Why Civilization Collapsed in 1177 BC: Watch Classicist Eric Cline’s Lecture That Has Already Garnered 5.5 Million Views

Eric Cline is a man of the Bronze Age. “If I could be reincarnated backwards,” he says in the lecture above, “I would choose to live back then. I’m sure I would not live more than about 48 hours, but it’d be a good 48 hours.” He may give himself too little credit: as he goes on to demonstrate in the hour that follows, he has as thorough an all-around knowledge of life in the Bronze Age as anyone alive in the 21st century. But of course, his prospects for survival in that era — or indeed anyone’s — depend on which part of it we’re talking about. The Bronze Age lasted a long time, from roughly 3300 to 1200 BC — at the end of which, ancient-history specialists agree, civilization collapsed.

What the specialists don’t quite agree on is how it happened. Cline makes his own case in the book 1177 BC: The Year Civilization Collapsed. The title, which seems to have been the result of the publishing industry’s invincible enthusiasm for naming books after years, may soon need an update: as Cline admits, it reflects a convention among scholars about how to label the titular event that has just been revised, and has since been revised back. And in any case, the collapse of civilization among the distinct but interconnected Egyptians, Hittites, Canaanites, Cypriots, Minoans, Mycenaeans, Assyrians, and Babylonians of the Bronze Age took not a year, he explains, but more like a century.

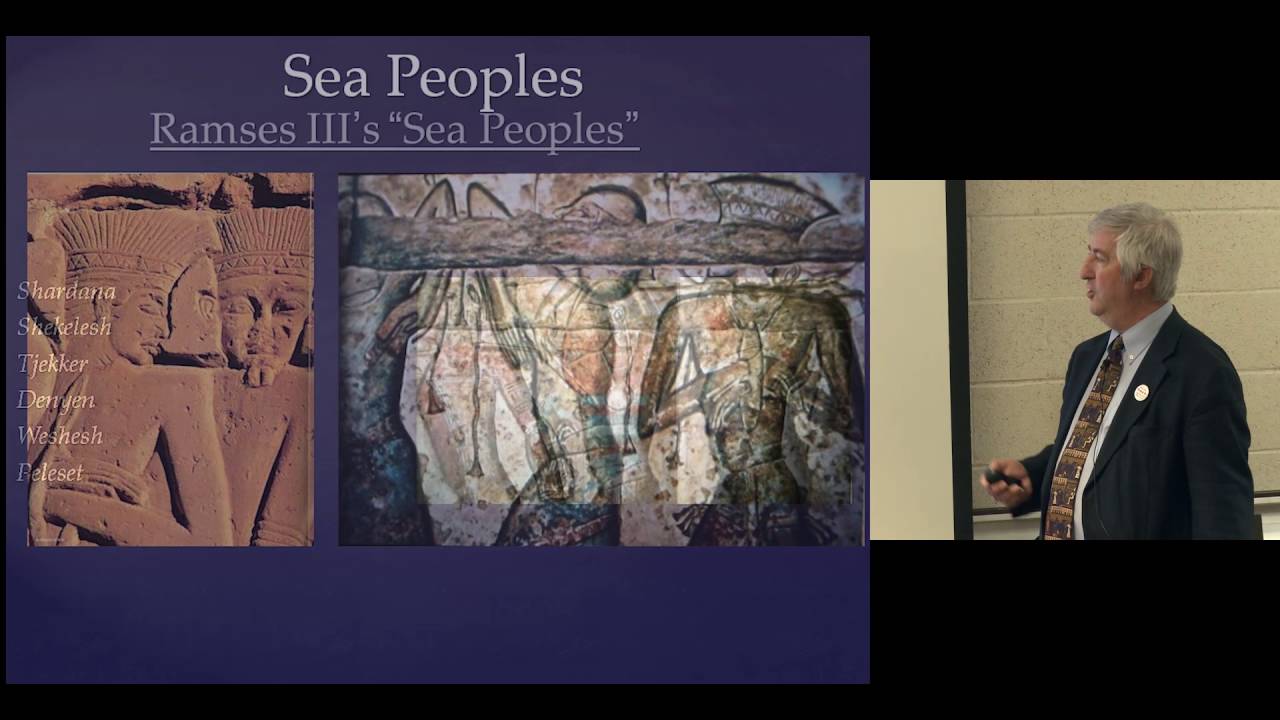

This complicated process has no one explanation — and more to the point, no one cause. Many flourishing cities of Bronze Age civilization were indeed destroyed by 1177 BC or soon thereafter. The “old, simple explanation” for this was that “a drought caused famine, which eventually caused the Sea Peoples to start moving and creating havoc, which caused the collapse.” Cline opts to include these factors and others, including earthquakes and rebellions, whose effects spread to afflict all parts of this early “globalized” part of the world. The result was a “systems collapse,” involving the breakdown of “central administrative organization,” the “disappearance of the traditional elite class,” the “collapse of the centralized economy,” as well as “settlement shifts and population decline.”

Systems collapses have also happened in other places and at other times. Given the enormous intensification of globalization since the Bronze Age and the continued threats issued by the natural world, could another happen here and now? Pointing to the climate change, famines and droughts, earthquakes, rebellions, acts of bellicosity, and economic troubles in evidence today, Cline adds that “the only thing missing are the Sea Peoples” — and even then suggests that ISIS and refugees from Syria could be playing a similarly disruptive role. Given that this talk has racked up more than five and a half million views so far, it seems he makes a convincing case, though the appeal could owe as much to his jokes. Not all of us, he acknowledges, will accept the relevance of the subject: “It’s history,” as we reassure ourselves. “It never repeats itself.”

Related Content:

The History of Civilization Mapped in 13 Minutes: 5000 BC to 2014 AD

Get the History of the World in 46 Lectures: A Free Online Course from Columbia University

M.I.T. Computer Program Alarmingly Predicts in 1973 That Civilization Will End by 2040

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Why Civilization Collapsed in 1177 BC: Watch Classicist Eric Cline’s Lecture That Has Already Garnered 5.5 Million Views is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook and Twitter, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/3xIPSPY

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment