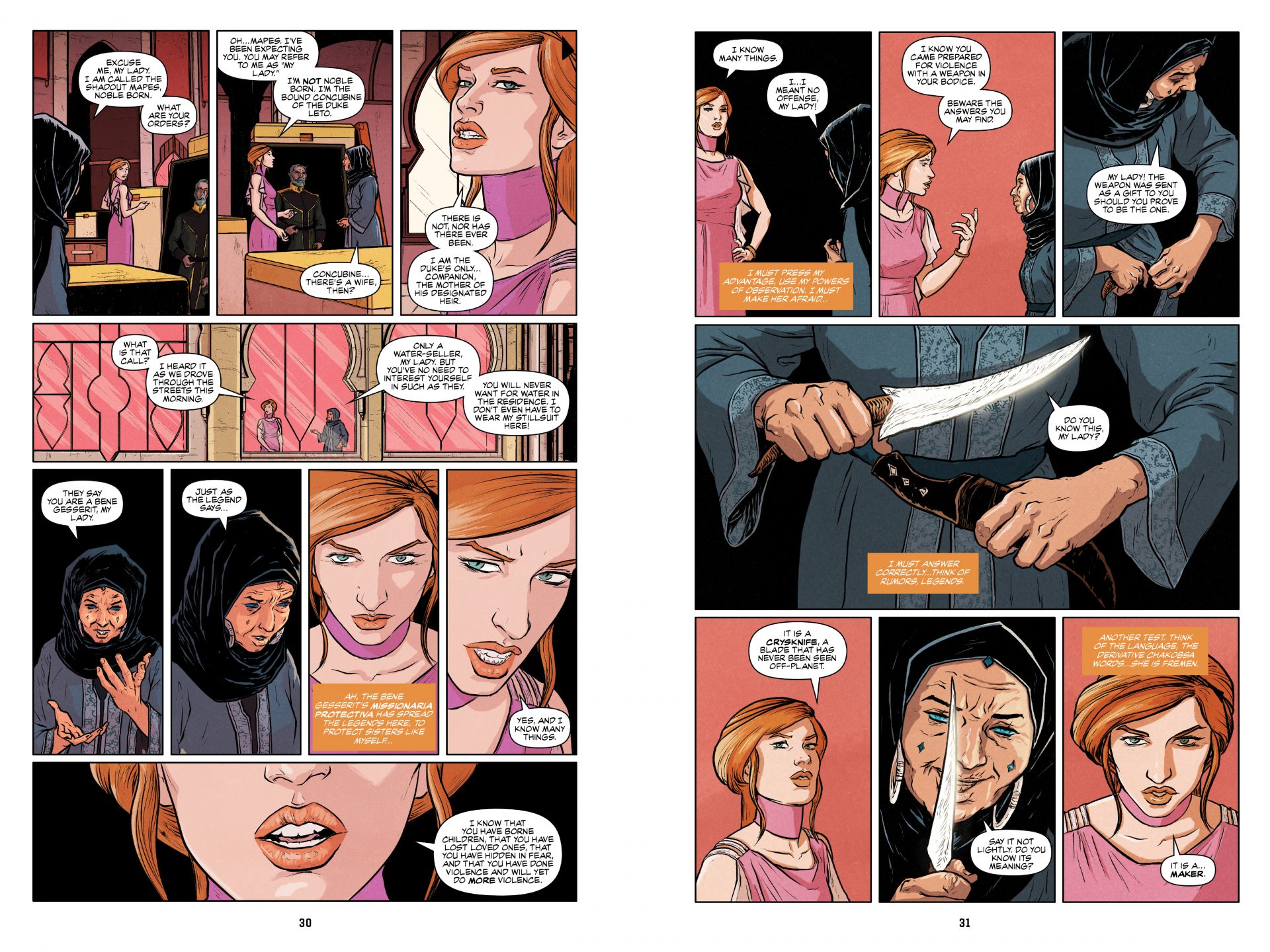

“Fortunately, the landscape is so sweeping, we could show breathtaking images as a way to convey that background.” This is the landscape of the desert planet Arrakis, source of a substance known as “spice.” Used as a fuel for space travel, spice has become the most precious substance in the galaxy, and its control is bitterly struggled over by numerous royal houses. (Any resemblance to Earth’s petroleum is, of course, entirely coincidental.)

The main narrative thread of the many running through Dune follows Paul Atreides, scion of the House Atreides. With his family sent to run Arrakis, Paul finds himself at the center of political intrigue, planetary revolution, and even a clandestine scheme to create a superhuman savior. Though Herbert and Anderson have produced a faithful adaptation, the graphic novel “trims the story down to its most iconic touchstone scenes,” as Thom Dunn puts it in his Boing Boing review (adding that it happens to focus in “a lot of the same scenes as David Lynch did with his gloriously messy film adaptation”). This streamlining also employs techniques unique to graphic novels: to retain the book‘s shifting omniscient narration, for example, “differently colored caption boxes present inner monologues from different characters like voiceovers so as not to interrupt the scene.”

As if telling the story of Dune at a graphic novel’s pace wasn’t task enough, Anderson, Herbert and their collaborators also have to convey its unusual and richly imagined world — in not just words, of course, but images. “Dune has had a lot of visual interpretations over the years, from Lynch’s bizarre pseudo-period piece treatment to the modern televised mini-series’ more gritty interpretation,” writes Polygon’s Charlie Hall. While “Villeneuve’s vibe appears to take its inspiration from more futuristic science fiction — all angles and chunky armor,” the graphic novel’s artists Raúl Allén and Patricia Martín “opt for something a bit more steampunk.” These choices all further what Brian Herbert describes as a mission to “bring a young demographic to Frank Herbert’s incredible series.” Such readers have shown great enthusiasm for stories of teenage protagonists who grow to assume a central role in the struggle between good and evil — not that, in the world of Dune, any conflict is quite so simple.

Related Content:

A Side-by-Side, Shot-by-Shot Comparison of Denis Villeneuve’s 2020 Dune and David Lynch’s 1984 Dune

Moebius’ Storyboards & Concept Art for Jodorowsky’s Dune

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, on Facebook, or on Instagram.

The Dune Graphic Novel: Experience Frank Herbert’s Epic Sci-Fi Saga as You’ve Never Seen It Before is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/3aiorEv

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment