A new Partially Examined Life interview with Judith Butler, Maxine Elliot Professor of Comparative Literature at UC Berkeley, discusses the ethics and psychology of nonviolence. This follows a three-part treatment on the podcast of her earlier work.

For a first-hand account of her new book, you can watch two 2016 lectures that she gave at UC Berkeley on early versions of the text:

Watch on YouTube. Watch the second lecture.

Butler has been a tremendously influential (and controversial) figure in ongoing intellectual debates about gender and sexuality. Her 1990 book Gender Trouble argues that gender is a "performance," i.e. a habitual group of behaviors that reflect and reinforce social gender norms. Practices such as dressing in drag satirize this performance, showing how even in "normal" situations, "acting feminine" is not a reflection of one's inner essence but is a matter of putting on a display of culturally expected mannerisms. The drag performer (on Butler's analysis) may convey an absurdity that deconstructs the expected accord of biological sex, sexual preference, and gender identity: "I'm dressing like a woman but am really a man; also, in my everyday life, I dress like a man but am really (in the way I actually feel about myself) am a woman." Most controversially, as a post-structuralist, Butler argues that it's not the case that there is an uncontroversial biological fact of sex that then culture connects gender behaviors to. Instead, all of our understanding of the so-called biological fact comes through the cultural lens of gender; we literally can't understand any such raw, biological fact apart from its cultural associations. In other words, it's not just gender that's a social construction, but biological sex itself.

This position has been attacked both from the position of naive, common-sense scientism (of course biological differences resulting in babies isn't just a matter of what concepts a particular society has happened to develop) and as a moral hazard and existential threat: In 2017 while at a conference in Brazil, far-right Christian groups protested her presence and even burned her in effigy.

It should also be noted that Butler's take on gender departs from current, intuitive explanations of the phenomena of transgenderism, i.e. that one might feel their "true gender" to be different from what society has assigned them. For Butler, there is no inner gender essence that may or may not be displayed authentically. Instead, the "inner" is a cultural construction, itself built out of our external performances and the dynamics of our psychic life, which she discusses within the psychoanalytic tradition.

This use of psychoanalysis to explain our cultural life persists in newly released book, The Force of Nonviolence: An Ethico-Political Bind. Though the theory of nonviolent political protest may seem a far-flung topic from gender studies, both involve the process of defining an identity. In the case of gender, one defines oneself as a particular gender or as being of a particular sexual orientation (as opposed to leaving these attributes ambiguous and fluid) by grasping onto a strict social division between the available sexual options and declaring that one of them is "not me." In Butler's discussion of nonviolence, she instead focuses on what counts as "self" in the usually excused exception to nonviolence, self-defense. She's criticizing a position where most of us claim to be nonviolent (and claim that our government is nonviolent) because we are not the aggressors: We will fight only when we are attacked or threatened.

It's not that Butler is categorically against using violence to defend oneself, one's loved ones, one's country, or anyone else who is in danger of being seriously harmed. She is, however, arguing for an ethic of nonviolence that clearly understands our interrelatedness with everyone else in the world, even and especially those that we might think outside our circle of concern. It's too easy for us to define "self" as "people like us," which then leaves out the rest of the populace (and the non-human population, and the environment more generally) from inclusion in our "self-defense" calculations of when violence might be justified. Butler analyzes the fear of immigrants, for instance, as a "phantasmatic transmutation" that projects the potential for violence that always exists within our immediate social relations (and even our own rage against ourselves) onto an invading Other. As in the case of gender, she wants us instead to understand the dynamics of these self-and-other attributions, to behave more rationally and humanely, and to channel our unavoidable rage constructively into forceful non-violence, or what Gandhi calls Satyagraha, "polite insistence on the truth." The goal of this type of political action is conversion, not coercion, and it's communication and respecting even a hated other as a grievable equal that provides a real contrast to violence. She wants us to recognize the potential for violence within each relationship, at each moment, and to choose otherwise.

The Partially Examined Life Philosophy Podcast began a discussion of the general concept of social construction back with in Ocotober with episode 227, following this up with applications of this concept to race (discussing Kwame Anthony Appiah and Charles Mills with in episode 228 with guest Coleman Hughes), to the development of science (considering Bruno Latour on episode 230 with guest Professor Lynda Olman), and to gender (considering Simone de Beauvoir's The Second Sex for episode 232 with Professor Jennifer Hansen. Professor Hansen then continued with hosts Mark Linsenmayer, Wes Alwan, Seth Paskin, and Dylan Casey to discuss Butler's Gender Trouble. For further explanation of The Force of Nonviolence, see episode 236 at partiallyexaminedlife.com.

Mark Linsenmayer is the host of the Partially Examined Life, Pretty Much Pop, and Nakedly Examined Music podcasts. He is a writer and musician working out of Madison, Wisconsin. Read more Open Culture posts about The Partially Examined Life.

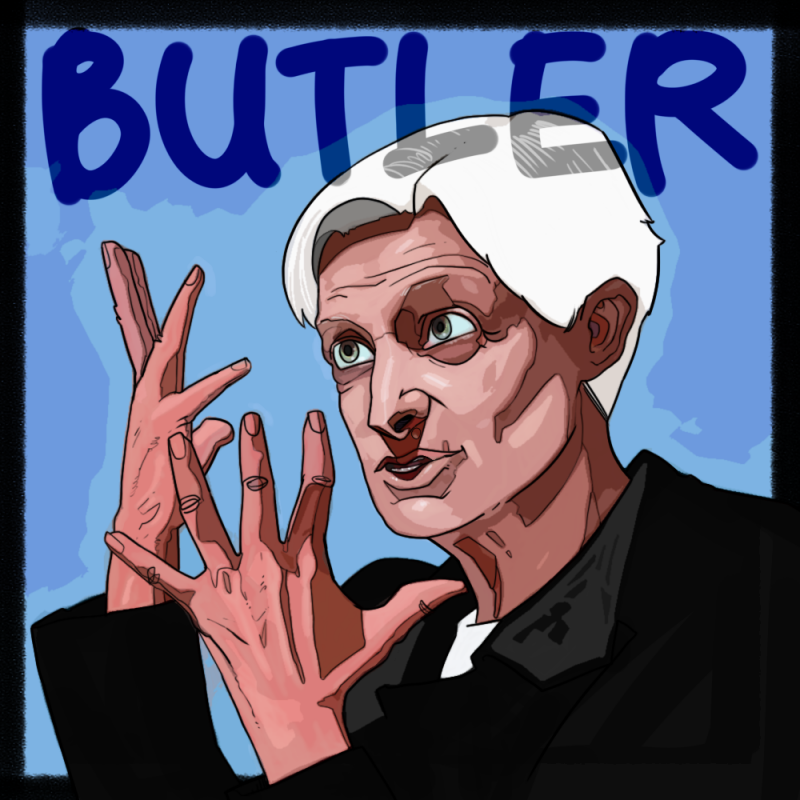

Image by Solomon Grundy.

Judith Butler on Nonviolence and Gender: Hear Conversation with The Partially Examined Life is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/38ZAXFv

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment