Jules Verne’s Most Famous Books Were Part of a 54-Volume Masterpiece, Featuring 4,000 Illustrations: See Them Online

Not many readers of the 21st century seek out the work of popular writers of the 19th century, but when they do, they often seek out the work of Jules Verne. Journey to the Center of the Earth, Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, Around the World in Eighty Days: fair to say that we all know the titles of these fantastical French tales from the 1860s and 70s, and more than a few of us have actually read them. But how many of us know that they all belong to a single series, the 54-volume Voyages Extraordinaires, that Verne published from 1863 until the end of his life? Verne described the project's goal to an interviewer thus: "to conclude in story form my whole survey of the world’s surface and the heavens."

Verne intended to educate, but at the same time to entertain and even artistically impress: "My object has been to depict the earth, and not the earth alone, but the universe," he said. "And I have tried at the same time to realize a very high ideal of beauty of style." This he accomplished with great success in a time and place without even what we would now consider a fully literate public.

As philosopher Marc Soriano writes of the 1860s when Verne began publishing, "The drive for literacy in France has been underway since the Guizot Law of 1833, but there is still much to do. Any well-advised editor must aid his readers who have not yet achieved a good reading proficiency."

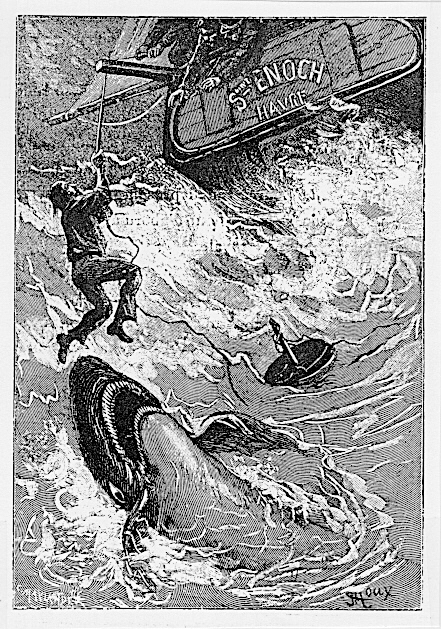

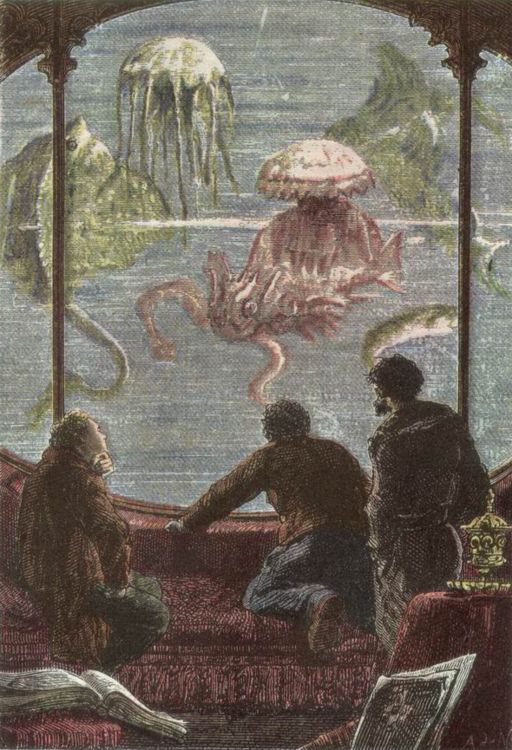

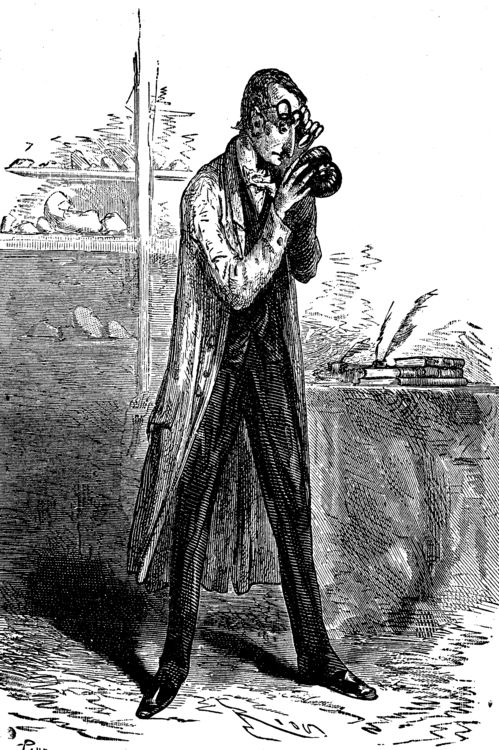

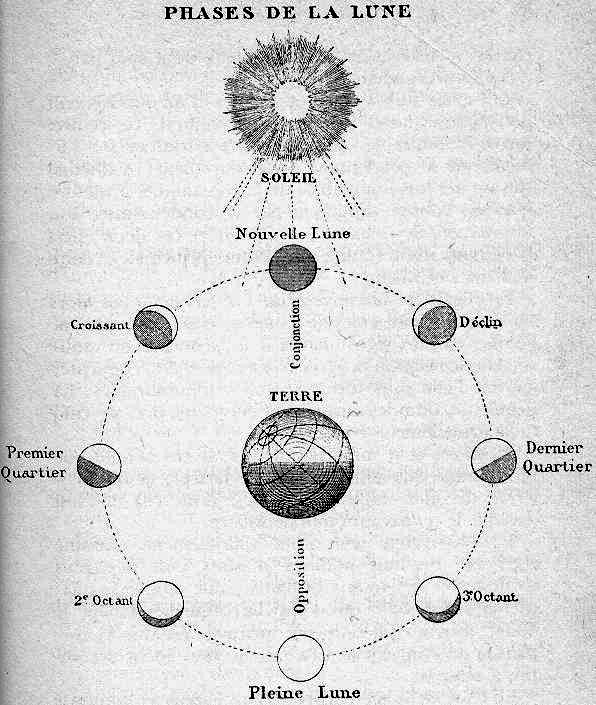

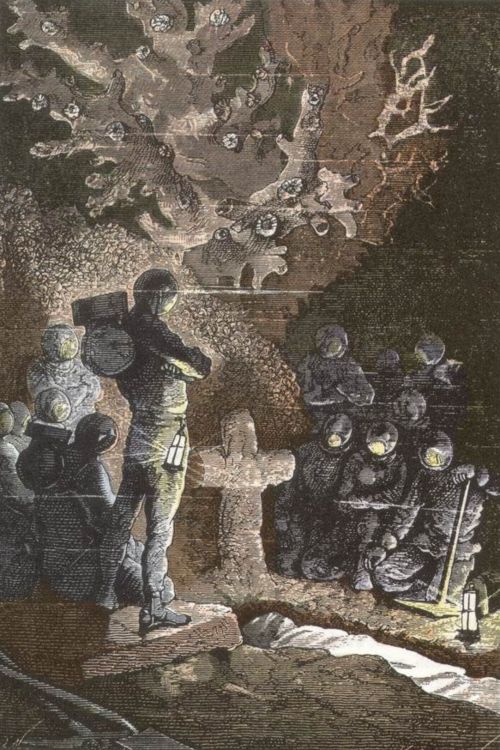

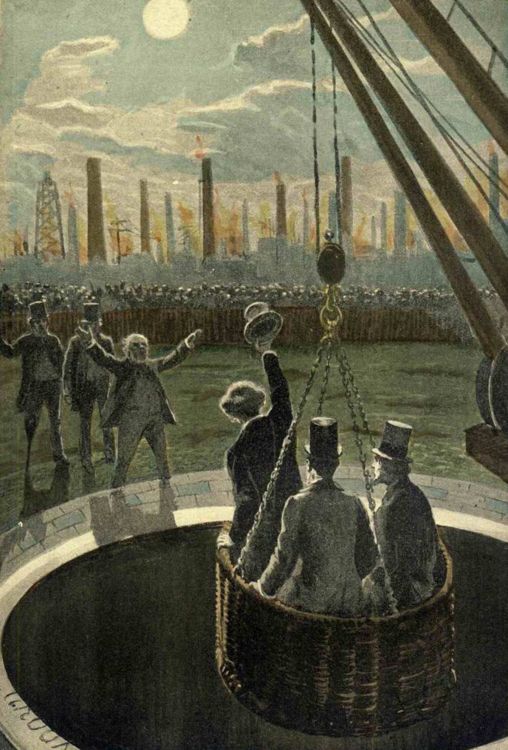

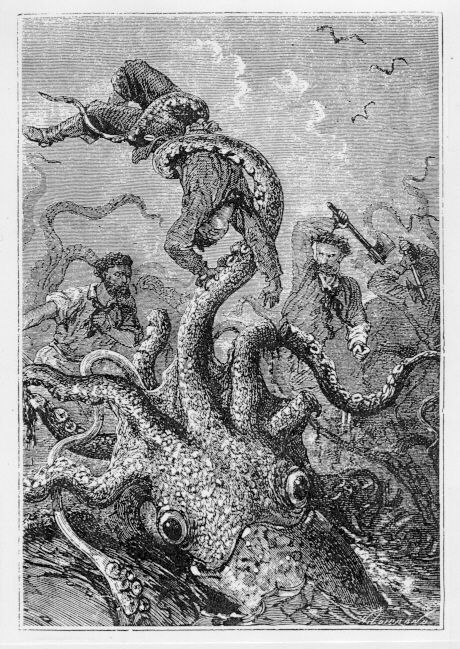

Hence the need for illustrations: beautiful illustrations, scientifically and narratively faithful illustrations, and above all a great many illustrations: over 4,000 of them, by the count of Arthur B. Evans in his essay on the series' artists, "an average of 60+ illustrations per novel, one for every 6-8 pages of text." Still today, "most modern French reprints of the Voyages Extraordinaires continue to feature their original illustrations — recapturing the 'feel' of Verne’s socio-historical milieu and evoking that sense of faraway exoticism and futuristic awe which the original readers once experienced from these texts. And yet, to date, the bulk of Vernian criticism has virtually ignored the crucial role played by these illustrations in Verne’s oeuvre."

Evans identifies four different types of illustrations in the series: "renderings of the protagonists of the story — e.g., portraits like the one of Impey Barbicane in De la terre à la lune"; "panoramic and postcard-like" views of the "exotic locales, unusual sights, and flora and fauna which the heroes encounter during their journey, like the one from Vingt mille lieues sous les mers depicting divers walking on the ocean floor"; "documentational" illustrations like "the map of the Polar regions (hand-drawn by Verne himself) for his 1864 novel Les Voyages et aventures du capitaine Hatteras"; and portayals of "a specific moment of action in the narrative—e.g., the one from Voyage au centre de la terre where Prof. Lidenbrock, Axel, and Hans are suddenly caught in a lightning storm on a subterranean ocean."

Verne and his editor Pierre-Jules Hetzel commissioned these illustrations from no fewer than eight artists, a group including Edouard Riou, Alphonse de Neuville, Emile-Antoine Bayard (previously featured here on Open Culture), and Léon Benett — all well-known artists in late 19th-century France, and made even more so by their work in the Voyages Extraordinaires. You can browse a complete gallery of the series' original illustrations here, and if you like, enrich the experience with this extensive essay by Terry Harpold on "reading" these images in context.

Together with the stories themselves, on the back of which Verne remains the most translated science-fiction author of all time, they allow Harpold to make the credible claim that "the textual-graphic domain constituted by these objects is unmatched in its breadth and variety; no other corpus associated with a single author is comparable." Human knowledge of the universe has widened and deepened since Verne's day, but for sheer intellectual and adventurous wonder about what that universe might contain, has any writer, from any era or land, outdone him since?

Related Content:

How French Artists in 1899 Envisioned Life in the Year 2000: Drawing the Future

Petite Planète: Discover Chris Marker’s Influential 1950s Travel Photobook Series

The Art of Sci-Fi Book Covers: From the Fantastical 1920s to the Psychedelic 1960s & Beyond

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Jules Verne’s Most Famous Books Were Part of a 54-Volume Masterpiece, Featuring 4,000 Illustrations: See Them Online is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/2UCTpiS

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment