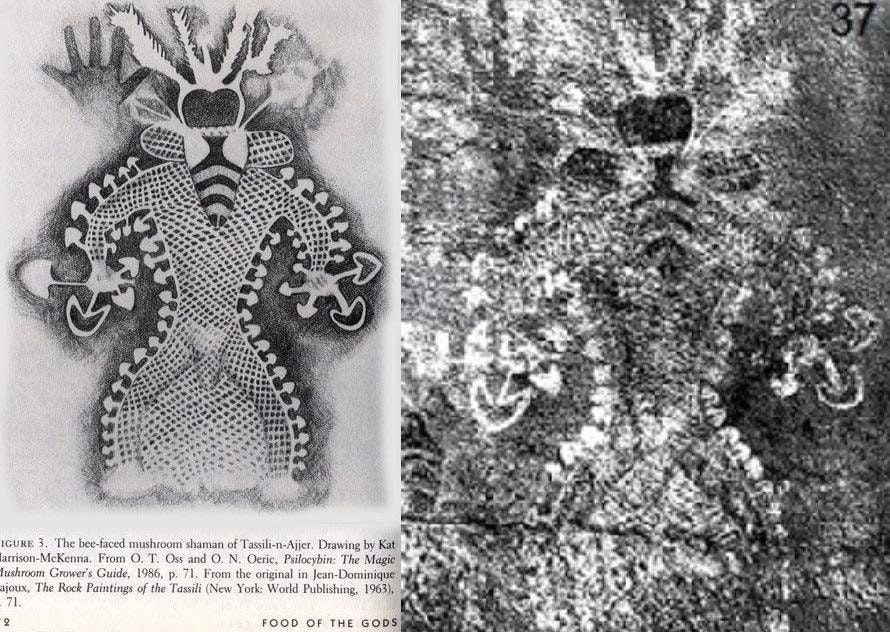

We moderns might wonder what ancient peoples did when not hunting, gathering, and reproducing. The answer is that they did mushrooms, at least according to one interpretation of cave paintings at Tassili n’Ajjer in Algeria, some of which go back 9,000 years. “Here are the earliest known depictions of shamans with large numbers of grazing cattle,” writes ethnobotanist/mystic Terence McKenna in his book Food of the Gods: The Search for the Original Tree of Knowledge. “The shamans are dancing with fists full of mushrooms and also have mushrooms sprouting out of their bodies. In one instance they are shown running joyfully, surrounded by the geometric structures of their hallucinations. The pictorial evidence seems incontrovertible.”

McKenna wasn’t the only scholar of the psychedelic experience to take an interest in Tassili. Giorgio Samorini had written about its ancient paintings a few years before, focusing on one that depicts “a series of masked figures in line and hieratically dressed or dressed as dancers surrounded by long and lively festoons of geometrical designs of different kinds.” Each dancer “holds a mushroom-like object in the right hand,” but the key visual element is the parallel lines that “come out of this object to reach the central part of the head of the dancer.” These “could signify an indirect association or non-material fluid passing from the object held in the right hand and the mind,” an interpretation in line with the idea of “the universal mental value induced by hallucinogenic mushrooms and vegetals, which is often of a mystical and spiritual nature.”

The U.S. Forest Service acknowledges Tassili as “the oldest known petroglyph depicting the use of psychoactive mushrooms,” adding the postulate that “the mushrooms depicted on the ‘mushroom shaman’ are Psilocybe mushrooms.” That name will sound familiar to 21st-century consciousness-alteration enthusiasts, some of whom advocate for the use of psilocybin, the psychedelic compound that occurs in such mushrooms, as not just a recreational drug but a treatment for conditions like depression. Cave art like Tassili’s suggests that such instrumental uses of hallucinogenic plants — as vital parts of rituals, for example — may stretch all the way back to the Neolithic era, when last the Sahara desert was a relatively verdant savanna rather than the vast expanse of sand we know today.

A sense of continuity with the practices of these long-ago predecessors — ancient Egyptians to the ancient Egyptians, as one Redditor frames it — must enrich mushroom use for many psychonauts today. And indeed, the “bee-headed shaman” and his compatriots have had a robust cultural afterlife: “A popularly published drawing based on one of the Tassili figures has become an icon of post-1990’s psychedelia,” says Brian Akers of Mushroom: The Journal of Wild Mushrooming. The “abstract-bizarre” style of its images have also put it “among the sites favored by ancient ET theorizing.” However rich the visions experienced by the cave-painters who once lived there, surely none could have been as mind-blowing as the idea that their work would still fire up imaginations nine millennia later.

via Reddit

Related Content:

Was a 32,000-Year-Old Cave Painting the Earliest Form of Cinema?

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Algerian Cave Paintings Suggest Humans Did Magic Mushrooms 9,000 Years Ago is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/3pr3JXV

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment