We admire Johannes Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl Earring for many reasons, not least that it looks exactly like a girl with a pearl earring. Or at least it does from a distance, as the master of light himself no doubt stepped back to confirm countless times during the painting process, at any moment of which he would have been more concerned with the brushstrokes constituting only a small part of the image. But even Vermeer himself could have perceived only so much detail of the painting that would become his masterpiece.

Now, more than 350 years after its completion, we can get a closer view of Girl with a Pearl Earring than anyone has before through a newly released 10 billion-pixel panorama. At this resolution, writes Petapixel’s Jason Schneider, we can “see the painting down to the level of 4.4-microns per pixel.”

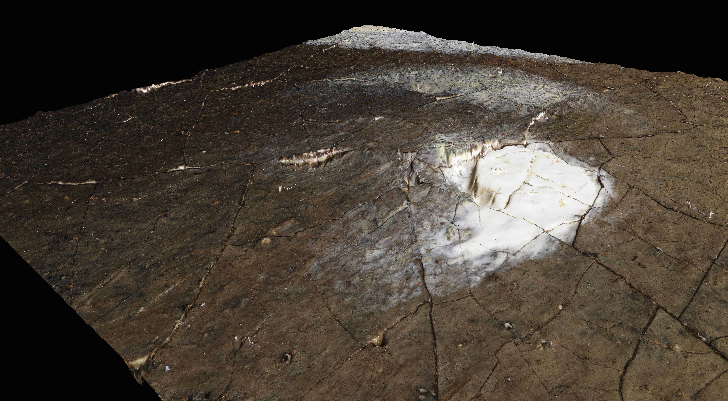

Undertaken by Emilien Leonhardt and Vincent Sabatier of 3D microscope maker Hirox Europe “in order to evaluate the surface condition of the painting, measure cracks, and see the topography of various key areas while assessing past restorations,” the project required taking 9,100 photos, which “were automatically captured and stitched together to form one finished panorama image where one pixel equals 4.4 microns.”

You’ll understand what this means if you view the panorama and click the plus symbol on the bottom control bar to zoom in — and click it again, and again, and again. (Or just click it and hold it down.) Before long, Girl with a Pearl Earring will look less like a girl with a pearl earring than what she really is: centuries-old oil paints on a centuries-old canvas. The physicality of this work of art, one so often held up as the realization of aesthetic ideal, becomes even less ignorable if you click the “3D” button. This presents ten individual sections of the painting scanned in three dimensions, which you can freely rotate and even light from all directions.

The 3D-scanned portions include the titular pearl earring, which appears to have a bit of a gouge in it. They’re more clearly visible in 5x topographical viewing mode (selectable on the top control bar). This official Hirox video offers a glimpse of the procedure required to achieve the kind of unprecedentedly high-resolution view of Girl with a Pearl Earring that allows us to behold details heretofore practically invisible. At more than 10,000 megapixels, the background reveals itself to be in fact a dark green curtain, and the girl herself has clearly defined eyelashes. But as for her long-speculated-about identity, well, there are some things microscopy can’t determine. Take a close look at Vermeer’s painting here.

via Colossal

Related Content:

Why is Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl Earring Considered a Masterpiece?: An Animated Introduction

Master of Light: A Close Look at the Paintings of Johannes Vermeer Narrated by Meryl Streep

Download All 36 of Jan Vermeer’s Beautifully Rare Paintings (Most in Brilliant High Resolution)

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletterBooks on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, on Facebook, or on Instagram.

A 10 Billion Pixel Scan of Vermeer’s Masterpiece Girl with a Pearl Earring: Explore It Online is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/3patETt

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment