The Art of Traditional Japanese Wood Joinery: A Kyoto Woodworker Shows How Japanese Carpenters Created Wood Structures Without Nails or Glue

Anyone can develop basic woodworking skills — and, per the advice of Nick Offerman, perhaps everyone should. Those who do learn that things of surprising functionality can be made just by cutting pieces of wood and nailing or gluing them together. Fewer, however, have the patience and dedication to master woodworking without nails or glue, an art that in Japan has been refined over many generations. Traditional Japanese carpenters put up entire buildings using wood alone, cutting the pieces in such a way that they fit together as tightly as if they’d grown that way in the first place. Such unforgiving joinery is surely the truest test of woodworking skill: if you don’t do it perfectly, down comes the temple.

“At the end of the 12th century, fine woodworking skills and knowledge were brought into Japan from China,” writes Yamanashi-based woodworker Dylan Iwakuni. “Over time, these joinery skills were refined and passed down, resulting in the fine wood joineries Japan is known for.”

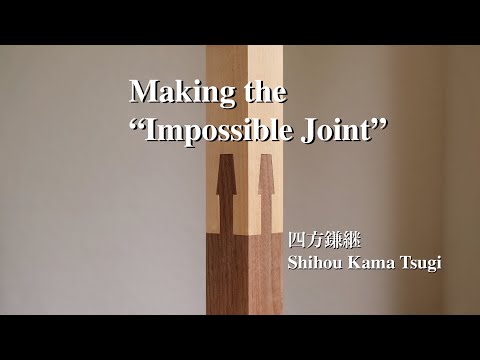

As it became a tradition in Japan, this carpentry developed a canon of joining methods, several of which Iwakuni demonstrates in the video at the top of the post. Can it be a coincidence that these most trustworthy joints — and the others featured on Iwakuni’s joinery playlist, including the seemingly “impossible” shihou kama tsugi — are also so aesthetically pleasing, not just in their creation but their finished appearance?

In addition to his Youtube channel, Iwakuni maintains an Instagram account where he posts photos of joinery not just in the workshop but as employed in the construction and maintenance of real buildings. “Joineries can be used to replace a damaged part,” he writes, “allowing the structure to stand for another hundreds of years.” To do it properly requires not just a painstakingly honed set of skills, but a perpetually sharpened set of tools — in Iwakuni’s case, the visible sharpness of which draws astonished comment from woodworking aficionados around the world. “Blimey,” as one Metafilter user writes, “it’s hard enough getting a knife sharp enough to slice onions.” What an audience Iwakuni could command if he expanded from woodworking Youtube into cooking Youtube, one can only imagine.

Related Content:

See How Traditional Japanese Carpenters Can Build a Whole Building Using No Nails or Screws

Watch Japanese Woodworking Masters Create Elegant & Elaborate Geometric Patterns with Wood

20 Mesmerizing Videos of Japanese Artisans Creating Traditional Handicrafts

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, on Facebook, or on Instagram.

The Art of Traditional Japanese Wood Joinery: A Kyoto Woodworker Shows How Japanese Carpenters Created Wood Structures Without Nails or Glue is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/39ZR09C

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment