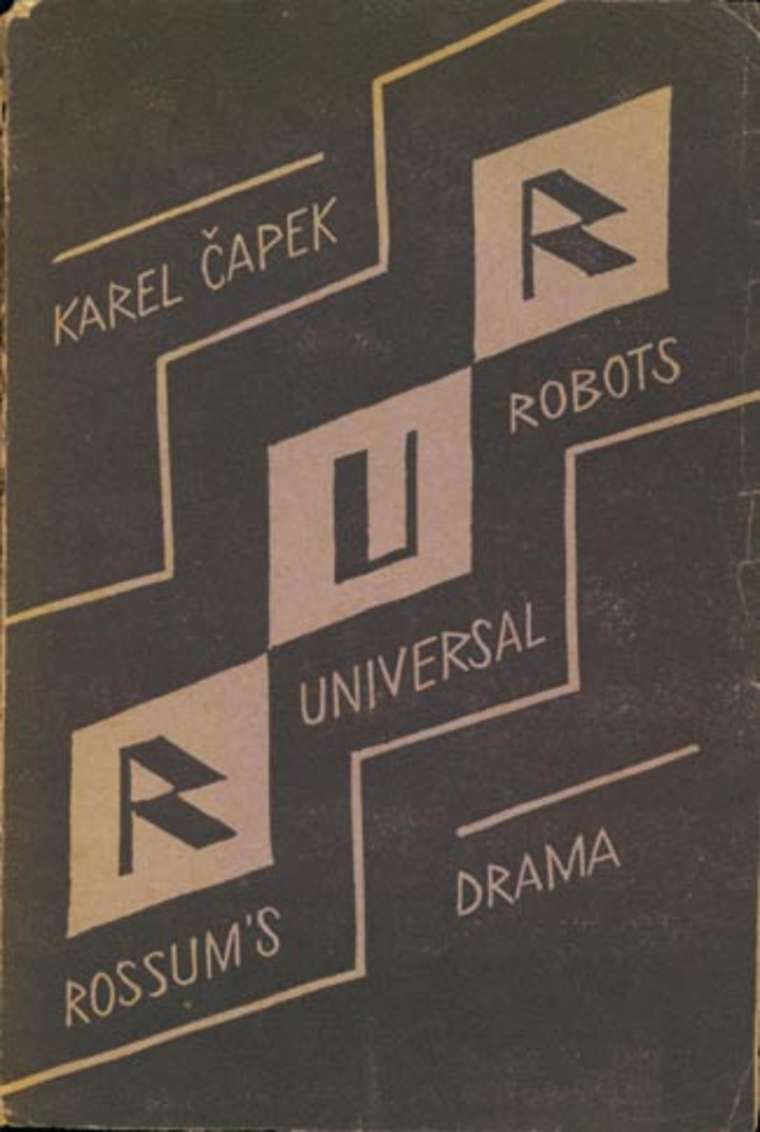

The Word “Robot” Originated in a Czech Play in 1921: Discover Karel Čapek’s Sci-Fi Play R.U.R. (a.k.a. Rossum’s Universal Robots)

When I hear the word robot, I like to imagine Isaac Asimov’s delightfully Yiddish-inflected Brooklynese pronunciation of the word: “ro-butt,” with heavy stress on the first syllable. (A quirk shared by Futurama’s crustacean Doctor Zoidberg.) Asimov warned us that robots could be dangerous and impossible to control. But he also showed young readers—in his Norby series of kids’ books written with his wife Janet—that robots could be heroic companions, saving the solar system from cosmic supervillains.

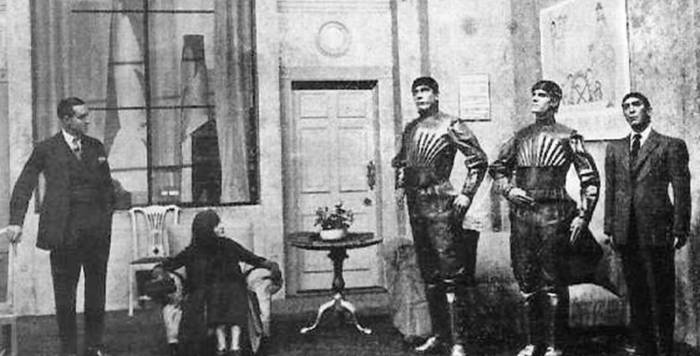

The word robot conjures all of these associations in science fiction: from Blade Runner’s replicants to Star Trek’s Data. We might refer to these particular examples as androids rather than robots, but this confusion is precisely to the point. Our language has forgotten that robots started in sci-fi as more human than human, before they became Asimov-like machines. Like the sci-fi writer’s pronunciation of robot, the word originated in Eastern Europe in 1921, the year after Asimov’s birth, in a play by Czech intellectual Karel ?apek called R.U.R., or “Rossum’s Universal Robots.”

The title refers to the creations of Mr. Rossum, a Frankenstein-like inventor and possible inspiration for Metropolis’s Rotwang (who was himself an inspiration for Dr. Strangelove). ?apek told the London Saturday Review after the play premiered that Rossum was a “typical representative of the scientific materialism of the last [nineteenth] century,” with a “desire to create an artificial man—in the chemical and biological, not mechanical sense.”

Rossum did not wish to play God so much as “to prove God to be unnecessary and absurd.” This was but one stop on “the road to industrial production.” As technology analyst and Penn State professor John M. Jordan writes at the MIT Press Reader, ?apek’s robots were not appliances become sentient, nor trusty, superpowered sidekicks. They were, in fact, invented to be slaves.

The robot… was a critique of mechanization and the ways it can dehumanize people. The word itself derives from the Czech word “robota,” or forced labor, as done by serfs. Its Slavic linguistic root, “rab,” means “slave.” The original word for robots more accurately defines androids, then, in that they were neither metallic nor mechanical.

Jordan describes this history in an excerpt from his book Robots, part of the MIT Press Essential Knowledge Series, and a timelier than ever intervention in the cultural and technological history of robots, who walk (and moonwalk) among us in all sorts of machine forms, if not quite yet in the sense ?apek imagined. But a Blade Runner-like scenario seemed inevitable to him in a society ruled by “utopian notions of science and technology.”

In the time he imagines, he says, "the product of the human brain has escaped the control of human hands.” ?apek has one character, the robot Radius, make the point plainly:

The power of man has fallen. By gaining possession of the factory we have become masters of everything. The period of mankind has passed away. A new world has arisen. … Mankind is no more. Mankind gave us too little life. We wanted more life.

Sound familiar? While R.U.R. owes a “substantial” debt to Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, it’s also clear that ?apek contributed something original to the critique, a vision of a world in which “humans become more like their machines,” writes Jordan. “Humans and robots… are essentially one and the same.” Beyond the surface fears of science and technology, the play that introduced the word robot to the cultural lexicon also introduced the darker social critique in most stories about them: We have reason to fear robots because in creating them, we’ve recreated ourselves; then we've treated them the way we treat each other.

You can find the text of ?apek's play in book format on Amazon.

via Boing Boing

Related Content:

Isaac Asimov Explains His Three Laws of Robots

Twerking, Moonwalking AI Robots–They’re Now Here

The Robots of Your Dystopian Future Are Already Here: Two Chilling Videos Drive It All Home

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

The Word “Robot” Originated in a Czech Play in 1921: Discover Karel ?apek’s Sci-Fi Play R.U.R. (a.k.a. Rossum’s Universal Robots) is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/3b9soJU

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment