How to Talk with a Conspiracy Theorist (and Why People Believe Conspiracy Theories in the First Place): What the Experts Recommend

Why do people pledge allegiance to views that seem fundamentally hostile to reality? Maybe believers in shadowy, evil forces and secret cabals fall prey to motivated reasoning. Truth for them is what they need to believe in order to get what they want. Their certainty in the justness of a cause can feel as comforting as a warm blanket on a winter’s night. But conspiracy theories go farther than private delusions of grandeur. They have spilled into the streets, into the halls of the U.S. Capitol building and various statehouses. Conspiracy theories about a “stolen” 2020 election are out for blood.

As distressing as such recent public spectacles seem at present, they hardly come near the harm accomplished by propaganda like Plandemic—a short film that claims the COVID-19 crisis is a sinister plot—part of a wave of disinformation that has sent infection and death rates soaring into the hundreds of thousands.

We may never know the numbers of people who have infected others by refusing to take precautions for themselves, but we do know that the number of people in the U.S. who believe conspiracy theories is alarmingly high.

A Pew Research survey of adults in the U.S. “found that 36% thought that these conspiracy theories” about the election and the pandemic “were probably or definitely true,” Tanya Basu writes at the MIT Technology Review. “Perhaps some of these people are your family, your friends, your neighbors.” Maybe you are conspiracy theorist yourself. After all, “it’s very human and normal to believe in conspiracy theories…. No one is above [them]—not even you.” We all resist facts, as Cass Sunstein (author of Conspiracy Theories and Other Dangerous Ideas) says in the Vox video above, that contradict cherished beliefs and the communities of people who hold them.

So how do we distinguish between reality-based views and conspiracy theories if we’re all so prone to the latter? Standards of logical reasoning and evidence still help separate truth from falsehood in laboratories. When it comes to the human mind, emotions are just as important as data. “Conspiracy theories make people feel as though they have some sort of control over the world,” says Daniel Romer, a psychologist and research director at the University of Pennsylvania’s Annenberg Public Policy Center. They’re airtight, as Wired shows below, and it can be useless to argue.

Basu spoke with experts like Romer and the moderators of Reddit’s r/ChangeMyView community to find out how to approach others who hold beliefs that cause harm and have no basis in fact. The consensus recommends proceeding with kindness, finding some common ground, and applying a degree of restraint, which includes dropping or pausing the conversation if things get heated. We need to recognize competing motivations: “some people don’t want to change, no matter the facts.”

Unregulated emotions can and do undermine our ability to reason all the time. We cannot ignore or dismiss them; they can be clear indications something has gone wrong with our thinking and perhaps with our mental and physical health. We are all subjected, though not equally, to incredible amounts of heightened stress under our current conditions, which allows bad actors like the still-current U.S. President to more easily exploit universal human vulnerabilities and “weaponize motivated reasoning,” as University of California, Irvine social psychologist Peter Ditto observes.

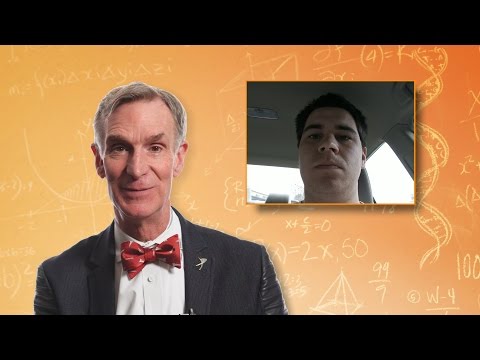

To help counter these tendencies in some small way, we present the resources above. In Bill Nye’s Big Think answer to a video question from a viewer named Daniel, the longtime science communicator talks about the discomfort of cognitive dissonance. “The way to overcome that,” he says, is with the attitude, “we’re all in this together. Let’s learn about this together.”

We can perhaps best approach those who embrace harmful conspiracy theories by not immediately telling them that we know more than they do. It’s a conversation that requires some intellectual humility and acknowledgement that change is hard and it feels really scary not to know what’s going on. Below, see an abridged version of MIT Technology Review’s ten tips for reasoning with a conspiracy theorist, and read Basu’s full article here.

- Always, always speak respectfully: “Without respect, compassion, and empathy, no one will open their mind or heart to you. No one will listen.”

- Go private: Using direct messages when online “prevents discussion from getting embarrassing for the poster, and it implies a genuine compassion and interest in conversation rather than a desire for public shaming.”

- Test the waters first: “You can ask what it would take to change their mind, and if they say they will never change their mind, then you should take them at their word and not bother engaging.”

- Agree: “Conspiracy theories often feature elements that everyone can agree on.”

- Try the “truth sandwich”: “Use the fact-fallacy-fact approach, a method first proposed by linguist George Lakoff.”

- Or use the Socratic method: This “challenges people to come up with sources and defend their position themselves.”

- Be very careful with loved ones: “Biting your tongue and picking your battles can help your mental health.”

- Realize that some people don’t want to change, no matter the facts.

- If it gets bad, stop: “One r/ChangeMyView moderator suggested ‘IRL calming down’: shutting off your phone or computer and going for a walk.”

- Every little bit helps. “One conversation will probably not change a person’s mind, and that’s okay.”

Related Content:

Constantly Wrong: Filmmaker Kirby Ferguson Makes the Case Against Conspiracy Theories

Neil Armstrong Sets Straight an Internet Truther Who Accused Him of Faking the Moon Landing (2000)

Michio Kaku & Noam Chomsky School Moon Landing and 9/11 Conspiracy Theorists

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

How to Talk with a Conspiracy Theorist (and Why People Believe Conspiracy Theories in the First Place): What the Experts Recommend is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/3sp0QZM

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment