The Oldest Book Printed with Movable Type is Not The Gutenberg Bible: Jikji, a Collection of Korean Buddhist Teachings, Predated It By 78 Years and It’s Now Digitized Online

The history of the printed word is full of bibliographic twists and turns, major historical moments, and the significant printing of books now so obscure no one has read them since their publication. Most of us have only the sketchiest notion of how mass-produced printed books came into being—a few scattered dates and names. But every schoolchild can tell you the first book ever printed, and everyone knows the first words of that book: “In the beginning….”

The first Gutenberg Bible, printed in 1454 by Johannes Gutenberg, introduced the world to movable type, history tells us. It is “universally acknowledged as the most important of all printed books,” writes Margaret Leslie Davis, author of the recently published The Lost Gutenberg: The Astounding Story of One Book’s Five-Hundred-Year Odyssey. In 1900, Mark Twain expressed the sentiment in a letter “commenting on the opening of the Gutenberg Museum,” writes M. Sophia Newman at Lithub. “What the world is to-day,” he declared, “good and bad, it owes to Gutenberg. Everything can be traced to this source.”

There is kind of an oversimplified truth in the statement. The printed word (and the printed Bible, at that) did, in large part, determine the course of European history, which, through empire, determined the course of global events after the “Gutenberg revolution.” But there is another story of print entirely independent of book history in Europe, one that also determined world history with the preservation of Buddhist, Chinese dynastic, and Islamic texts. And one that begins “before Johannes Gutenberg was even born,” Newman points out.

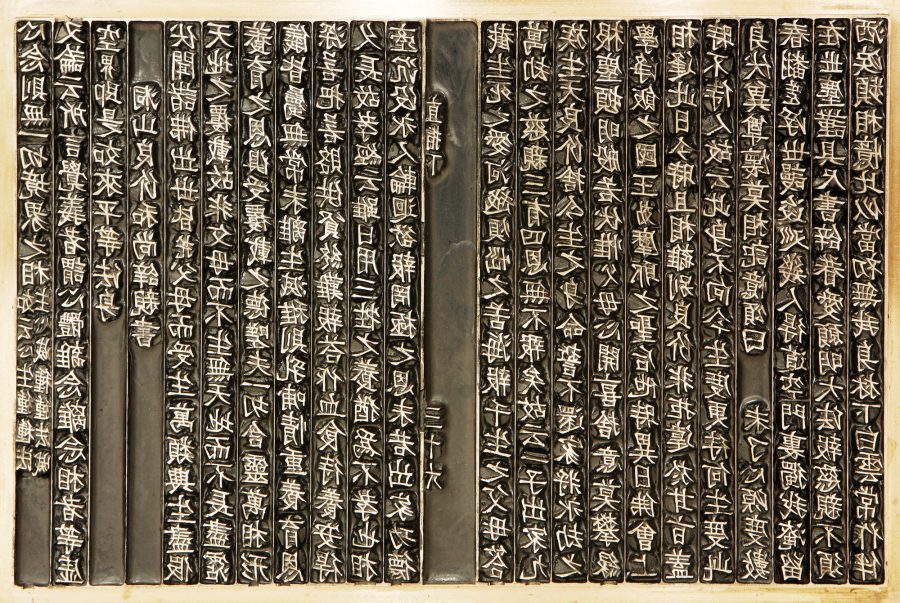

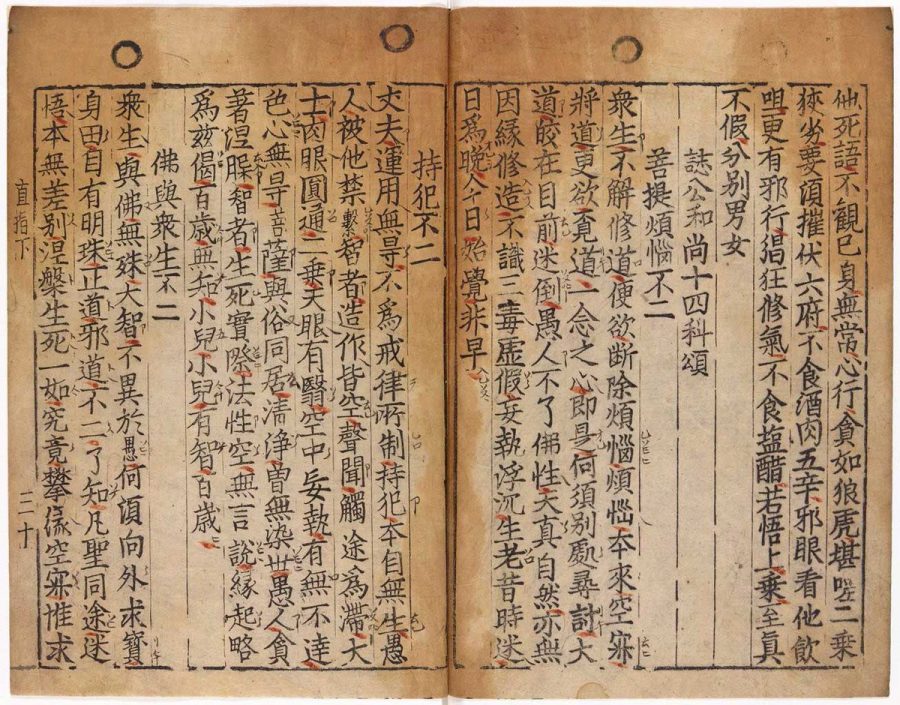

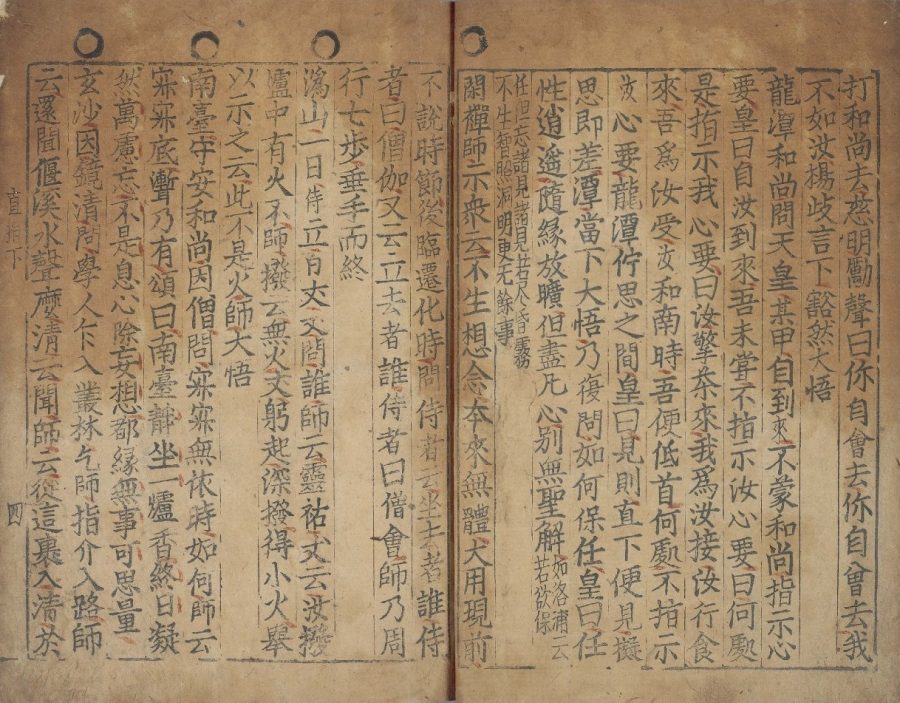

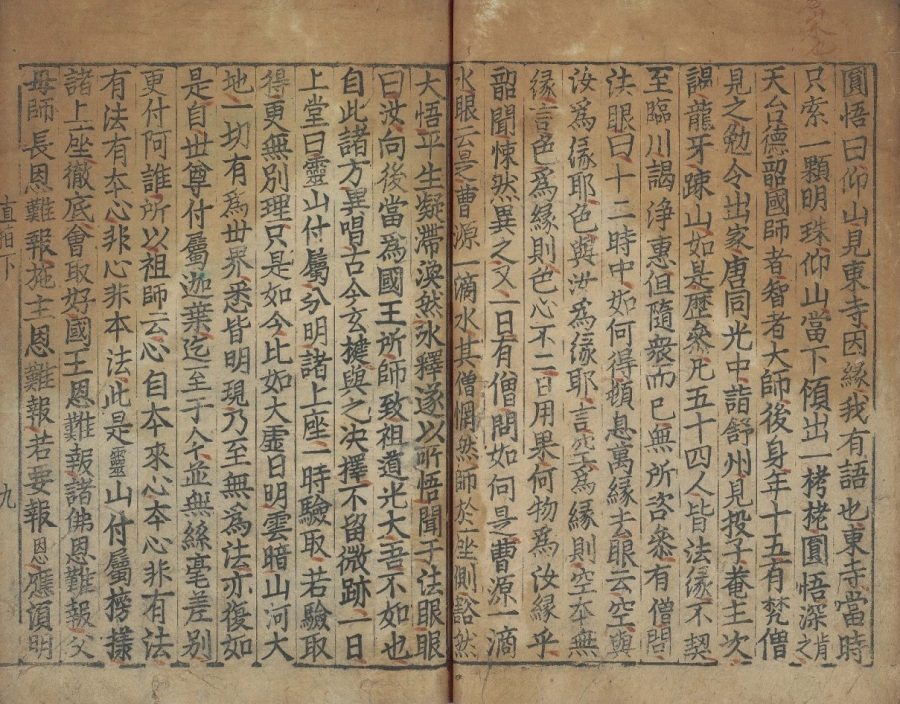

The oldest extant text ever printed with movable type predates Gutenberg himself (born in 1400) by 23 years, and predates the printing of his Bible by 78 years. It is the Jikji, printed in Korea, a collection of Buddhist teachings by Seon master Baegun and printed in movable type by his students Seok-chan and Daijam in 1377. (Seon is a Korean form of Chan or Zen Buddhism.) Only the second volume of the printing has survived, and you can see several images from it here.

Impressive as this may be, the Jikji does not have the honor of being the first book printed with movable type, only the oldest surviving example. The technology could go back two centuries earlier. Margaret Davis nods to this history, Newman concedes, writing that “movable type was an 11th century Chinese invention, refined in Korea in 1230, before meeting conditions in Europe that would allow it to flourish.” This is more than most popular accounts of the printed word say on the matter, but it's still an inaccurate and highly cursory summary of the evidence.

Newman herself says quite a lot more. In essays at Lithub and Tricycle, she describes how printing techniques developed in Asia and were taken up in Korea in the 1200s by the Goryeo dynasty, who commissioned a printer named Choe Yun-ui to reconstruct a woodblock print of the massive collection of ancient Buddhists texts called the Tipitaka after the Mongols burned the only Korean copy. By casting “individual characters in metal” and arranging them in a frame—the same process Gutenberg used—he was able to complete the project by 1250, 200 years before Gutenberg’s press.

This text, however, did not survive, nor did the countless number of others printed when the technology spread across the Mongol empire on the Silk Road and took root with the Muslim Uyghurs. It is possible, though “no clear historical evidence” yet supports the contention, that movable type spread to Europe from Asia along trade routes. “If there was any connection,” wrote Joseph Needham in Science and Civilization in China, “in the spread of printing between Asia and the West, the Uyghurs, who used both block printing and movable type, had good opportunities to play an important role in this introduction.”

Without surviving documentation, this early history of printing in Asia relies on secondary sources. But “the entire history of the printing press" in Europe" is likewise "riddled with gaps,” Newman writes. What we do know is that Jikji, a collection of Korean Zen Buddhist teachings, is the world’s oldest extant book printed with movable type. The myth of Johannes Gutenberg as “a lone genius who transformed human culture,” as Davis writes, “endures because the sweep of what followed is so vast that it feels almost mythic and needs an origin story to match." But this is one inventive individual in the history of printing, not the original, godlike source of movable type.

Gutenberg makes sense as a convenient starting point for the growth and worldwide spread of capitalism and European Christianity. His innovation worked much faster than earlier systems, and others that developed around the same time, in which frames were pressed by hand against the paper. Flows of new capital enabled the rapid spread of his machine across Europe. The achievement of the Gutenberg Bible is not diminished by a fuller history. But "what gets left out” of the usual story, as Newman tells us in great detail, “is startlingly rich.”

“Only very recently, mostly in the last decade” has the long history of printing in Asia been “acknowledged at all” in popular culture, though scholars in both the East and West have long known it. Korea has regarded Jikji "and other ancient volumes as national points of pride that rank among the most important of books.” Yet UNESCO only certified Jikji as the “oldest movable metal type printing evidence” in 2001. The recognition may be late in coming, but it matters a great deal, nonetheless. Learn much more about the history, content, and provenance of Jikji at this site created by “cyber diplomats” in Korea after UNESCO bestowed World Heritage status on the book. And see a fully digitized copy of the book here.

via Lithub

Related Content:

Oxford University Presents the 550-Year-Old Gutenberg Bible in Spectacular, High-Res Detail

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

The Oldest Book Printed with Movable Type is Not The Gutenberg Bible: Jikji, a Collection of Korean Buddhist Teachings, Predated It By 78 Years and It’s Now Digitized Online is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/2xTlLJr

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment