Headaches number among humanity's most common ailments. The headache-related disorders known as migraines may be rarer, afflicting roughly fifteen percent of the population, but they're also much more severe. Besides a headache that can last as long as three days, migraines can also come with various other symptoms including nausea as well as sensitivity to light, sound, and smells. They even cause some sufferers to hallucinate: the visual elements of these pre-migraine "auras" might take the shape of distortions, vibrations, zig-zag lines, bright lights, blobs, or blind spots. Sometimes they also come in color, and brilliant color at that.

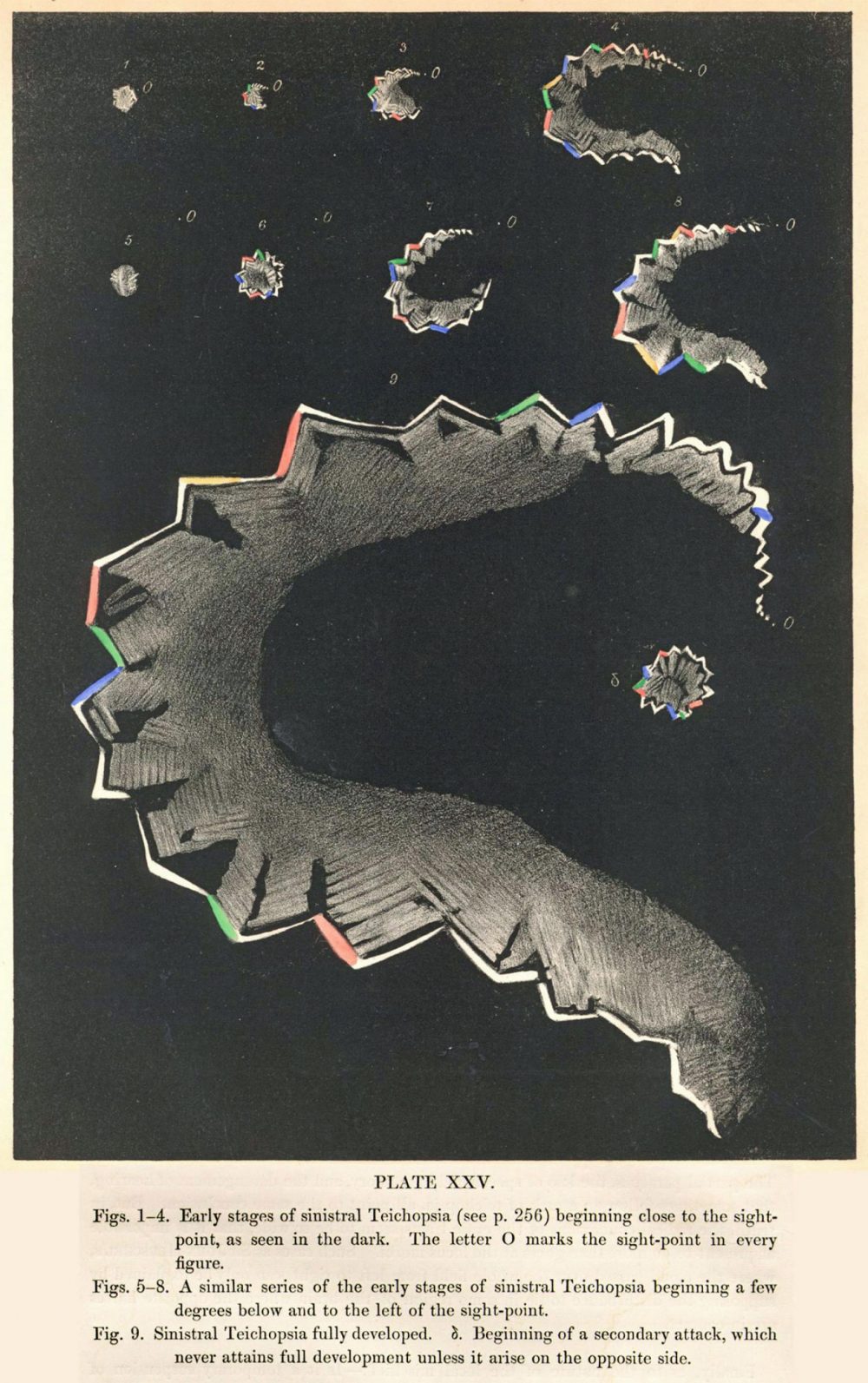

Those colors jump right out of this 1870 drawing by English physician Hubert Airy, with which he sought to capture his own visual experience of a migraine. He "first became aware of his affliction in the fall of 1854," writes National Geographic's Greg Miller, "when he noticed a small blind spot interfering with his ability to read. 'At first it looked just like the spot which you see after having looked at the sun or some bright object,' he later wrote. But the blind spot was growing, its edges taking on a zigzag shape that reminded Airy of the bastions of a fortified medieval town." As Airy describes it, "All the interior of the fortification, so to speak, was boiling and rolling about in a most wonderful manner as if it was some thick liquid all alive."

To a migraneur, that description may sound familiar, and the drawing that accompanied it in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society in 1870 may look even more so. Called "arguably the most beautiful scientific records of migraine aura ever made" by G.D. Schott in Brain, Airy's drawings "record the progress and expansion of his own visual disturbances" over their half-hour-long onset. Apart from their stark beauty, writes Miller, the set of drawings "anticipates discoveries in neuroscience that were still decades in the future," such as the assumption that the hallucinations originate in the brain rather than the eyes and that certain parts of the field of vision correspond to certain parts of the visual cortex.

"There’s still much we don’t know about migraines and migraine auras," Miller writes. "One hypothesis is that a sort of electrical wave sweeps across the visual cortex, causing hallucinations that spread across the corresponding parts of the visual field" — an idea with which Airy's early renderings also accord. And what about the source of all those colors? Electrical waves passing through parts of the brain "that contain neurons that respond to specific colors" may be responsible, but nearly 150 years after the publication of Airy's drawings, "no one really knows." Migraine research of the kind pioneered by Airy himself may have dispelled some of the mystery surrounding the affliction, but a great deal nevertheless remains. Airy's drawings, still among the most vivid representations of the visual aspect of migraines ever created, will no doubt inspire generations of future neuroscientists to find out more.

via Greg Miller at National Geographic and don't miss his book: All Over the Map: A Cartographic Odyssey.

Related Content:

Hunter S. Thompson’s Personal Hangover Cure (and the Real Science of Hangovers)

Free Guided Imagery Recordings Help Kids Cope with Pain, Stress & Anxiety

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, on Facebook, or on Instagram.

A Beautiful 1870 Visualization of the Hallucinations That Come Before a Migraine is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/2LiAyFX

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment