Can Artificial Intelligence Decipher Lost Languages? Researchers Attempt to Decode 3500-Year-Old Ancient Languages

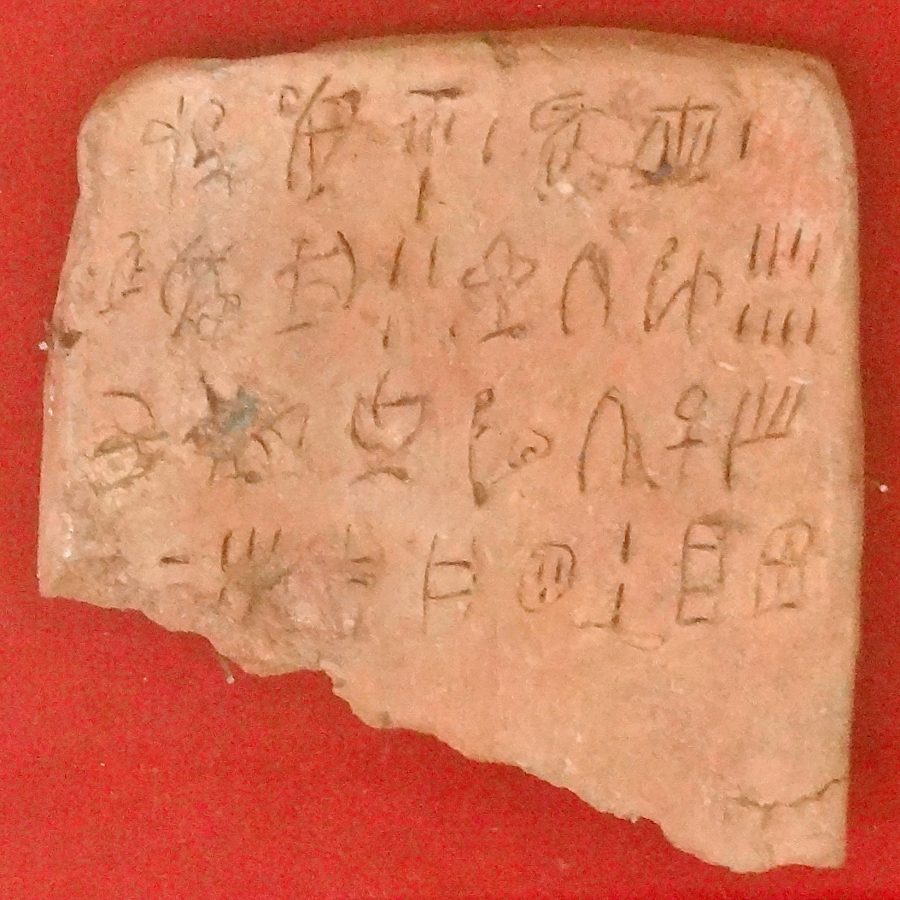

Image by Olaf Tausch via Wikimedia Commons

We may not see warp drives any time soon, but another piece of Star Trek tech, the universal translator, maybe become a reality in our lifetime, if it hasn’t already. Machine learning “has proven to be very competent” when it comes to translation, “so much so that the CEO of one of the world’s largest employers of human translators has warned that many of them should be facing up the stark reality of losing their job to a machine,” writes Bernard Marr at Forbes.

But the fact that AI can do things humans do doesn't mean that it does those things well. One Google researcher put the case plainly in an interview with Wired: “People naively believe that if you take deep learning and… 1,000 times more data, a neural net will be able to do anything a human being can do, but that’s just not true.” AI translators have advanced significantly in the past few years, with Google’s Translatotron prototype (yes, that’s its real name), promising to interpret “tone and cadence.” Still, AI translations are often stilted, awkward, and occasionally incomprehensible approximations that no human would come up with.

Does AI’s limitations with living language hinder its ability to decipher very long dead ones, whose orthography, grammar, and syntax has been completely lost? Yuan Cao from Google’s AI lab and Jiaming Luo and Regina Barzilay from MIT put machine learning to the test when they developed a “system capable of deciphering lost languages.” They took a very different approach “from the standard machine translation techniques,” reports the MIT Technology Review, using less data instead of more, a technique they call "minimum-cost flow."

The researchers tested their translation machine on both the 3500-year-old Linear B and Ugaritic, an ancient form of Hebrew, both of which have already been deciphered by people. Still, the AI was “able to translate both languages with remarkable accuracy,” with a rate of 67.3% in the translation of cognates in Linear B. The far older Bronze Age Minoan script Linear A, however (see it at the top), “one of the earliest forms of writing ever discovered… is conspicuous for its absence.” No human has yet been able to decipher it.

A lost language translator machine that only works on languages that have already been translated (it needs preexisting data on the progenitor language to function) may not seem particularly useful. Then again, it could be one step in the direction of what the authors call the “automatic decipherment of lost languages," those that humans can’t already work out on their own. Read the paper “Neural Decipherment via Minimum-Cost Flow: From Ugaritic to Linear B” at arXiv.

Related Content:

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Can Artificial Intelligence Decipher Lost Languages? Researchers Attempt to Decode 3500-Year-Old Ancient Languages is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/2JJlHCx

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment