George Herriman’s Krazy Kat, Praised as the Greatest Comic Strip of All Time, Gets Digitized as Early Installments Enter the Public Domain

"As a cartoonist, I read Krazy Kat with awe and wonder," writes Calvin and Hobbes creator Bill Watterson in his introduction to The Komplete Kolor Krazy Kat. The creator of quite possibly the most beloved comic strip of the past thirty years calls Krazy Kat "such a pure and completely realized personal vision that the strip's inner mechanism is ultimately as unknowable as George Herriman," the artist who wrote and drew it for its entire three-decade run from 1913 to 1944. "I marvel at how this fanciful world could be so forcefully imagined and brought to paper with such immediacy. THIS is how good a comic strip can be."

High praise, especially from the hyperbole-resistant Watterson, a sharp-eyed critic of his art form and perceiver of its unrealized potential. "Quirky, individual, and uncompromised, Krazy Kat is one of the very few comic strips that takes full advantage of its medium. There are some things a comic strip can do that no other medium, not even animation, can touch, and Krazy Kat is a virtual essay on comic strip essence."

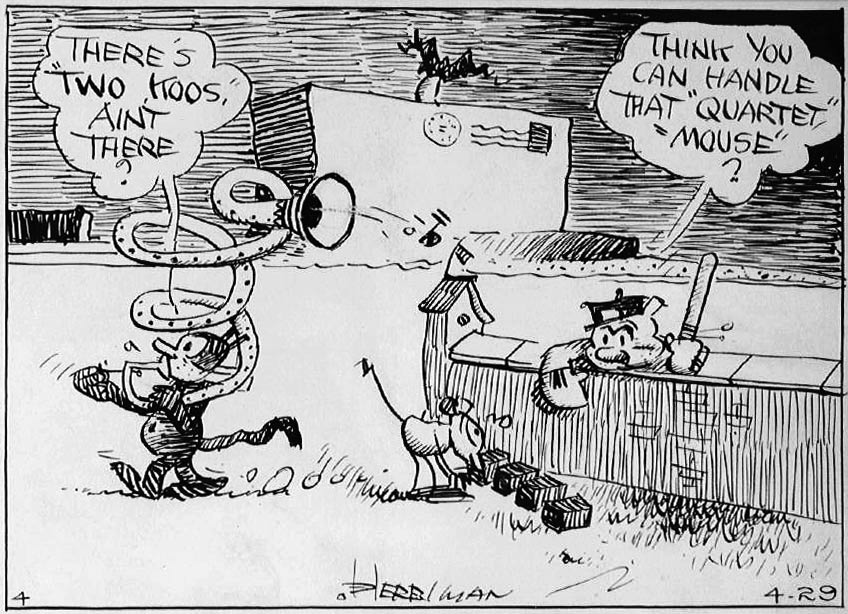

The "self-consciously baroque narrations and monologues" show that "words can be funny in themselves"; "the sky turns from black to white to zigzags and plaids simply because, in a comic strip, it CAN"; its surreal Arizona desert setting "is a character in the story, and the strip is 'about' that landscape as much as it is about the animals who populate it," Ignatz Mouse, Offissa Pupp, and the titular Krazy Kat.

Ignatz Mouse "demonstrates his contempt for Krazy by throwing bricks at her" (though their genders, so modern observers note, were never quite stable), "Krazy reinterprets the bricks as signs of love," and Offissa Pupp, the desert's lone lawman, is "obliged by duty (and regard for Krazy) to thwart and punish Ignatz's 'sin,' thereby interfering with a process that's satisfying to everyone for all the wrong reasons."

Now readers everywhere can feel that satisfaction for themselves at the web site of Krazy Kat fan Joel Franusic, who has launched a project to find and digitize (using Machine Learning) all of Herriman's strips that have so far fallen into the public domain. Franusic writes of having got into Krazy Kat in the first place because of the presence of Calvin and Hobbes in his childhood: "I remembered how Bill Watterson referenced Krazy Kat as a big reason why he insisted on getting a larger full color format for his Sunday comic strips."

I myself first picked up a Krazy Kat collection as a Calvin and Hobbes-loving elementary schooler, and soon found myself captivated by the sheer density of strangeness in its pages. But read enough of Herriman's masterwork, and that strangeness takes on a strong meaning that nevertheless differs from reader to reader. "Krazy Kat has been described as a parable of love, a metaphor for democracy, a 'surrealistic' poem, unfolding over years and years," writes Chris Ware, another of the most respected comic-strip artists alive. "It is all of these, but so much more: it is a portrait of America, a self-portrait of Herriman, and, I believe, the first attempt to paint the full range of human consciousness in the language of the comic strip." And now, 75 years after its conclusion, much more of humanity can enjoy Krazy Kat than ever. Explore digitized scans at Franusic's web site. Or pick up a copy of the new edition of The Complete Krazy Kat in Color, a color facsimile of the complete pages of Krazy Kat 1935–44.

via BoingBoing

Related Content:

Umberto Eco Explains the Poetic Power of Charles Schulz’s Peanuts

Download 15,000+ Free Golden Age Comics from the Digital Comic Museum

Download Over 22,000 Golden & Silver Age Comic Books from the Comic Book Plus Archive

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, on Facebook, or on Instagram.

George Herriman’s Krazy Kat, Praised as the Greatest Comic Strip of All Time, Gets Digitized as Early Installments Enter the Public Domain is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/2Gb1TpG

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment