Free: Read the Original 23,000-Word Essay That Became Hunter S. Thompson’s Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas (1971)

Because my story was true. I was certain of that. And it was extremely important, I felt, for the meaning of our journey to be made absolutely clear.

The publication history of Hunter S. Thompson’s Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas is the story of gonzo journalism itself, a form dependent upon the unreliability of its narrator, who becomes a central character in the ostensibly real-life drama. In Thompson’s hallucinogenic tales of his travels to Las Vegas with attorney and Chicano activist Oscar Zeta Acosta, the reporter went so far as to become a fictional character.

The journey began with a commission from Rolling Stone to report on the death of reporter Ruben Salazar, killed by a Los Angeles police tear gas grenade at an anti-Vietnam War protest. This trip diverted, however, to Las Vegas, where Thompson drove to report on the Mint 400 desert race for Sports Illustrated. Rather than submitting the 250-word piece the magazine requested, he gave them a 2,500-word psychedelic fugue, the very beginnings of Fear and Loathing. The piece, Thompson later wrote, was “aggressively rejected.”

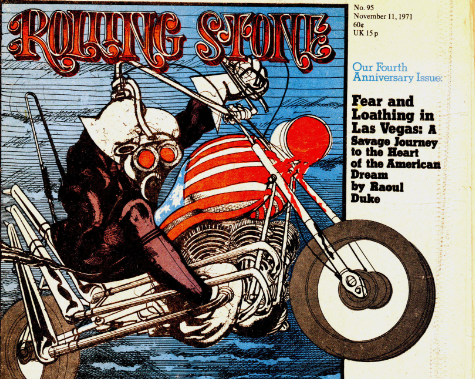

Instead, Jann Wenner liked what he saw enough to eventually publish it in the November 1971 issue of Rolling Stone as a 23,000-word essay bearing the title of the novel it would become, “Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas: A Savage Journey to the Heart of the American Dream.” You can read that by-now familiarly wild account, here. In it, Thompson gave the magazine’s readers a succinct definition of his reporting style:

But what was the story? Nobody had bothered to say. So we would have to drum it up on our own. Free Enterprise. The American Dream. Horatio Alger gone mad on drugs in Las Vegas. Do it now: pure Gonzo journalism.

The term defines the form as the mirror obverse of the American Dream, Thompson’s excesses no more than illicit versions of the culture he picked apart, one that produced an event like the Mint 400, “the richest off-the-road race for motorcycles and dune-buggies in the history of organized sport," he wrote, and "a fantastic spectacle….”

What were Thompson and Acosta (or Raoul Duke and Dr. Gonzo) doing if not holding the main event of disorganized sport in their race across the desert against their own paranoid delusions? The truths Thompson told need never have been factual—they were the outrageous truths we find in any good story, well told: about the bats—as in the famous Goya etching—swarming around the passed-out head of Reason.

Read Thompson's original, now iconic essay here.

Related Content:

Read 11 Free Articles by Hunter S. Thompson That Span His Gonzo Journalist Career (1965-2005)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Free: Read the Original 23,000-Word Essay That Became Hunter S. Thompson’s Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas (1971) is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/3ab3mZx

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment