What is a Blade Runner? How Ridley Scott’s Movie Has Origins in William S. Burroughs’ Novella, Blade Runner: A Movie

Why, in the course of two extraordinary films by Ridley Scott and Denis Villeneuve, do we never learn what the term Blade Runner actually means? Perhaps the mystery only deepens the sense of “super-realism” with which the film leaves audiences, including—and especially—Philip K. Dick, who only lived long enough to see excerpts. “The impact of Blade Runner is simply going to be overwhelming, both on the public and on creative people,” he wrote. As usual, Dick saw beyond his contemporaries, who mostly panned or ignored the film.

Dick seemed to have “had no beef with the fact Blade Runner was not a faithful adaptation of his novel,” writes David Barnett at the Independent. Not only did he not write a book called Blade Runner—the film was loosely adapted from his 1968 book Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?—but he also never used those words, "Blade Runner," to describe his characters. “It’s not a phrase used in the book and it doesn’t really make much sense in the context of the movie…. It’s simply a throwaway slang for cops who hunt replicants.”

The phrase, as Keele University professor Oliver Harris tells The Quietus, is so much more than that. It brings along with it “a weird backstory that tells us something about how the Burroughs virus spreads around,” infecting nearly everything science fictional and countercultural over the past half-century or so. That’s William S. Burroughs, of course, author of—among a few other things—a 1979 novelistic film treatment called Blade Runner: A Movie.

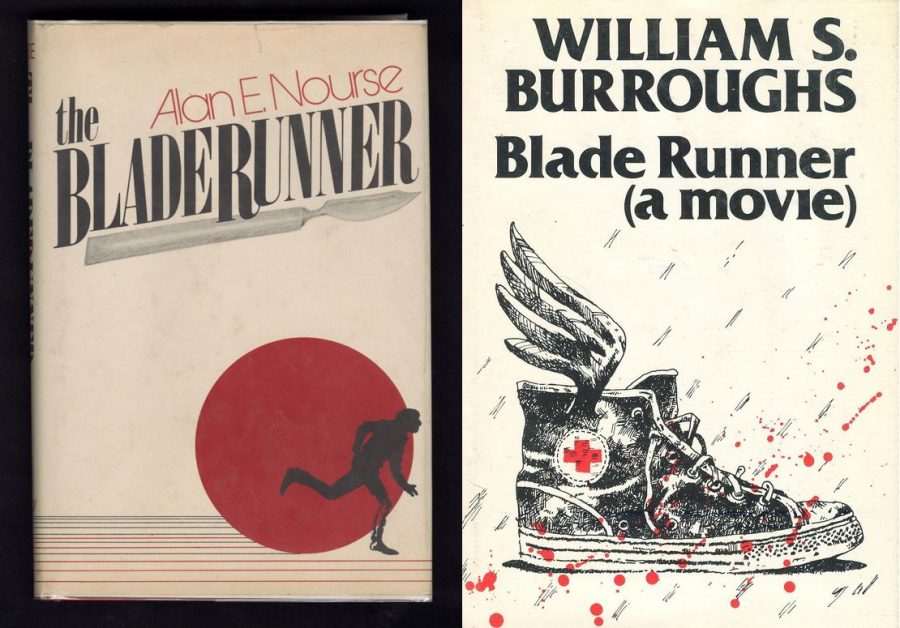

If Scott and screenwriter Hampton Fancher had adapted Burroughs’ nightmarish 21st century to the cinema, we would have seen a much different film—though one as wholly resonant with our current dystopia. The story imagines “a medical-care apocalypse,” in which medical supplies like scalpels become smuggled contraband—hence “blade runners.” Burroughs' book is itself an adaptation—or a re-writing and re-editing—of sci-fi writer Alan Nourse’s 1974 pulp sci-fi novel The Bladerunner.

It is Nourse who introduced the scenario of a “medical apocalypse” and who coined the term “blade runner,” though we owe its separation into two words to Burroughs. “Reading one text against the other is fascinating,” says Harris. “Nourse writes pedestrian, realist prose with two-dimensional characters who all talk in the same colourless style.” Burroughs, on the other hand, writes with “extraordinary economy, mastery of idiom, and wildly unbound imagination.”

In the crumbling New York (not L.A.) of Burroughs’ future world, the government controls its citizens “through the ability to withhold essential services including work, credit, housing, retirement benefits and medical care through computerization.” Granted, this might not seem to lend itself to a very cinematic treatment, but Burroughs was attracted to the central concept of Nourse’s book, one inherently rich in human tragedy: “medical pandemics appealed to his vision of a species in peril, a planet heading for terminal disaster.”

Dick imagined a species in peril from a different kind of infection, as Burroughs would have it—artificial intelligence. Was the most cinematically-adapted sci-fi novelist aware that he had indirectly helped reintroduce a strain of the Burroughs virus—a paranoid, if justified, suspicion of authority—back into popular culture through Blade Runner? We might expect, given his status in the science fiction community at the time of his death, three months before the film debuted, that he might be aware of the connection. But he gave no hint of it, leaving us to ponder what Burroughs' Blade Runner: The Movie, the movie, would be like, made with the skill and sensibility of a Scott or Villeneuve.

Related Content:

How Blade Runner Captured the Imagination of a Generation of Electronic Musicians

Philip K. Dick Previews Blade Runner: “The Impact of the Film is Going to be Overwhelming” (1981)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

What is a Blade Runner? How Ridley Scott’s Movie Has Origins in William S. Burroughs’ Novella, Blade Runner: A Movie is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/2OryQ50

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment