I want every morning to be a new year’s for me. Every day I want to reckon with myself, and every day I want to renew myself. No day set aside for rest. I choose my pauses myself, when I feel drunk with the intensity of life and I want to plunge into animality to draw from it new vigour.

“Everyday is like Sunday,” sang the singer of our mopey adolescence, “In the seaside town that they forgot to bomb.” Somehow I could feel the grey malaise of post-industrial Britain waft across the ocean when I heard these words… the dreary sameness of the days, the desire for a conflagration to wipe it all away….

The call for total annihilation is not the sole province of supervillains and heads of state. It is the same desire Andrew Marvell wrote of centuries earlier in “The Garden.” The mind, he observed, “withdraws into its happiness” and creates “Far other worlds, and other seas; Annihilating all that’s made / To a green thought in a green shade.”

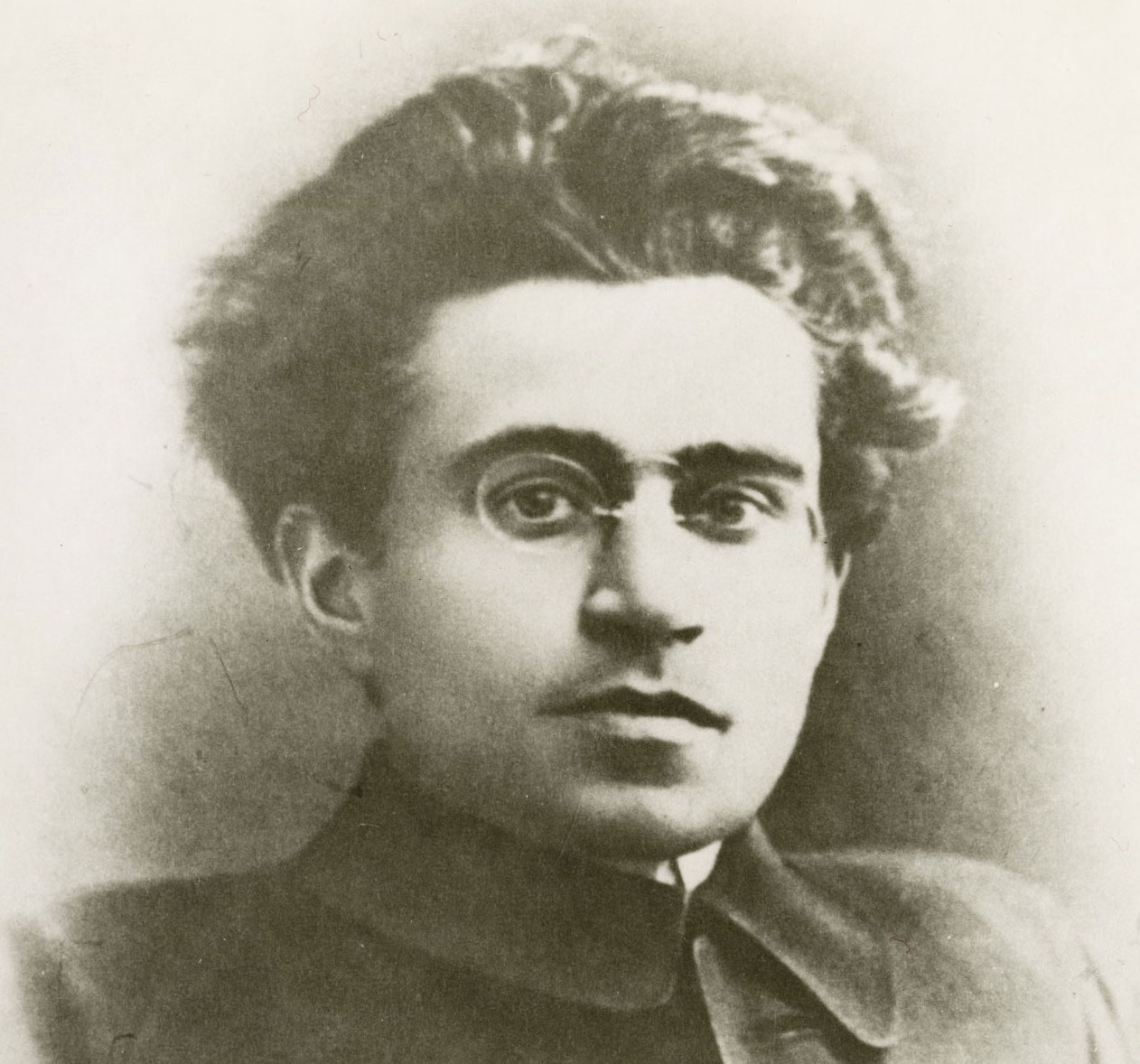

Is not annihilation what we seek each year on New Year’s Eve? To collectively wipe away the bad past by fiat, with fireworks? To welcome a better future in the morning, because an arbitrary record keeping system put in place before Marvell was born tells us we can? The problem with this, argued Italian Marxist party pooper and theorist Antonio Gramsci, is the problem with dates in general. We don’t get to schedule our apocalypses.

On January 1st, 1916, Gramsci published a column titled “I Hate New Year’s Day” in the Italian Socialist Party’s official paper Avanti!, which he began co-editing that year.

Every morning, when I wake again under the pall of the sky, I feel that for me it is New Year’s day.

That’s why I hate these New Year’s that fall like fixed maturities, which turn life and human spirit into a commercial concern with its neat final balance, its outstanding amounts, its budget for the new management. They make us lose the continuity of life and spirit. You end up seriously thinking that between one year and the next there is a break, that a new history is beginning; you make resolutions, and you regret your irresolution, and so on, and so forth. This is generally what’s wrong with dates.

The dates we keep, he says, are forms of “spiritual time-serving” imposed on us from without by “our silly ancestors.” They have become “invasive and fossilizing,” forcing life into repeating series of “mandatory collective rhythms” and forced vacations. But that is not how life should work, according to Gramsci.

Whether or not we find merit in his cranky pronouncements, or in his desire for socialism to “hurl into the trash all of these dates with have no resonance in our spirit,” we can all take one thing away from Gramsci’s critique of dates, and maybe make another resolution today: to make every morning New Year’s, to reckon with and renew ourselves daily, no matter what the calendar tells us to do. Read a full translation of Gramsci’s column at Viewpoint Magazine.

Related Content:

The Top 10 New Year’s Resolutions Read by Bob Dylan

Woody Guthrie’s Doodle-Filled List of 33 New Year’s Resolutions From 1943

Marilyn Monroe’s Go-Getter List of New Year’s Resolutions (1955)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Antonio Gramsci Writes a Column, “I Hate New Year’s Day” (January 1, 1916) is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/353mpoB

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment