For those with the time, skill, and drive, LEGO is the perfect medium for wildly impressive recreations of iconic structures, like the Taj Mahal, Eiffel Tower, the Titanic and now the Roman Colosseum.

But water? A wave?

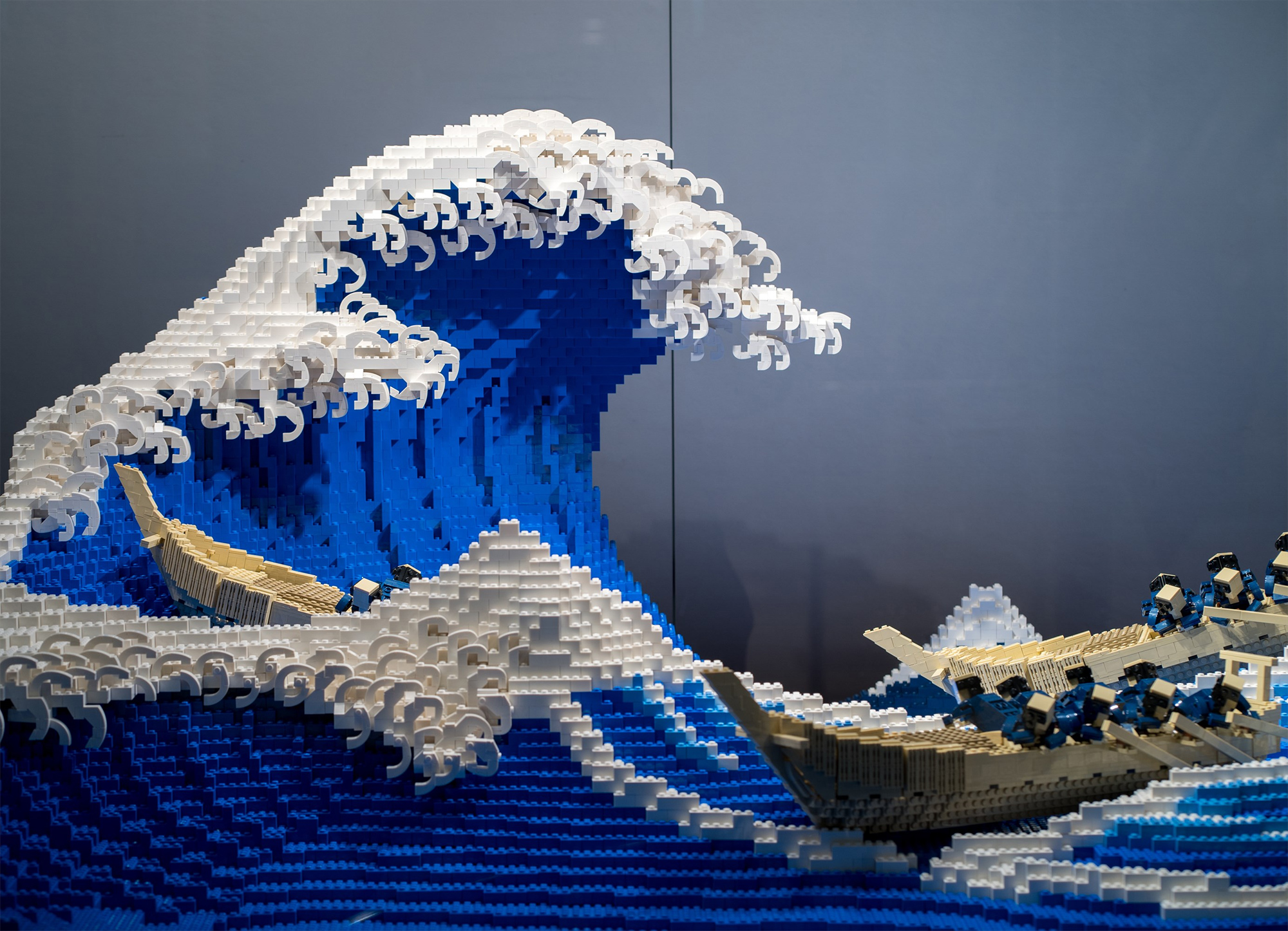

And not just any wave, but Katsushika Hokusai‘s celebrated 19th-century woodblock print, The Great Wave off Kanagawa.

As Open Culture’s Colin Marshall pointed out earlier, you might not know the title, but the image is instantly recognizable.

Artist Jumpei Mitsui, the world’s youngest LEGO Certified Professional, was undeterred by the thought of tackling such a dynamic and well known subject.

While other LEGO enthusiasts have created excellent facsimiles of famous artworks, doing justice to the curves and implied motion of The Great Wave seems a nearly impossible feat.

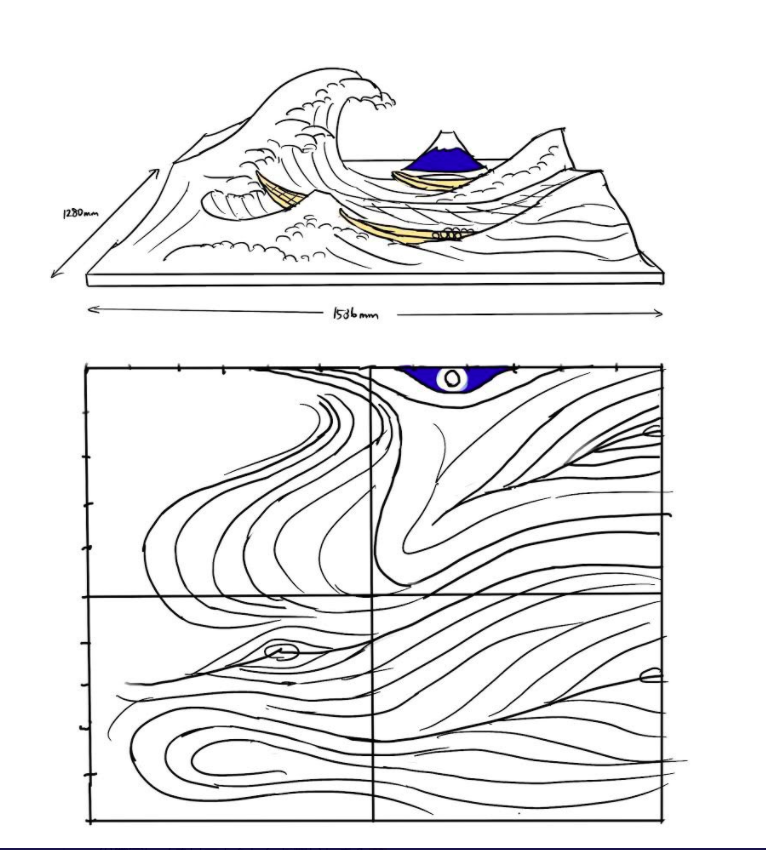

Having spent his childhood in a house by the sea, waves are a familiar presence to Mitsui. To get a better sense of how they work, he read several scientific papers and spent four hours studying wave videos on YouTube.

He made only one preparatory sketch before beginning the build, an effort that required 50,000 some LEGO pieces.

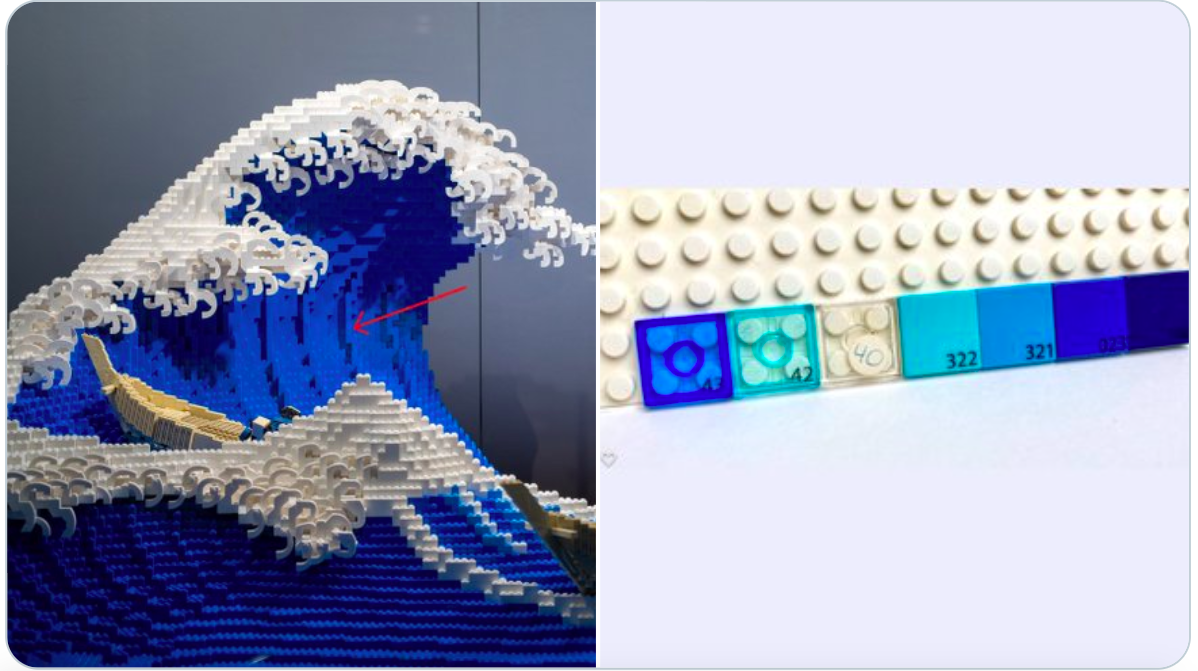

His biggest hurdle was choosing which color bricks to use in the area indicated by the red arrow in the photo below. Hokusai had taken advantage of the newly affordable Berlin blue pigment in the original.

Mitsui tweeted:

I tried a total of 7 colors including transparent parts, but in the end, I adopted the same blue color as the waves. If you use other colors, the lines will be overemphasized and unnatural, but if you use blue, the shade will be created just by adjusting the light, and the natural lines will appear nicely. It can be said that it was possible because it was made three-dimensional.

Jumpei Mitsui’s wave is now on permanent view at Osaka’s Hankyu Brick Museum.

via Spoon and Tamago and Colossal

Related Content:

The Frank Lloyd Wright Lego Set

With 9,036 Pieces, the Roman Colosseum Is the Largest Lego Set Ever

Why Did LEGO Become a Media Empire? Pretty Much Pop: A Culture Podcast #37

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. She most recently appeared as a French Canadian bear who travels to New York City in search of food and meaning in Greg Kotis’ short film, L’Ourse. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

Hokusai’s Iconic Print, “The Great Wave off Kanagawa,” Recreated with 50,000 LEGO Bricks is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/2J12w9K

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment