The printing history of early English books may not seem like the most fascinating subject in the world, but if you mention the name William Caxton to a book historian, you may get a fascinating lecture nonetheless. Caxton, the merchant and diplomat who introduced the printing press to England in 1476, was an unusually enterprising figure. He first learned the trade in Cologne and was pressured to begin printing in English after the success of his translation of the Recuyell of the Historyes of Troye, a series of stories based on Homer’s Iliad. His first known printed book was Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, and he went on to print translations of classical and medieval texts from the French.

Caxton’s (often inaccurate) translations became so popular that, like Chaucer, he introduced new standards into the language as a whole with his use of court Chancery English. The books printed at the time also give us a fascinating look at how the printed book evolved slowly as a new source of scientific information and a means of literary innovation.

The so-called Gutenberg Revolution did not usher in a radical break with the late medieval past so much as a gradual evolution away from its adherence to classical and church authorities and chivalric romance stories. It would take early modern writers like Shakespeare, Cervantes, and Francis Bacon to truly revolutionize the possibilities of print.

The first illustrated book Caxton printed in English offers an excellent example of early printing history’s reliance on reproducing extant medieval ideas rather than disseminating new ones. The Mirror of the World, first written in French as L’image du monde, was an encyclopedia based on a 12th century text by Honorius Augustodunensis called Imago mundi. “Encyclopedic texts were popular throughout the Middle Ages,” Glasgow University Library notes. “During this period it was commonly believed that it was possible to create one volume digests of all knowledge,” drawing solely on classical and Biblical authorities. In the introduction to Caxton’s text, we are told that the book “treateth of the world & of the wonderful dyuision [division] thereof.”

We are quite a long way yet from the Royal Society’s motto Nullius in verba, or “take no one’s word for it.” But Caxton’s press made several medieval manuscript prose works available for the first time to a new readership. “Evidence of early ownership of copies of his editions,” writes the British Library, “suggests the social breadth of that audience, including royalty, nobility, gentry, the mercantile classes and religious houses.” Caxton was “not content to simply draw on pre-existing markets for manuscripts.” And he would eventually use print “to create new markets for novel and different kinds of writing,” such as the 1485 publication of Thomas Malory’s contemporary Arthurian romance, Le Morte D’arthur.

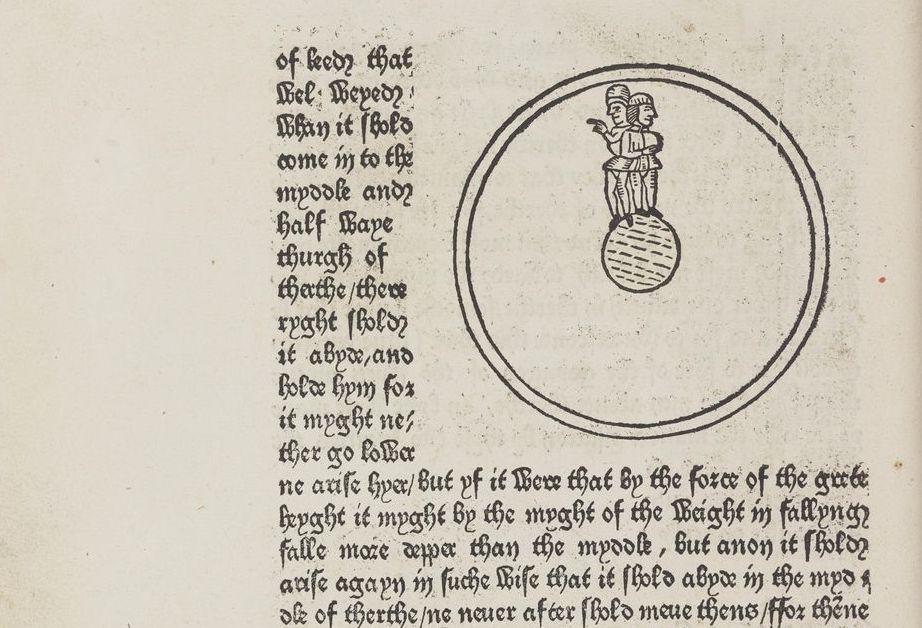

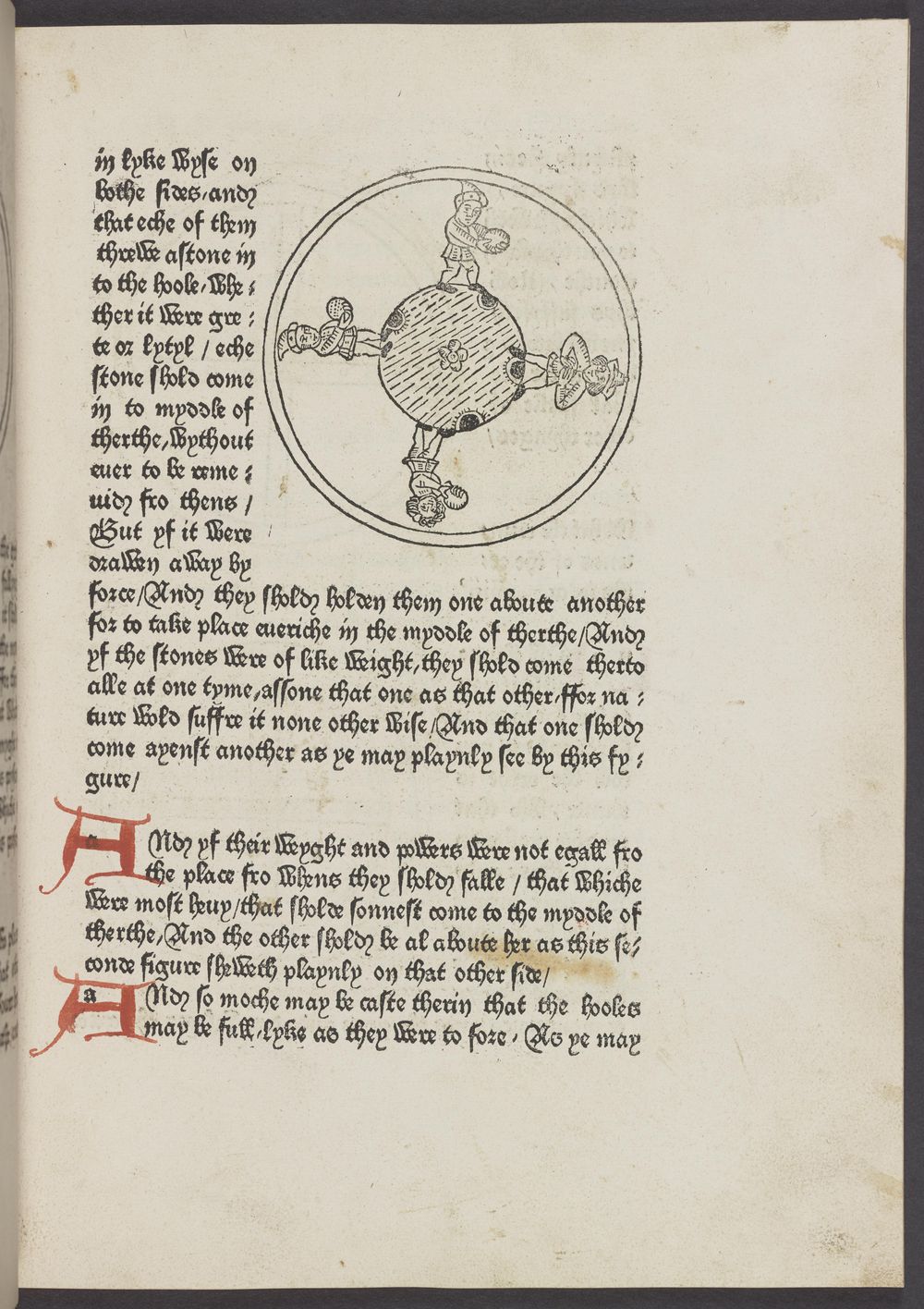

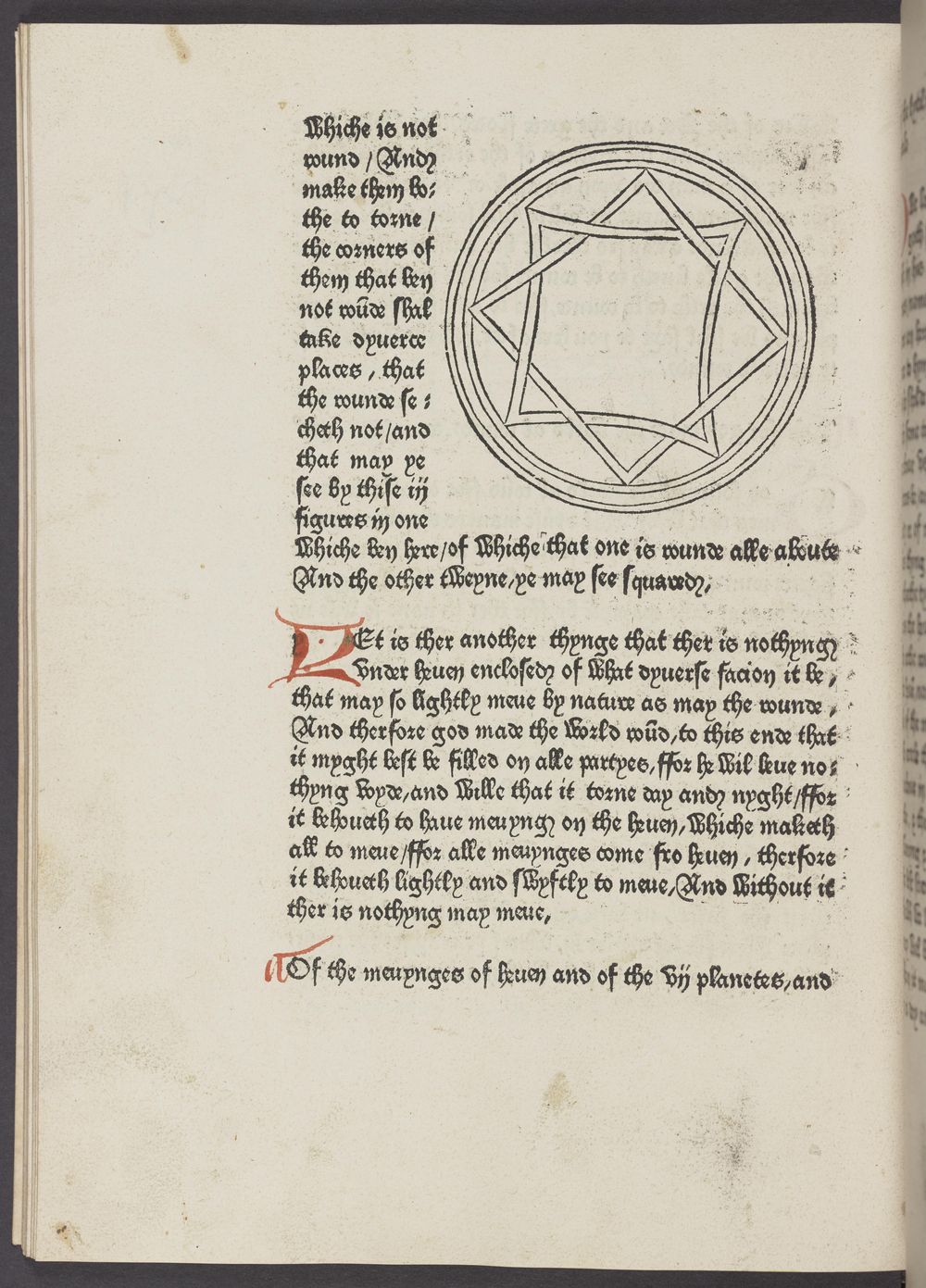

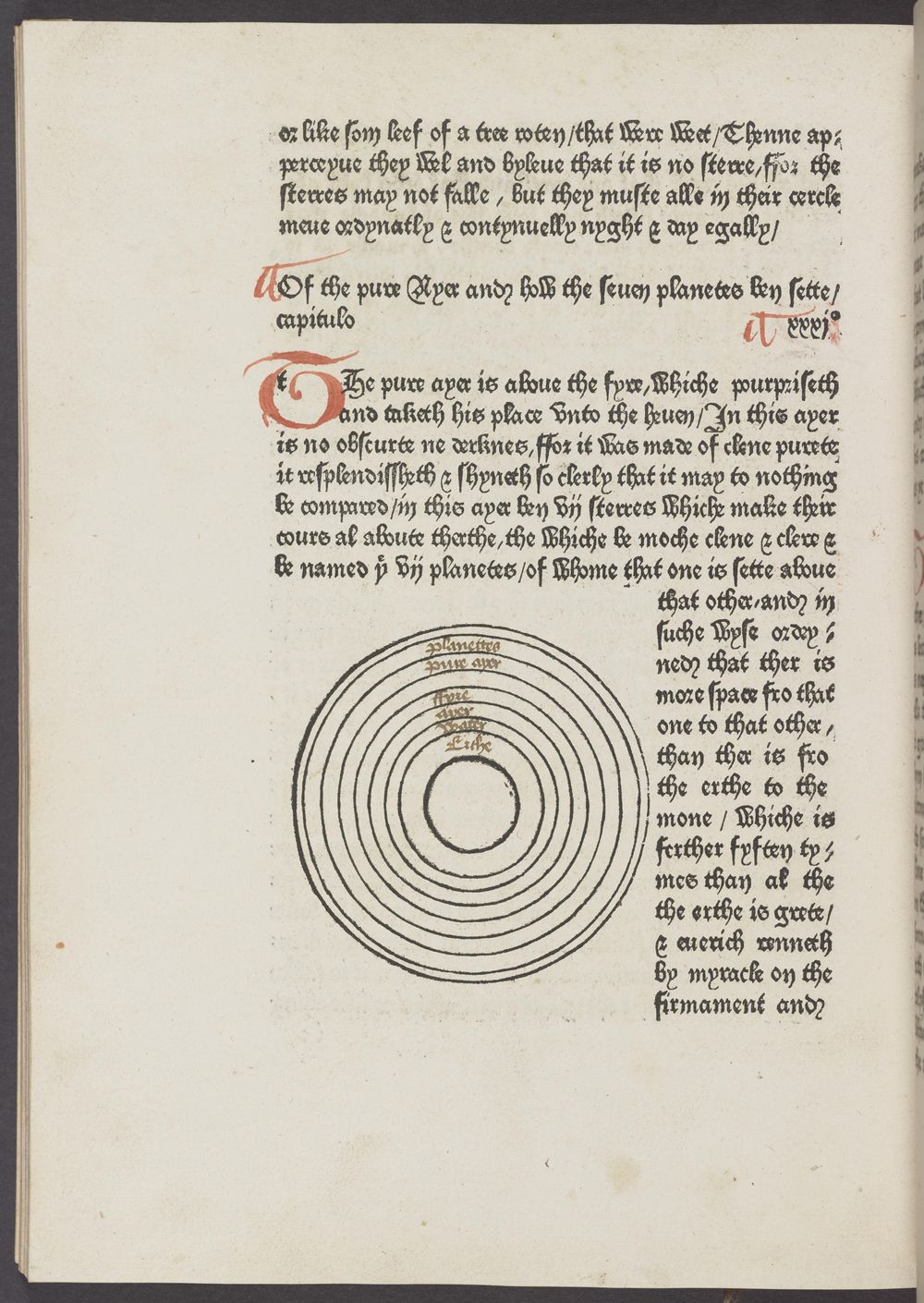

Representing the confident but cramped worldview of the medieval sciences, the Mirror of the World is “ambitious,” Allison Meier writes at Hyperallergic, dispelling any notion of a flat Earth, with descriptions of “large ideas like the roundness of the Earth and why we experience day and night… Along with some historical information, there are descriptions of the Earth, the solar system, and eclipses. The round shape of the Earth is illustrated by two men who stand back-to-back, walking away from each other and meeting again in a circle. Another describes the same idea with a rock tossed through a hole sliced in the world, with it tumbling out the other side.”

Mike Millward of the Blackburn Museum describes the images further:

The illustrations are woodcut prints which could be printed as part of the text. Caxton’s prints were probably produced in England and are rather primitive. Many are merely illustrative… Others are essential to an understanding of the text, such those illustrating the roundness of the Earth and the effect of gravity, both showing a surprisingly modern understanding

These illustrations, notes John T. McQuillan, assistant curator of printed books at the Pierpont Morgan library, were remarkably preserved from the original French text of two centuries earlier. “Print only carried on existing manuscript and textual traditions,” he notes, “and did not radically alter them, at first. Anyone who wanted to buy this text would have expected it to have these specific illustrations, and Caxton provided that to them.” Pierpont Morgan himself, who owned several of Caxton’s early printed books, “valued Caxton even over Gutenberg,” Meier writes, and “had the printer painted on the ceiling of his library’s East Room.”

Another rare books library, Princeton’s Scheide, which holds perhaps the finest collection of early European and American printing in the world, features a scanned full-text edition of Mirror of the World, the first illustrated book printed in England and a work that sits squarely on the threshold between the medieval and the modern, and that challenges our ideas about both designations.

Related Content:

One of World’s Oldest Books Printed in Multi-Color Now Opened & Digitized for the First Time

See the Oldest Printed Advertisement in English: An Ad for a Book from 1476

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Discover the First Illustrated Book Printed in English, William Caxton’s Mirror of the World (1481) is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/38D0FlI

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment