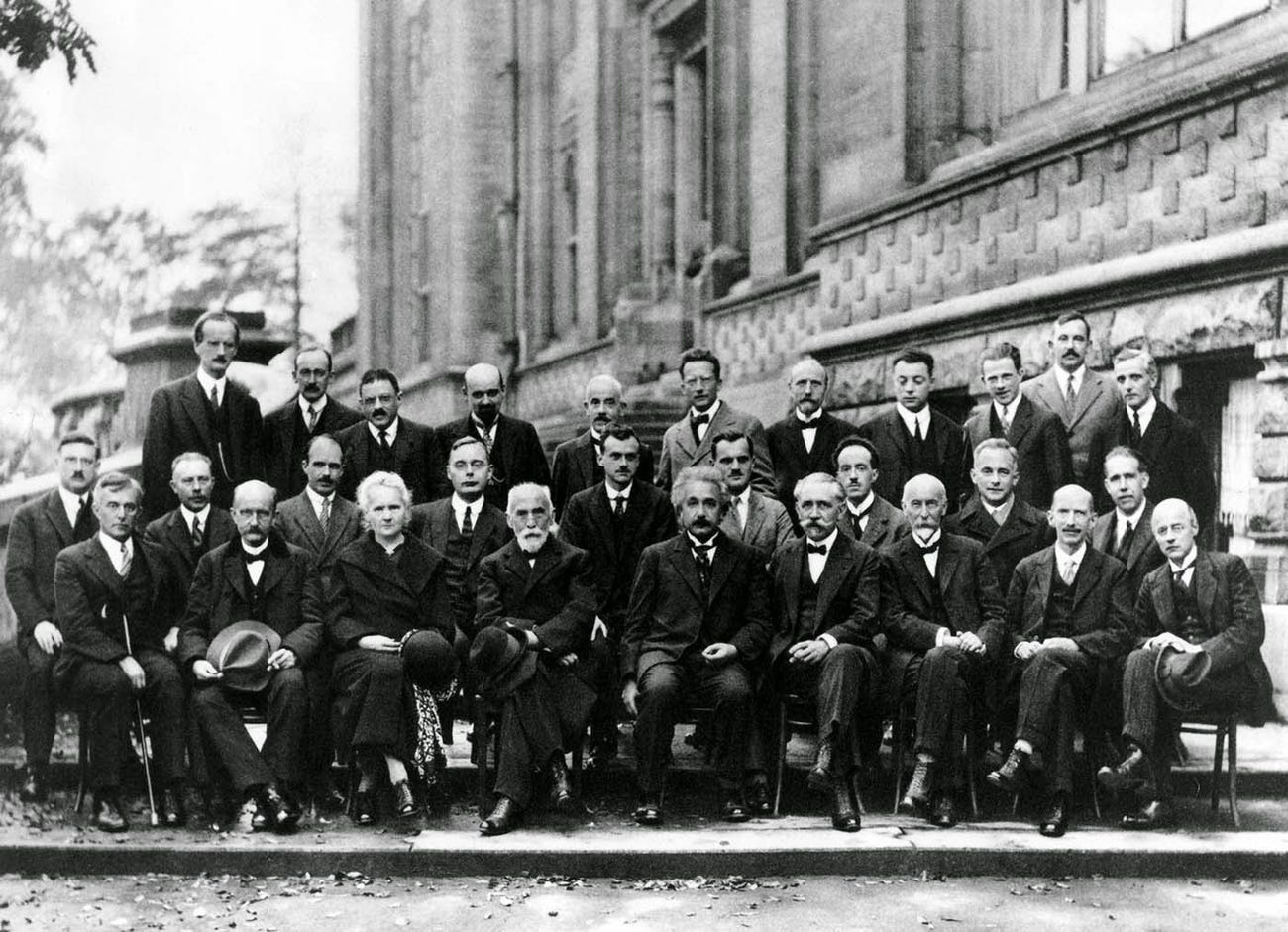

“The Most Intelligent Photo Ever Taken”: The 1927 Solvay Council Conference, Featuring Einstein, Bohr, Curie, Heisenberg, Schrödinger & More

A curious thing happened at the end of the 19th century and the dawning of the 20th. As European and American industries became increasingly confident in their methods of invention and production, scientists made discovery after discovery that shook their understanding of the physical world to the core. “Researchers in the 19th century had thought they would soon describe all known physical processes using the equations of Isaac Newton and James Clerk Maxwell,” Adam Mann writes at Wired. But “the new and unexpected observations were destroying this rosy outlook.”

These observations included X-rays, the photoelectric effect, nuclear radiation and electrons; “leading physicists, such as Max Planck and Walter Nernst believed circumstances were dire enough to warrant an international symposium that could attempt to resolve the situation.” Those scientists could not have known that over a century later, we would still be staring at what physicist Dominic Walliman calls the “Chasm of Ignorance” at the edge of quantum theory. But they did initiate “the quantum revolution” in the first Solvay Council, in Brussels, named for wealthy chemist and organizer Ernest Solvay.

“Reverberations from this meeting are still felt to this day… though physics may still sometimes seem to be in crisis” writes Mann (in a 2011 article just months before the discovery of the Higgs boson). The inaugural meeting kicked off a series of conferences on physics and chemistry that have continued into the 21st century. Included in the proceedings were Planck, “often called the father of quantum mechanics,” Ernest Rutherford, who discovered the proton, and Heike Kamerlingh-Onnes, who discovered superconductivity.

Also present were mathematician Henri Poincaré, chemist Marie Curie, and a 32-year-old Albert Einstein, the second youngest member of the group. Einstein described the first Solvay conference (1911) in a letter to a friend as “the lamentations on the ruins of Jerusalem. Nothing positive came out of it.” The ruined “temple,” in this case, were the theories of classical physics, “which had dominated scientific thinking in the previous century.” Einstein understood the dismay, but found his colleagues to be irrationally stubborn and conservative.

Nonetheless, he wrote, the scientists gathered at the Solvay Council “probably all agree that the so-called quantum theory is, indeed, a helpful tool but that it is not a theory in the usual sense of the word, at any rate not a theory that could be developed in a coherent form at the present time.” During the Fifth Solvay Council, in 1927, Einstein tried to prove that the “Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle (and hence quantum mechanics itself) was just plain wrong,” writes Jonathan Dowling, co-director of the Horace Hearne Institute for Theoretical Physics.

Physicist Niels Bohr responded vigorously. “This debate went on for days,” Dowling writes, “and continued on 3 years later at the next conference.” At one point, Einstein uttered his famous quote, “God does not play dice,” in a “room full of the world’s most notable scientific minds,” Amanda Macias writes at Business Insider. Bohr responded, “stop telling God what to do.” That room full of luminaries also sat for a portrait, as they had during the first Solvay Council meeting. See the assembled group at the top and further up in a colorized version in what may be, as one Redditor calls it, “the most intelligent picture ever taken.”

The full list of participants is below:

Front row: Irving Langmuir, Max Planck, Marie Curie, Hendrik Lorentz, Albert Einstein, Paul Langevin, Charles-Eugène Guye, C.T.R Wilson, Owen Richardson.

Middle row: Peter Debye, Martin Knudsen, William Lawrence Bragg, Hendrik Anthony Kramers, Paul Dirac, Arthur Compton, Louis de Broglie, Max Born, Niels Bohr.

Back row: Auguste Piccard, Émile Henriot, Paul Ehrenfest, Édouard Herzen, Théophile de Donder, Erwin Schrödinger, JE Verschaffelt, Wolfgang Pauli, Werner Heisenberg, Ralph Fowler, Léon Brillouin.

Related Content:

Quantum Physics Made Relatively Simple: A Mini Course from Nobel Prize-Winning Physicist Hans Bethe

The Map of Physics: Animation Shows How All the Different Fields in Physics Fit Together

Hear Albert Einstein Read “The Common Language of Science” (1941)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

“The Most Intelligent Photo Ever Taken”: The 1927 Solvay Council Conference, Featuring Einstein, Bohr, Curie, Heisenberg, Schrödinger & More is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/2M5fBjz

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment