The early history of the bicycle did not promise great things—or anything, really—for women at the dawn of the 19th century. A two-wheeled bicycle-like invention, for example, built in 1820, “was more like an agricultural implement in construction than a bicycle,” one bicycle history notes. Made of wood, the “hobby horses” and velocipedes of cycling’s first decades rolled on iron wheels. Their near-total lack of suspension led to the epithet “boneshaker.” Some had steering mechanisms, some did not. Braking was generally accomplished with the feet, or a crowd of pedestrians, a tree, or horse-drawn cart.

Laddish clubs formed and raced around London, Paris, and New York. No girls allowed. The earliest bicycles for women were ridden side-saddle…. But despite all this, it is entirely fair to say that few technologies in history, ancient or modern, have done more to free women from domestic toilage and bring them careening into the public square, to the dismay of the Victorian establishment.

Bicycles “gave women a new level of transportation independence that perplexed newspaper columnists” and the general public, writes Adrienne LaFrance at The Atlantic, quoting a San Francisco journalist in 1895:

It really doesn’t matter much where this one individual young lady is going on her wheel. It may be that she’s going to the park on pleasure bent, or to the store for a dozen hairpins, or to call on a sick friend at the other side of town, or to get a doily pattern of somebody, or a recipe for removing tan and freckles. Let that be as it may. What the interested public wishes to know is, Where are all the women on wheels going? Is there a grand rendezvous somewhere toward which they are all headed and where they will some time hold a meet that will cause this wobbly old world to wake up and readjust itself?

Women cyclists were seen as the advanced guard of a coming war. “Squarely in the center of this battle was one tool,” notes the Vox video above, “that completely changed the game.” Both Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton are credited with declaring that ‘woman is riding to suffrage on the bicycle,’ a line that was printed and reprinted in newspapers at the turn of the century,” LaFrance writes. By the 1890s, everyone rode bicycles, the first Tour de France was only a few years away, and cycling technology had come so far that it would help create both the car—with its innovative pneumatic tires and spoked wheels—and the airplane, through the experiments of Ohio bicycle-makers the Wright Brothers.

The new bikes, originally called “safety bikes” to contrast them with giant-wheeled penny-farthings that were briefly the norm, may not have developed gearing systems yet, but they were far lighter, cheaper, and easier to ride (comparatively) than the bicycles that had come before, which began as playthings for wealthy young men-about-town. The National Women’s History Museum describes the scene:

At the turn of the century, trains, automobiles, and streetcars were growing in use in urban areas, but people still largely depended on horses for transportation. Horses, and especially carriages, were expensive and women often had to depend on men to hitch up the horses for travel…. Surrounded by inefficient and expensive forms of travel, bicycles arrived in cities with the promise of practicality and affordability. Bicycles were relatively inexpensive and provided men and women with individual transportation for business, sports, or recreation.

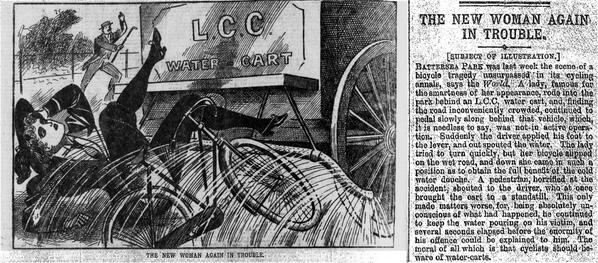

Not only did bicycles give women equal access to personal rapid transit, but they did so for women of many different social classes. The leveling effects were significant, as were the changes to women’s fashion. Exposed calves (though still encased in various cycling boots) prepared the way for trousers. Traditionalists were outraged, ceaselessly mocked women on bikes, as they mocked the suffragists, and pushed for restrictions on full freedom of movement. “Whilst the 1890s saw discourses of middle-class femininity become reconciled with the notion of women on bicycles,” The Victorian Cyclist points out, “learning to ride a bicycle required middle-class women to carefully navigate their way through a set of highly conservative and rigid gender norms.”

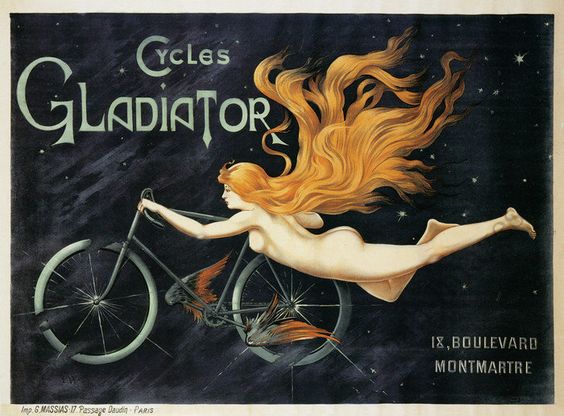

Despite media efforts to tamp down or tame the revolutionary potential of the bicycle for women, the market that made the machines saw no problem with increasing sales. Bicycle poster art and advertising from the turn of the 20th century is dominated by women cyclists, who are portrayed as ordinary ramblers about town, hip adventurers, ultra-modern “New Women,” and, perhaps less progressively, nude goddesses. Whether we call it Gilded Age, Belle Epoque, or Fin de siècle, the end of the 19th century produced a transportation revolution that was also, through no particularly conscious design of the makers of the bicycle, a revolution in women’s rights and thus human freedom writ large.

Related Content:

Odd Vintage Postcards Document the Propaganda Against Women’s Rights 100 Years Ago

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

How the Bicycle Helped Usher in the Women’s Rights Movement (Circa 1890) is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/3oP742U

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment