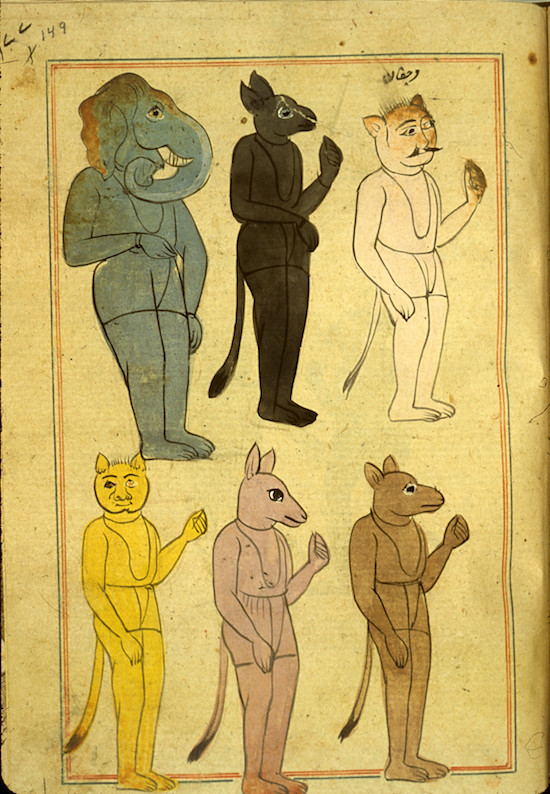

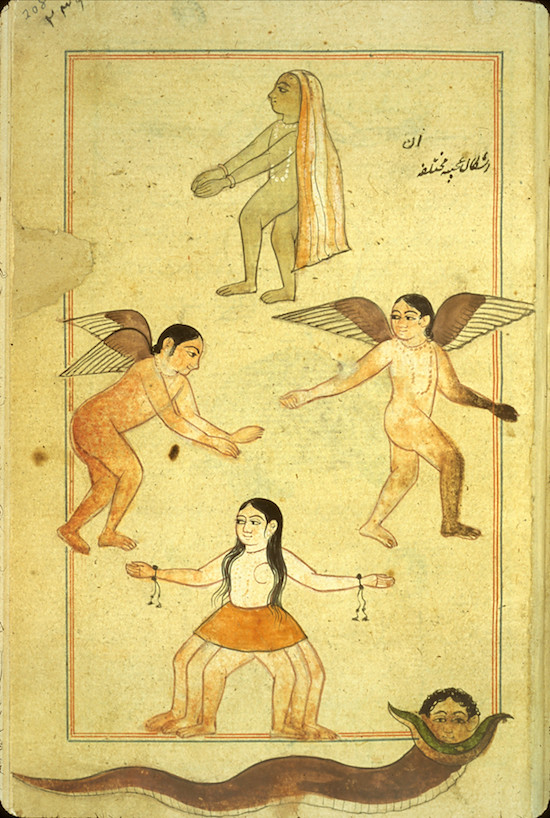

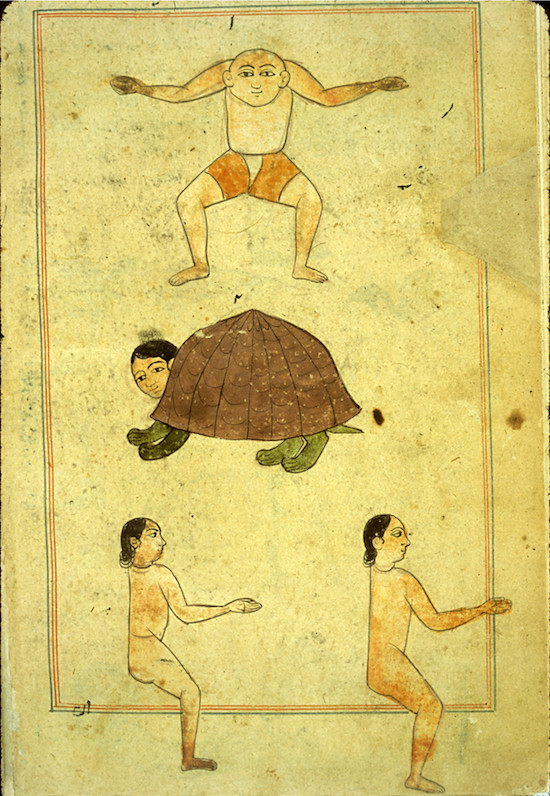

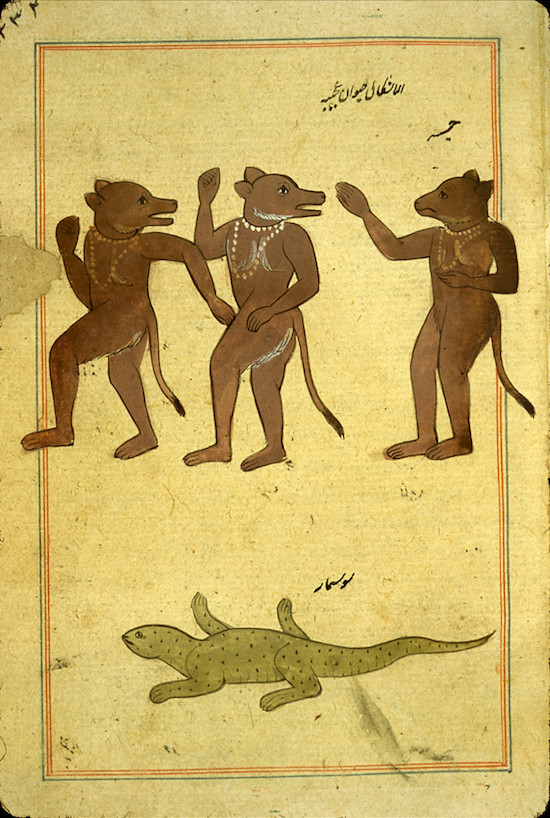

Behold Fantastical Illustrations from the 13th Century Arabic Manuscript Marvels of Things Created and Miraculous Aspects of Things Existing

Religion, history, medicine, poetry, ethnography, zoology, cosmology, political philosophy—in many a medieval text, these categories all seem to melt together. Or rather, they don’t exist separately in the way we think of them, as labels on a library shelf and courses in a catalogue. The same logical rules do not apply—the appeal to authority, for example is not a fallacy so much as a primary methodology. If knowledge came from the right prophet, scholar, or sage, it could be trusted, a mode of thinking that gave rise to monsters, phantoms, and outlandish beings of all kinds.

It’s easy to call these methods primitive, but so-called medieval ways of thinking are still very much with us, and thinkers hundreds and thousands of years ago have had surprisingly scientific approaches, despite limited resources and technologies.

We find both the fantastical and the scientific woven together in medieval manuscripts, illuminating and commenting on each other. And we find exactly that in the works of Abu Yahya Zakariya' ibn Muhammad al-Qazwini, Persian writer, physician, astronomer, geographer, and author of a 13th century treatise called ‘Aj?’ib al-makhl?q?t wa-ghar?’ib al-mawj?d?t, or Marvels of Things Created and Miraculous Aspects of Things Existing.

This work is “the most well-known example,” writes the National Library of Medicine, “of a genre of classical Islamic literature that was concerned with ‘mirabilia’ or wonders of creation.” Drawing on 50 different authors, including several ancient Islamic geographers and historians, Qazwini weaves myth, legend, and science, tying them together with stories and poetry. The Qur’an and hadith are significant sources—for a section on “angelology,” for example. When the cosmography comes down to earth, moving down through the ranks of humans, beasts, plants, and minerals, all sorts of weird, folkloric terrestrial creatures show up.

The phoenix (or Simurgh), for example, and the Homa, or paradise bird—which lands on someone’s head and instantly makes them king—sit comfortably next to eagles, vultures, and ostriches, all of which are construed as marvelous or miraculous in some way.

The treatise covered all the wonders of the world, and the variety of the subject matter (humans and their anatomy, plants, animals, strange creatures at the edges of the inhabited world, constellations of stars, zodiacal signs, angels, and demons) provided great scope for the artist.

First written in Arabic in the late 1200s and dedicated to the governor of Baghdad, the manuscript was “immensely popular” in the Islamic world. It was translated into Persian and Turkish and copied out in richly illustrated editions for centuries. The images here come from a Persian translation, “thought to hail from 17th-century Mughal India,” writes The Public Domain Review, and the art vividly displays the “eclectic mix of topics” in al-Qazwini’s book. These were subjects that “challenged understanding”—often because they concerned things that do not exist, and often because they described natural phenomenon that could not yet be explained.

“From humans and their anatomy to strange mythical creatures; from plants and animals to constellations of stars and zodiacal signs,” The Public Domain Review explains, the treatise purported to survey all the “known” world. Al-Qazwini embellished his explorations for entertainment purposes, but he also created extensive taxonomies and described practical science like the use of “a type of pitch or tar that we today know as asphalt,” San Francisco’s Asian Art Museum notes in their catalogue description of another illustrated manuscript, in Arabic, from 1650. For al-Qazwini and his readers, as for other 13th-century scholars, writers, and readers around the world, the boundaries between faith, fact, and fiction were permeable, and imagination sometimes seems to have been the ultimate authority.

Related Content:

700 Years of Persian Manuscripts Now Digitized and Available Online

The Complex Geometry of Islamic Art & Design: A Short Introduction

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Behold Fantastical Illustrations from the 13th Century Arabic Manuscript Marvels of Things Created and Miraculous Aspects of Things Existing is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/2k15Bua

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment