How Martin Luther King Jr. Went from Getting C’s on His Report Card (Even in Public Speaking) to Straight A’s

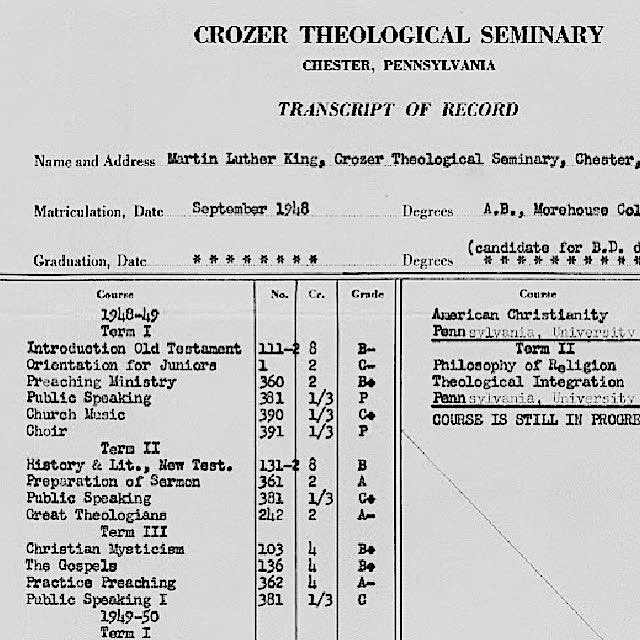

How many Americans have never heard the name of Martin Luther King Jr.? And indeed, gone more than half a century though he may be, how many Americans have never heard his voice, or can’t quote his words? Long though King will doubtless stand as an example of the English language’s greatest 20th-century orators, he once showed scant academic promise in that department. Tweeting out an image of his transcript from Crozer Theological Seminary, where King earned his Bachelor of Divinity, Harvard’s Sarah Elizabeth Lewis notes that King “received two Cs in public speaking,” and “actually went from a C+ to a C the next term.”

Still, that beat the marks King had previously received at Morehouse College. In an article for The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education, Stanford’s Clayborne Carson quotes religion professor George D. Kelsey as describing King’s record there as “short of what may be called ‘good,'” but also adding that King came “to realize the value of scholarship late in his college career.” This early underachievement may have been a consequence of King’s entrance into college at the young age of fifteen, which was made possible by Morehouse’s offering its entrance exam to junior high schoolers, its student body having been depleted by enlistment in the Second World War.

But King “probably realized that he would have to become more diligent in his studies if he were to succeed at the small Baptist institution in Chester, Pennsylvania, a small town southwest of Philadelphia,” writes Carson. “Evidently wishing to break with the relaxed attitude he had had toward his Morehouse studies,” he “quickly immersed himself in Crozer’s intellectual environment” and adopted a mien of high seriousness. “If I were a minute late to class, I was almost morbidly conscious of it,” King later recalled. “I had a tendency to overdress, to keep my room spotless, my shoes perfectly shined, and my clothes immaculately pressed.”

The young King eventually rose to the role in which he’d cast himself, thanks in part to the rigor of certain professors who knew what to expect from him. Apart from the sole minus blemishing his grade in “Christianity and Society,” his transcript for 1950-51 shows straight As. “By the time of his graduation,” Carson writes, “King’s intellectual confidence was reinforced by the experience of having successfully competed with white students during his Crozer years.” Named student body president and class valedictorian, “he was also accepted for doctoral study at Boston University’s School of Theology, where he would be able to work directly with the personalist theologians he had come to admire.” Even then, one suspects, King knew the real work lay ahead of him — and well outside the academy, at that.

Related Content:

How Martin Luther King, Jr. Used Nietzsche, Hegel & Kant to Overturn Segregation in America

Albert Einstein’s Grades: A Fascinating Look at His Report Cards

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, on Facebook, or on Instagram.

How Martin Luther King Jr. Went from Getting C’s on His Report Card (Even in Public Speaking) to Straight A’s is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/2X8Tlrv

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment