The Most Complete Collection of Salvador Dalí’s Paintings Published in a Beautiful New Book by Taschen: Includes Never-Seen-Before Works

Salvador Dali was that rare avant-garde artist whose work earned the respect of nearly everyone, even those who hated him personally. George Orwell called Dali a “disgusting human being,” but added “Dali is a draughtsman of very exceptional gifts…. He has fifty times more talent than most of the people who would denounce his morals and jeer at his paintings.”

Walt Disney was very keen to work with Dali. And Dali’s own personal hero and intellectual father figure, Sigmund Freud—no lover of modern art—found the artist’s “undeniable technical mastery” so compelling that he rethought his longstanding negative opinion of Surrealism.

It’s hard to imagine that Orwell, Disney, and Freud would agree on much else, but when it came to Dali, all three saw what is universally apparent: as an artist, he was “not a fraud,” as Orwell grudgingly admitted.

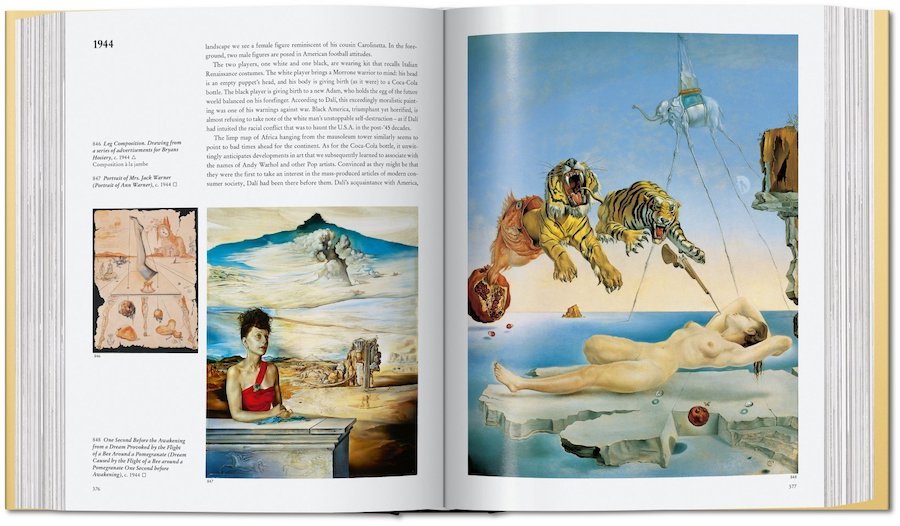

It is also clear that Dali was a “very hard worker.” For all the time he spent in absolutely shameless self-promotion—a full career’s worth of activity for many a current celebrity—Dali still found the time to leave behind hundreds of highly accomplished canvases, drawings, photographs, films, multimedia projects, and more. A trip to the Dali Museum in Tampa, Florida can be a disorienting experience.

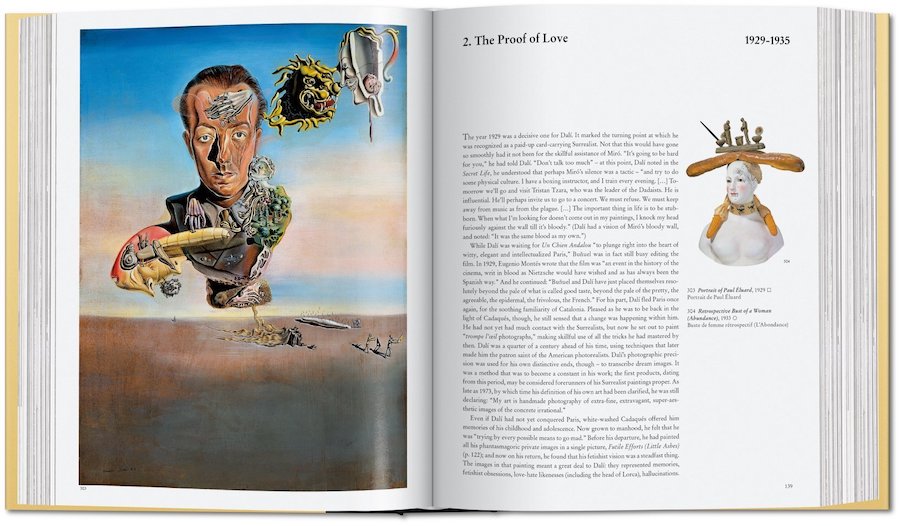

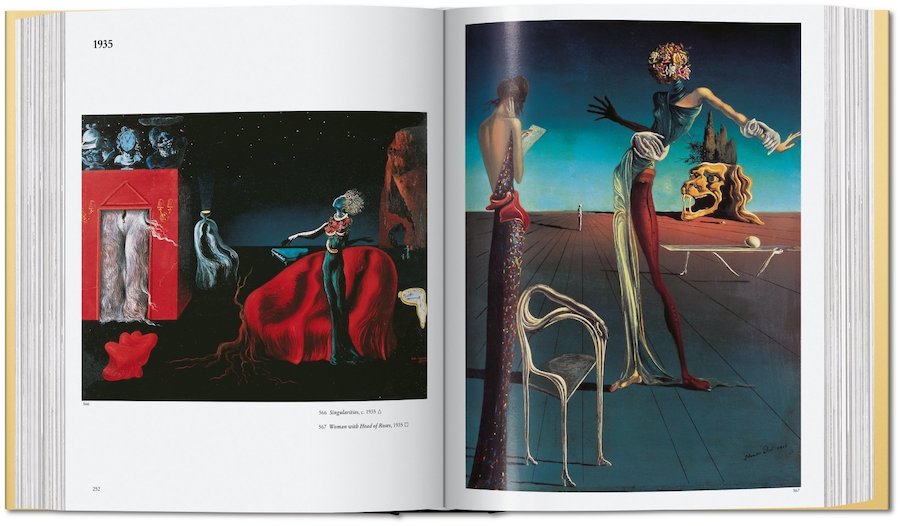

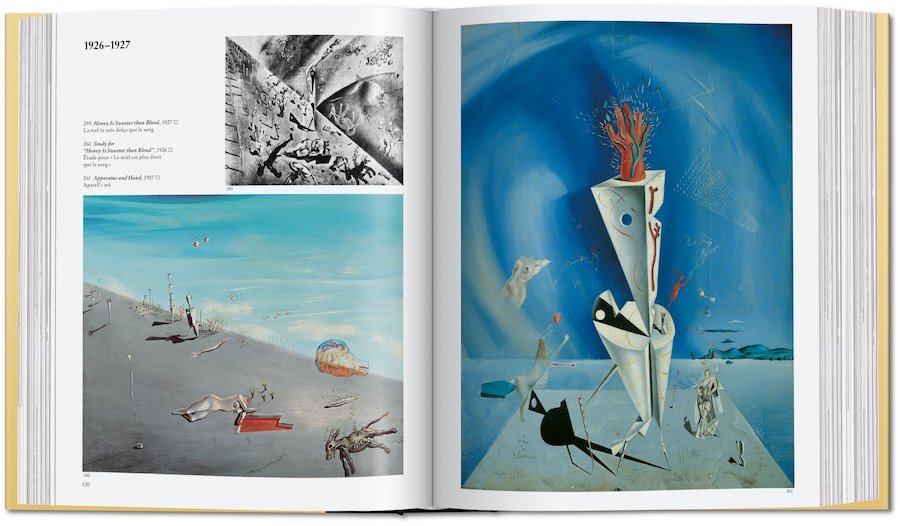

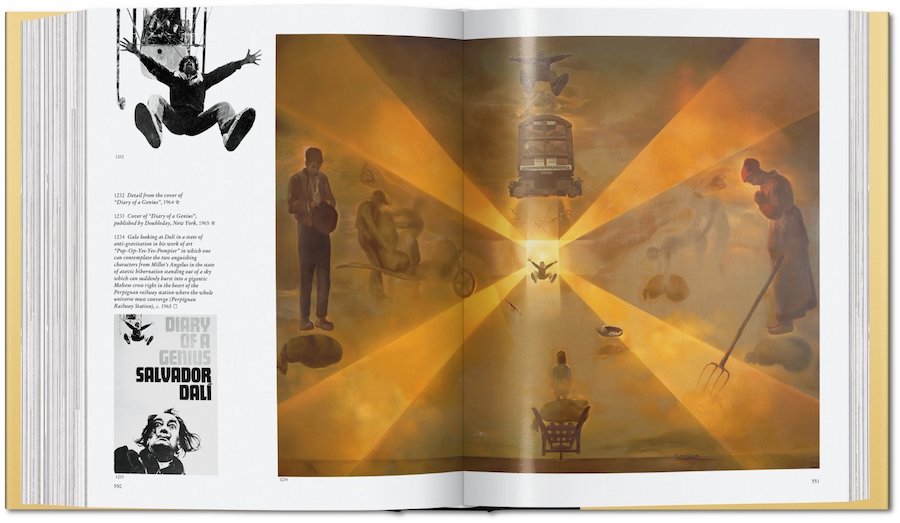

Despite the already sizable body of work we might have seen on view or reproduced, however, the editors of Taschen’s newest, updated edition of Dali: The Paintings have “located painted works by the master that had been inaccessible for years,” as the influential arts publisher notes, “so many, in fact, that almost half the featured illustrations appear in public for the first time.” In addition to the “opulent” presentation of the artwork, the book (which expands on a first edition published last year) also “contextualizes Dali’s oeuvre and its meanings by examining contemporary documents, from writings and drawings to material from other facets of his work, including ballet, cinema, fashion, advertising, and objets d’art.”

The first section of the book reveals how Dali found his own style by mastering everyone else’s. He “deployed all the isms… with playful mastery” and “would borrow from prevailing trends before ridiculing and abandoning them.” Dali wanted us to know that he could have painted anything he wanted, throwing into even higher relief the confounding dream logic of his chosen subjects. Perhaps Dali himself made it impossible—as Orwell had wanted to do—to separate Dali the person from the technical achievements of his art.

As the artist himself saw things, his life and work were all wrapped up together in a singular performance. At the age of seven, he wrote, he had decided he wanted to be Napoleon. “Since then,” Dali mock-humbly confessed, “my ambition has steadily grown, and my megalomania with it. Now I want only to be Salvador Dali, I have no greater wish.” A great part of Dali’s magnetism, of course, is due to what he calls his “megalomania,” or rather to his uncompromising life’s work of becoming fully, completely, himself.

Related Content:

When Salvador Dali Met Sigmund Freud, and Changed Freud’s Mind About Surrealism (1938)

Salvador Dalí’s Tarot Cards Get Re-Issued: The Occult Meets Surrealism in a Classic Tarot Card Deck

Salvador Dalí & Walt Disney’s Short Animated Film, Destino, Set to the Music of Pink Floyd

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

The Most Complete Collection of Salvador Dalí’s Paintings Published in a Beautiful New Book by Taschen: Includes Never-Seen-Before Works is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/394LDlU

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment