His were usually humorous stories, full of magic, and very often, they contained a connection to the children’s lives, because it was primarily for them that he invented them.

–Sarah Zama

The fact that “much of the inspiration of the Lord of the Rings came from [J.R.R. Tolkien’s] family,” Danielle Burgos writes at Bustle, has become an oft-repeated piece of trivia, especially thanks to such popular treatments of the author’s life as Humphrey Carter’s authorized biography, the Nicholas Hoult-starring biopic, Tolkien, and the Catherine McIlwaine-edited collection Tolkien: Maker of Middle-Earth. As much as Tolkien drew on his extensive knowledge of Norse, Germanic, and other mythologies and linguistic histories, and from his harrowing experiences in WWI, his career as a legendary fantasy author may never have come about without his children.

“In just one example,” notes Burgos, a collection of Tolkien’s letters shows that the character of Tom Bombadil “was based on son Michael’s wooden toy doll.” Tolkien’s oldest son John remarked before the release of the first Peter Jackson adaptation, “It’s quite incredible. When I think when we were growing up these were just stories that we were told.”

Tolkien strenuously resisted the label of children’s author; he “firmly believed,” Maria Popova points out, “that there is no such thing as writing for children.” But the degree to which his storytelling and characterization developed from his desire to entertain and educate his kids can’t be overstated in the development of his early fiction.

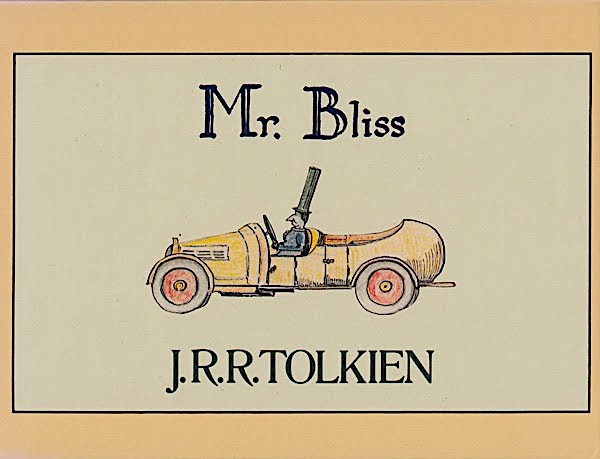

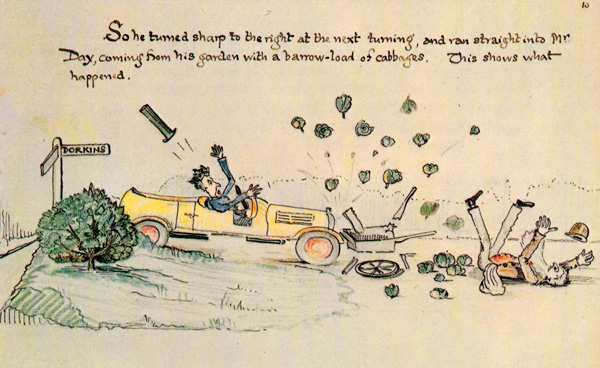

We see this in a small way in the little-known children’s book Mr. Bliss, written and illustrated by Tolkien sometime in the 1930s, kept in a drawer until 1957, and only published posthumously in 1982. The story itself “was inspired by his first car, which he purchased in 1932.” As evidence of its importance to the larger Tolkien canon, Popova writes, the author “went on to use two of the character names from the book, Gaffer Gamgee and Boffin, in The Lord of the Rings.” In other respects, however, Mr. Bliss is very unlike the medieval fantasies that surrounded its composition.

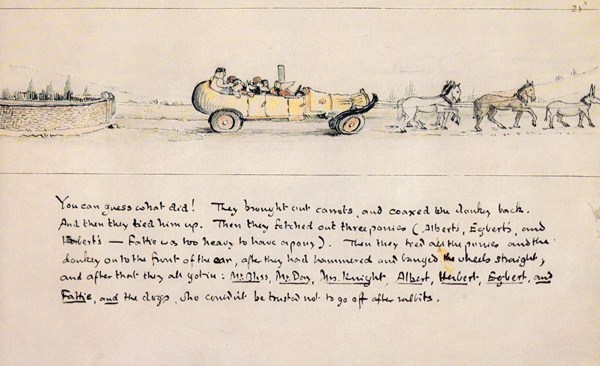

The book, affectionately handwritten and illustrated by Tolkien himself — who, also unbeknownst to many, was a dedicated artist — tells the story of Mr. Bliss, a lovable eccentric known for his exceptionally tall hats and his “girabbits,” the giraffe-headed, rabbit-bodied creatures that live in his backyard. One day, Mr. Bliss decides to buy his very first motor car[.] But his first drive en route to a friend’s house soon turns into a Rube Goldberg machine of disaster as he collides with nearly everything imaginable, then gets kidnapped by three bears.

Tolkien submitted the book for publication after the runaway success of The Hobbit created a market demand he had no particular desire to meet, telling his publisher that the story was complete. But Mr. Bliss was rejected, ostensibly because its illustrations were too expensive to reproduce. In truth, however, the public wanted more hobbits, elves, dwarves, wizards, and poetry and song in beautiful invented languages.

Tolkien would, of course, eventually deliver a “New Hobbit,” in the form of the The Lord of the Rings trilogy—books that weren’t specifically “written for his children,” Sarah Zama writes, but in which “the story he had indeed created for his children weighed heavily.” See several more Tolkien-illustrated pages from one of the trilogy’s whimsical early ancestors, Mr. Bliss, at Brain Pickings and purchase a copy of the book here.

Related Content:

110 Drawings and Paintings by J.R.R. Tolkien: Of Middle-Earth and Beyond

How J.R.R. Tolkien Influenced Classic Rock & Metal: A Video Introduction

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Discover J.R.R. Tolkien’s Little-Known and Hand-Illustrated Children’s Book, Mr. Bliss is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/3rQfrwZ

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment