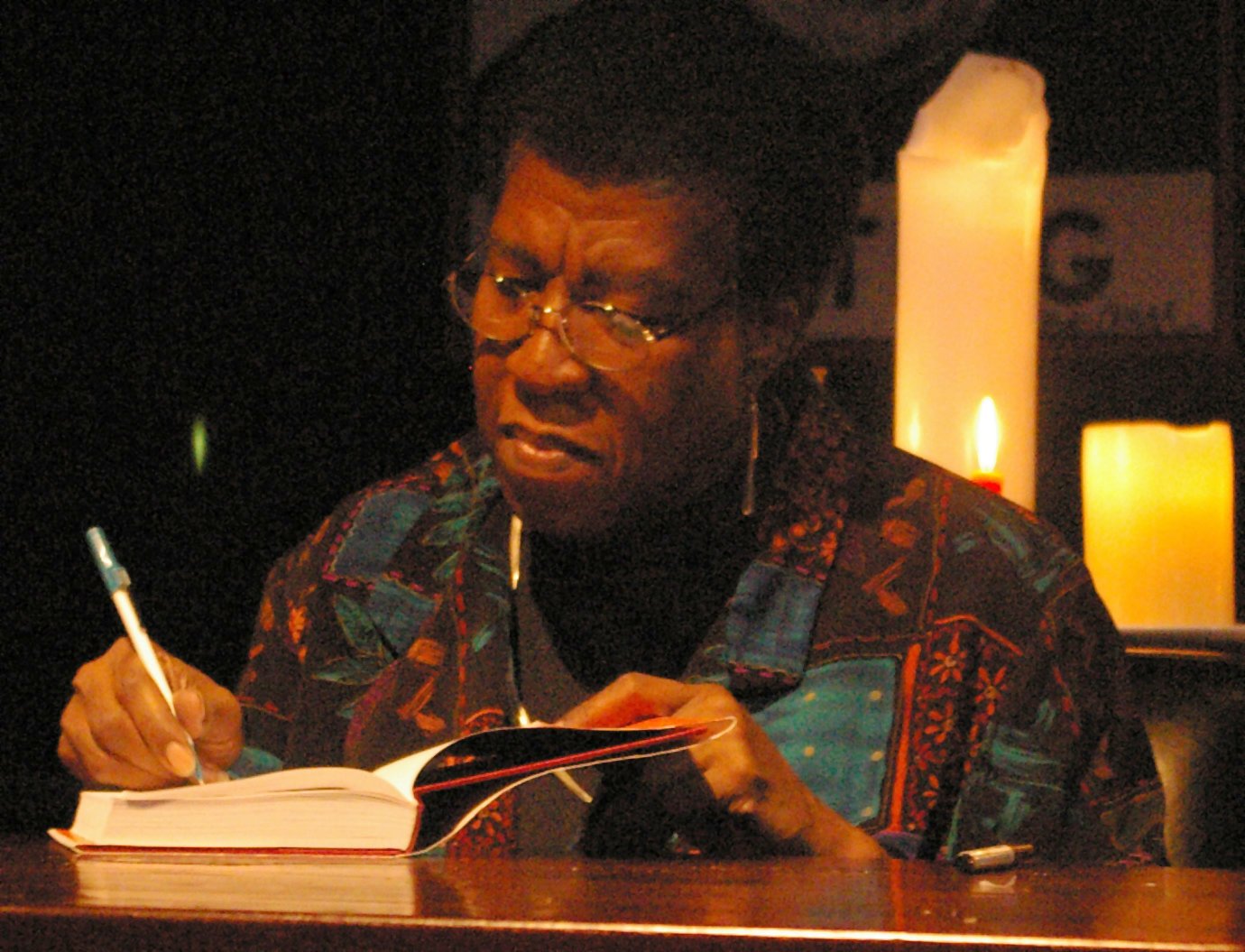

Image by Nikolas Coukouma, via Wikimedia Commons

If you, like me, often turn to science fiction to get more clarity about the present, past, and future, then you know you’re in good company with multiple-award-winning sci-fi author Octavia Butler. The novelist cast her gaze over it all, looking into the dark corners of American life and human behavior and drawing out stories that feel both shockingly new and familiar and true.

Sometimes Butler’s truths are hard to hear, especially when we’re living in the midst of a time she foresaw with such seeming accuracy thirty years ago in her Parable novels, two books meant to be the first parts of a trilogy about America’s greed, cruelty, and racism swallowing up its good intentions and inflated self-image.

Parable of the Sower and Parable of the Talents are, as Butler described them, “novels that take place in a near future of increasing drug addiction and illiteracy, marked by the popularity of prisons and the unpopularity of public schools, the vast and growing gap between the rich and everyone else, and the whole nasty family of problems brought on by global warming.”

These problems include the return of debt slavery, a particularly nasty strain of Christian nationalism, and a vague but devastating environmental collapse from which there is no return. But these are also novels about hope: about survival and adaptation and empathy. Butler may have invented the plots of her post-apocalyptic future, but “I didn’t make up the problems,” she once told a student.

Science fiction writers aren’t clairvoyant, they’re just better at making observations and speculations. “All I did was look around at the problems we’re neglecting now and give them about 30 years to grow into full-fledged disasters,” said Butler. A perspective that doesn’t also include the whole of human history is bound to miss the mark, she suggested:

Writing novels about the future doesn’t give me any special ability to foretell the future. But it does encourage me to use our past and present behaviors as guides to the kind of world we seem to be creating. The past, for example, is filled with repeating cycles of strength and weakness, wisdom and stupidity, empire and ashes. To study history is to study humanity. And to try to foretell the future without studying history is like trying to learn to read without bothering to learn the alphabet.

Butler goes on to discuss her method for predicting the future—so to speak—which anyone can learn to do with enough study and insight (that’s the hard part). Thom Dunn at Boing Boing has helpfully broken down her essay’s main points into four concise rules:

- Learn from the past

- Respect the law of consequences

- Be aware of your perspective

- Count on the surprises

You can read the full essay here and get to work on your own forecasting abilities. But in order to fully understand Butler’s project, it is essential never to despair. “The one thing that I and my main characters never do when contemplating the future is give up hope,” she writes. In answer to her student’s anguished question, if things are going to get so bad “what’s the answer?” Butler sagely replied, “there isn’t one…. There’s no magic bullet. Instead there are thousands of answers—at least. You can be one of them if you choose to be.”

via Boing Boing

Related Content:

Behold Octavia Butler’s Motivational Notes to Self

Why Should We Read Pioneering Sci-Fi Writer Octavia Butler? An Animated Video Makes the Case

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Octavia Butler’s Four Rules for Predicting the Future is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/34E9Yzr

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment