Mister Rogers Creates a Prime Time TV Special to Help Parents Talk to Their Children About the Assassination of Robert F. Kennedy (1968)

Nearly three minutes into a patient blow-by-blow demonstration of how breathing works, Fred Rogers’ timorous hand puppet Daniel Striped Tiger surprises his human pal, Lady Aberlin, with a whammy: What does assassination mean?

Her answer, while not exactly Webster-Merriam accurate, is both considered and age-appropriate. (Daniel's forever-age is somewhere in the neighborhood of four.)

The exchange is part of a special primetime episode of Mister Rogers' Neighborhood, that aired just two days after Senator Robert F. Kennedy’s assassination.

Rogers, alarmed that America’s children were being exposed to unfiltered descriptions and images of the shocking event, had stayed up late to write it, with the goal of helping parents understand some of the emotions their children might be experiencing in the aftermath:

I’ve been terribly concerned about the graphic display of violence which the mass media has been showing recently. And I plead for your protection and support of your young children. There is just so much that a very young child can take without it being overwhelming.

Rogers was careful to note that not all children process scary news in the same way.

To illustrate, he arranged for a variety of responses throughout the Land of Make Believe. One puppet, Lady Elaine, is eager to act out what she has seen: "That man got shot by that other man at least six times!”

Her neighbor, X the Owl, doesn't want any part of what is to him a frightening-sounding game.

And Daniel, who Rogers’ wife Joanne intimated was a reflection "the real Fred,” preferred to put the topic on ice for future discussions—a luxury that the grown up Rogers would not allow himself.

The episode has become notorious, in part because it aired but once on the small screen. (The 8-minute clip at the top of the page is the longest segment we were able to truffle up online.)

Writer and gameshow historian Adam Nedeff watched it in its entirety at the Paley Center for Media, and the detailed impressions he shared with the Neighborhood Archive website provides a sense of the piece as a whole.

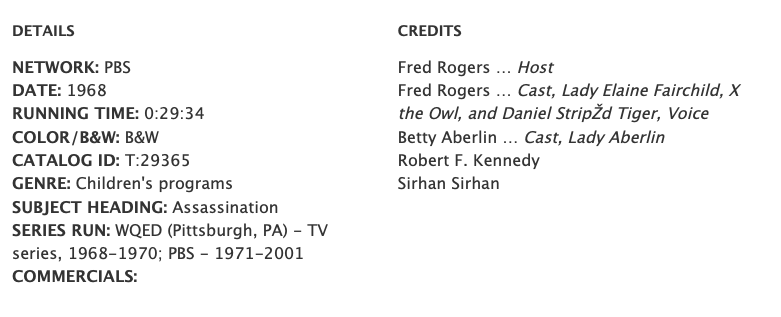

Meanwhile, the Paley Center’s catalogue credits speak to the drama-in-real-life immediacy of the turnaround from conception to airdate:

Above is some of the footage Rogers feared unsuspecting children would be left to process solo. Readers, are there any among you who remember discussing this event with your parents... or children?

Ever vigilant, Rogers returned in the days immediately following the 2001 attack on the World Trade Center, with a special message for parents who had grown up watching him.

Related Content:

Mr. Rogers’ Nine Rules for Speaking to Children (1977)

All 886 episodes of Mister Roger’s Neighborhood Streaming Online (for a Limited Time)

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inkyzine. Join her in NYC on Monday, September 9 for another season of her book-based variety show, Necromancers of the Public Domain. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

Mister Rogers Creates a Prime Time TV Special to Help Parents Talk to Their Children About the Assassination of Robert F. Kennedy (1968) is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/2MehV63

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment