Those who grew up with the BBC sci-fi series Doctor Who watched from “behind the sofa,” a popular phrase associated with the show for the rubbery, bug-eyed monsters it held in store each week for loyal viewers. Although it may be hard for those who didn’t experience it in their formative years to understand, Doctor Who has frequently been voted the scariest TV show of all time, over grislier, big-budget series like The Walking Dead, and has done so without losing its sense of humor, a testament to the conceit of “regeneration” keeping things fresh by updating the Doctor and his companions every few years.

Space monsters, Daleks, Cybermen, and a revolving cast, however, were not part of Doctor Who’s original remit. The show began as an educational program on the BBC, and this explains many of its integral parts, which have remained throughout its first run from 1963 to 1989 and its revival from 2005 to the present. These elements include the TARDIS, companions of various ages, the Coal Hill School, and the Doctor himself, a Time Lord from the planet Gallifrey with interstellar technology and a dodgy memory.

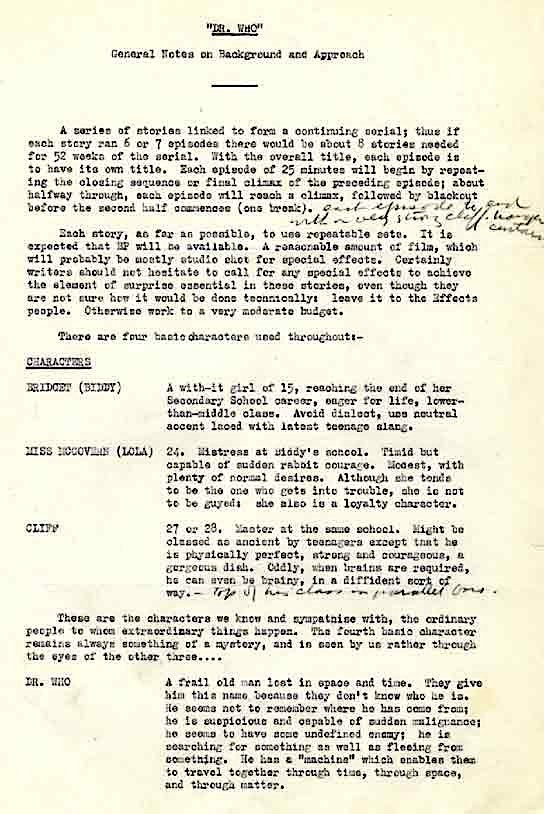

We find the core premise in the show’s pilot episode and original 4-part series, An Unearthly Child, which introduced William Hartnell as the Doctor, Carole Ann Ford as his granddaughter, Susan Foreman (originally named Barbara, or “Biddy”), and Jaqueline Hill and William Russell as school teachers Barbara Wright and Ian Chesterton. BBC drama head Sydney Newman had tasked writers with creating a family educational show to meet the network’s public service mandate, and came up with the idea of a science fiction show as a way to have characters visit historical periods and talk about science in an entertaining way.

“Doctor Who’s early historical stories emphasize education by downplaying the programme’s fantasy with minimal science-fiction elements,” writes Tom Steward at Deletion. The idea of a time machine bigger on the inside than the outside came from Newman. Writer Anthony Coburn turned it into a police box after a note from Newman asking for a “tangible” symbol. Newman “instructed writers to ‘get across the basis of teaching of educational experience.'” When they came back with a story about Daleks, he balked: “No bug-eyed monsters,” he wrote, no alien baddies, no actors in rubber suits. This was to be a serious show about serious educational subjects. Script changes and technical challenges meant months of setback and delays.

It was difficult for some critics to take the resulting four episode arc particularly seriously. The first episode showed Barbara and Ian discovering the TARDIS in a London junkyard. Then they are all transported to the prehistoric past, where they observe (and escape) a power struggle among prehistoric cave people. (Guardian critic Mary Crozier lamented that the “wigs and furry pelts and clubs were all ludicrous.”) The show’s debut was also inauspicious: November 23, 1963, the day after John F. Kennedy’s assassination. The BBC reran the first episode the next week and picked up another 2 million viewers.

Still, it had become clear after the first series that in order to survive, Doctor Who would have “to give the public what they wanted,” Steward writes, “rather than what was good for them.” Thus, the Daleks debuted in the second season, and by the mid-60s, historical stories were replaced with “fantasies in historical costume featuring anachronistic villains or monsters.” The show became a weekly creature feature and introduced terrifying villains like Davros, the Daleks’ creator, a cross between a Strangelove-like Nazi scientist and Star Wars’ clone-happy Emperor Palpatine (Davros came first).

The costumes may look silly in hindsight, but as childhood Who fan Charlie Jane Anders writes at io9, “those of us who are adults now didn’t have huge screen HD televisions when we were kids.” (And those of us who remember it, remember being terrified by equally goofy costuming in The Land of the Lost.) Look past the low-budget effects and Doctor Who becomes pure horror, exploring very dark territory with only a sonic screwdriver, a few friends, and a quirky sense of humor — or 13 quirky senses of humor, including Jodie Whittaker’s as the current Doctor and first woman to fill the role.

As you can see from the clips of the first episode above, Doctor Who established its weird air of existential dread from the start with Delia Derbyshire’s otherworldly theme and some avant-garde camera effects in lieu of bigger-budget spectacles. The show did not retain much from its educational beginnings aside from the key characters and the look and feel of the TARDIS. It was “seen to have failed as pedagogy,” writes Steward, but as a body of science fiction lore that continues to stay relevant, it has all sorts of lessons to teach about courage, companionship, and the value of the right tool for the right job.

Related Content:

30 Hours of Doctor Who Audio Dramas Now Free to Stream Online

The Fascinating Story of How Delia Derbyshire Created the Original Doctor Who Theme

A Detailed, Track-by-Track Analysis of the Doctor Who Theme Music

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

How Doctor Who First Started as a Family Educational TV Program (1963) is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook and Twitter, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/3stiPhO

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment