“The search for authentic Mexican food—or rather, the struggle to define what that meant—has been going on for two hundred years,” writes Jeffrey Pilcher at Guernica. Arguments over national cuisine first divided into factions along historical lines of conquest. Indigenous, corn-based cuisines were pitted against wheat-based European foods, while Tex-Mex cooking has been “industrialized and carried around the world,” its processed commodification posing an offense to both indigenous peoples and Spanish elites, who themselves later “sought to ground their national cuisine in the pre-Hispanic past” in order to fend off associations with globalized Mexican food of the chain restaurant variety.

Stephanie Noell, Special Collections Librarian at the University of Texas San Antonio (UTSA), explains how these lines were drawn centuries earlier during the “culinary cultural exchange” of the colonial period: “[C]onquistador Bernal Diaz del Castillo referred to corn dishes as the ‘misery of maize cakes.’ On the other side, the Nahuas were not impressed by the Spaniards’ wheat bread, describing it as ‘famine food.’” Whatever we point to—corn, wheat, etc.—and call “Mexican food,” we are sure to be corrected by someone in the know.

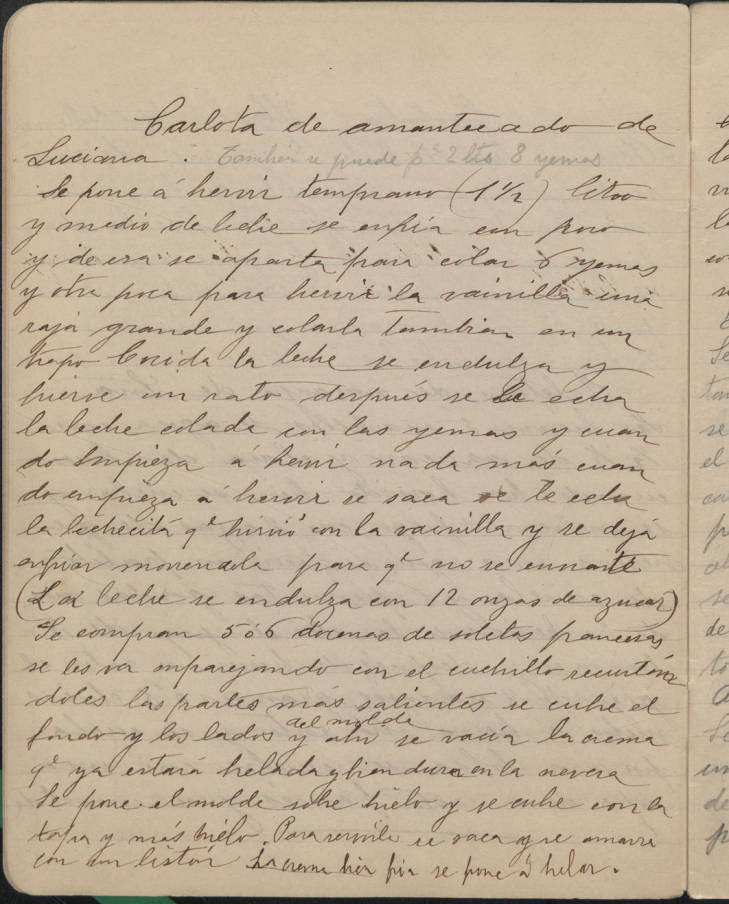

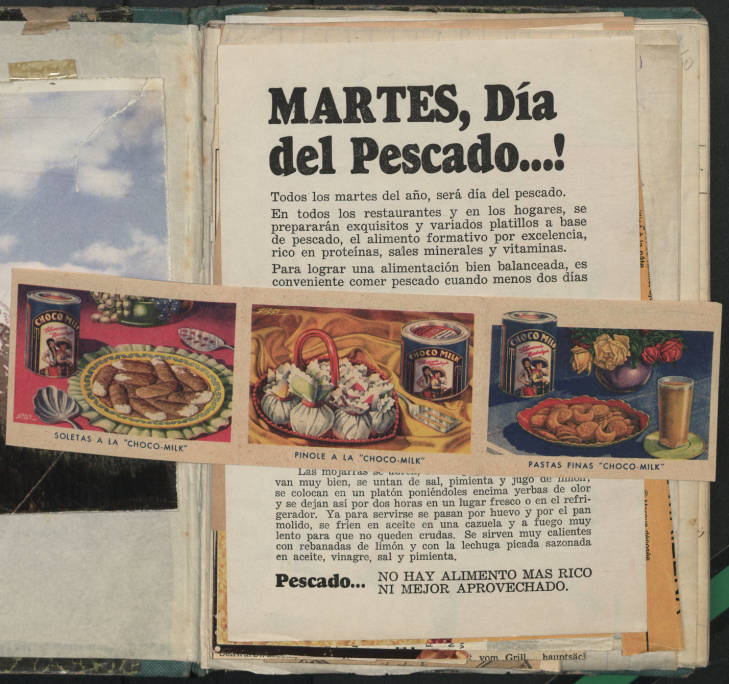

Cooking, as everyone knows, is not only regional and political, but also deeply personal-- tied to family gatherings and passed through generations in handwritten recipes, sometimes jealously guarded lest they be stolen and turned into fast food. But thanks to UTSA Libraries, we have access to hundreds of such recipes. An initial donation of 550 cookbooks has grown to include “over 2,000 titles in English and Spanish,” notes UTSA, “documenting the history of Mexican cuisine from 1789 to the present, with most books dating from 1940-2000.” Many of the books, like that below from 1960, consist of handwritten content next to cut-and-paste recipes and ideas from magazines.

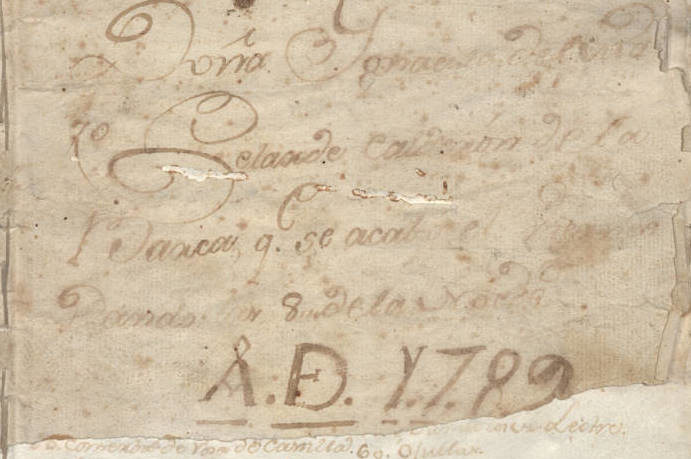

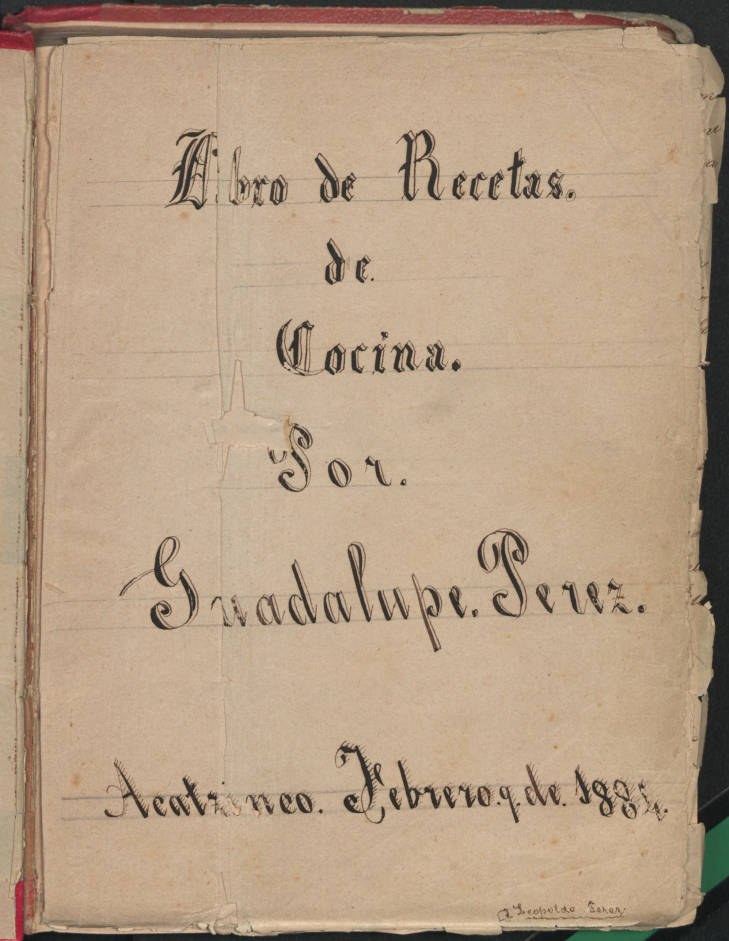

The collection spans “regional cooking, healthy and vegetarian recipes, corporate advertising cookbooks, and manuscript recipe books.” The oldest cookbook, belonging to someone named “Doña Ignacita,” whom Noell believes to have been the kitchen manager of a wealthy family, “is a handwritten recipe collection in a notebook,” writes Nils Bernstein at Atlas Obscura, “complete with liquid stains, doodles, and pages that naturally fall open to the most-loved recipes.” Like the other manuscript cookbooks in the collection, “never intended for public scrutiny,” this one “provides essential insight on how real households cooked on a regular basis.”

“I’ve had students in tears going through these,” says Noell, “because it’s so powerful to see that connection with how their family makes certain dishes and where they originated.” On the other hand, we also have generic “Corporate Cookbooks” like Recetario Bimbo, a book of sandwich recipes from the well-known bread company Bimbo. Recent publications like the ultra-hip, 2017 Fiesta: Vegan Mexican Cookbook, which promises “over 75 authentic vegan-Mexican food recipes included,” strain the word “authentic” to its breaking point. (“Want to feel all the great benefits from the ketogenic diet?” the book’s blurb asks, a question that probably never occurred to either Aztecs or Conquistadors.)

The UTSA Mexican Cookbooks collection is open to the public and anyone can visit it in person, but Noell wants “anybody with an internet connection to be able to see these works.” UTSA has been busy digitizing the 100 manuscript cookbooks in the collection, and has scanned about half so far, with Doña Ignacita’s 1789 notebook coming soon. While these aren’t likely to resolve debates about what constitutes authentic Mexican cooking—as if such a thing existed in a monolithic, timeless form—they are sure to be of very keen interest to chefs, home cooks, historians, and enthusiasts of the history of Mexican food. Enter the digital collection of manuscript cookbooks here.

Related Content:

An Archive of 3,000 Vintage Cookbooks Lets You Travel Back Through Culinary Time

The Futurist Cookbook (1930) Tried to Turn Italian Cuisine into Modern Art

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

An Archive of Handwritten Traditional Mexican Cookbooks Is Now Online is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/38mmnru

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment