Rarely-Seen Illustrations of Dante’s Divine Comedy Are Now Free Online, Courtesy of the Uffizi Gallery

We know Dante’s Divine Comedy—especially its famous first third, Inferno—as an extended theological treatise, epic love poem, and vicious satire of church hypocrisy and the Florentine political faction that exiled Dante from the city of his birth in 1302. Most of us don’t know it the way its first readers did (and as Dante scholars do): a compendium in which “a number of medieval literary genres are digested and combined,” as Robert M. Durling writes in his translation of the Inferno.

These literary genres include vernacular traditions of romance poetry from Provence, popular long before Dante turned his Tuscan dialect into a literary language to rival Latin. They include “the dream-vision (exemplified by the Old French Romance of the Rose)”; “accounts of journeys to the Otherworld (such as the Visio Pauli, Saint Patrick’s Purgatory, the Navigatio Sancti Brendani)”; and Scholastic philosophical allegory, among other well-known forms of writing at the time.

By the time the Divine Comedy captured imaginations in the period of incunabula, or the infancy of the printed book, many of these associations and influences had receded. And by the time of the Counter-Reformation, the poem most impressed readers and illustrators of the text as a divine plan for a torture chamber and an encyclopedia of the tortures therein. Whatever other associations we have with Dante’s poem, we all know the nine circles of hell and have an ominous sense of what goes on there.

No doubt we also have in our mind’s eye some of the hundreds of illustrations made of the text’s gruesome depictions of hell, from Sandro Botticelli to Robert Rauschenberg. Illustrated editions of Dante’s poem began appearing in 1472, and the first fully illustrated edition in 1491. By the late 16th century, the poem had become a literary classic (the word Divine joined Comedy in the title in 1555). By this time, the tradition of depicting a literal, rather than a literary, hell was firmly established.

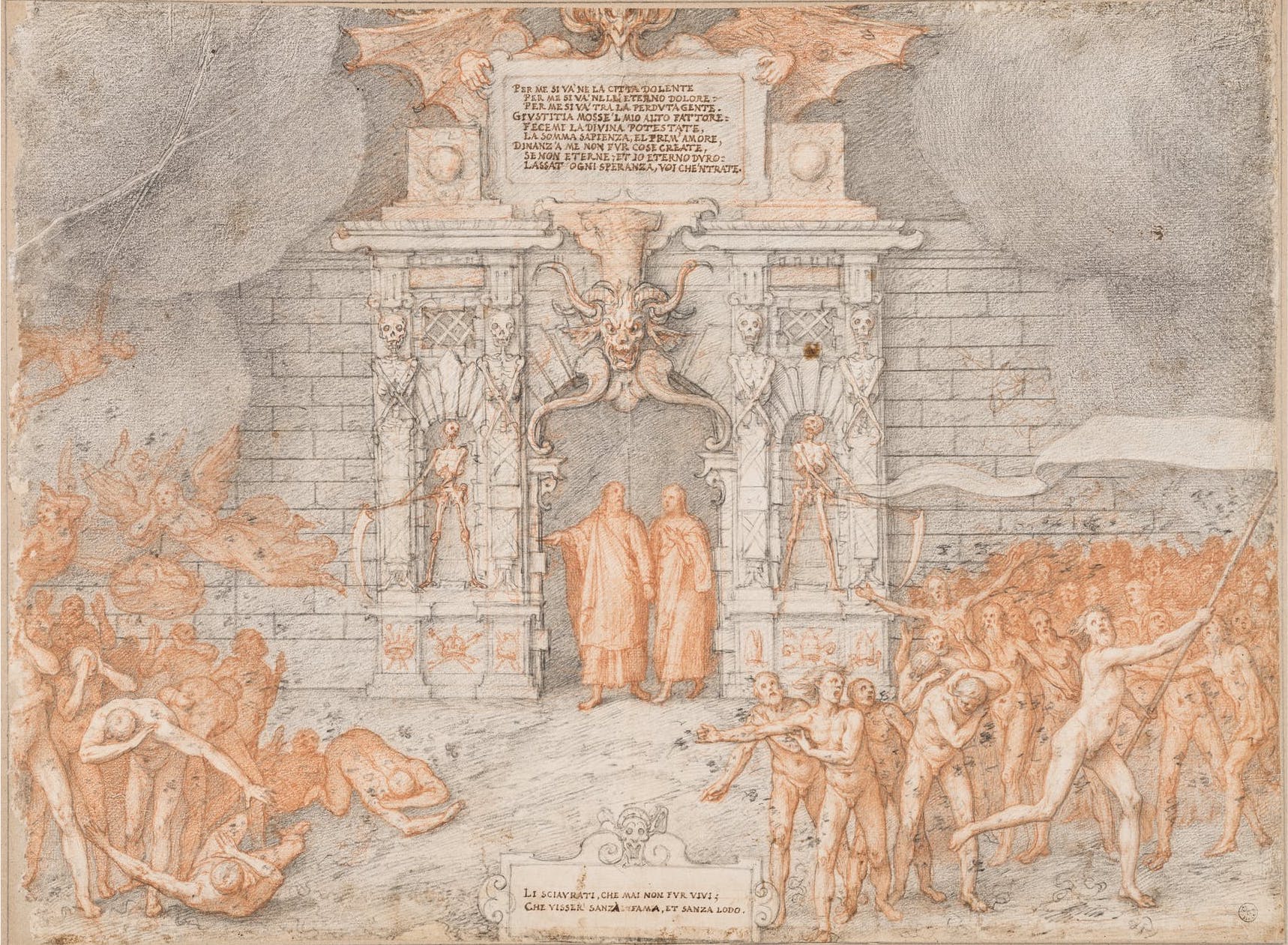

It was in this period that Frederico Zuccari made the beautiful illustrations you see here, completed, Angela Giuffrida writes at The Guardian, “during a stay in Spain between 1586 and 1588. Of the 88 illustrations, 28 are depictions of hell, 49 of purgatory and 11 of heaven. After Zuccari’s death in 1609, the drawings were held by the noble Orsini family, for whom the artist had worked, and later by the Medici family before becoming part of the Uffizi collection in 1738.”

The pencil-and-ink drawings have rarely been seen before because of their fragile condition. They were only exhibited publicly for the first time in 1865 for the 600th anniversary of Dante’s birth and of Italian unification. Now, they are on display, virtually, for free, as part of a “year-long calendar of events to mark the 700th anniversary of the poet’s death.” This is an extraordinary opportunity to see these illustrations, which have until now “only been seen by a few scholars and displayed to the public only twice, and only in part,” says Uffizi director Eike Schmidt.

Much of the promised “didactic-scientific comment” to accompany each drawing is marked as “upcoming” on the English version of the Uffizi site, but you can see high resolution scans of each drawing and zoom in to examine the many tortures of the damned and the grotesque demons who torment them. Learn much more at Khan Academy about how Dante’s literary epic in terza rima left “a lasting impression on the Western imagination for more than half a millennium,” solidifying and reshaping images of hell “into new guises that would become familiar to countless generations that followed.” If you like, you can also take a free course on Dante’s Divine Comedy from Yale University.

Related Content:

Why Should We Read Dante’s Divine Comedy? An Animated Video Makes the Case

A Digital Archive of the Earliest Illustrated Editions of Dante’s Divine Comedy (1487-1568)

Artists Illustrate Dante’s Divine Comedy Through the Ages: Doré, Blake, Botticelli, Mœbius & More

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Rarely-Seen Illustrations of Dante’s Divine Comedy Are Now Free Online, Courtesy of the Uffizi Gallery is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/2M2WoPw

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment