When Ken Kesey and his Merry Pranksters kicked off Haight-Ashbury’s counterculture in the 1960s, LSD was the key ingredient in their potent mix of drugs, the Hell’s Angels, the Beat poets, and their local band The Warlocks (soon to become The Grateful Dead). Kesey administered the drug in “Acid Tests” to find out who could handle it (and who couldn’t) after he stole the substance from Army doctors, who themselves administered it as part of the CIA’s MKUltra experiments. Not long afterward, Grateful Dead soundman Owsley “Bear” Stanley synthesized “the purest form of LSD ever to hit the street,” writes Rolling Stone, and became the country’s biggest supplier, the “king of acid.”

Whatever uses it might have had in psychiatric settings — and there were many known at the time — LSD was made illegal in 1968 by the U.S. government, repressing what the government had itself helped bring into being. But it has since returned with newfound respectability. “Once dismissed as the dangerous dalliances of the counterculture,” writes Nature, psychedelic drugs are “gaining mainstream acceptance” in clinical treatment. Psilocybin, MDMA, and LSD “have been steadily making their way back into the lab,” notes Scientific American. “Scientists are rediscovering what many see as the substances’ astonishing therapeutic potential.”

None of this comes as news to San Francisco fixture Mark McCloud. “In the same moralistic manner many San Franciscans pontificate on the health benefits of marijuana,” writes Gregory Thomas at Mission Local, “McCloud and his friends tout the merits of acid.” Next to curing “anxiety, depression and ‘marital problems,’” it is also an important source of folk art, says McCloud, the owner and sole proprietor of the informally-named “LSD Museum” housed in his three-story Victorian home in San Francisco.

His mission in creating and maintaining the museum formally called the Institute of Illegal Images, he says, is to “preserve a ‘skeletal’ remnant of San Francisco’s drug-induced 1960s legacy, ‘so maybe our children can better understand us.’”

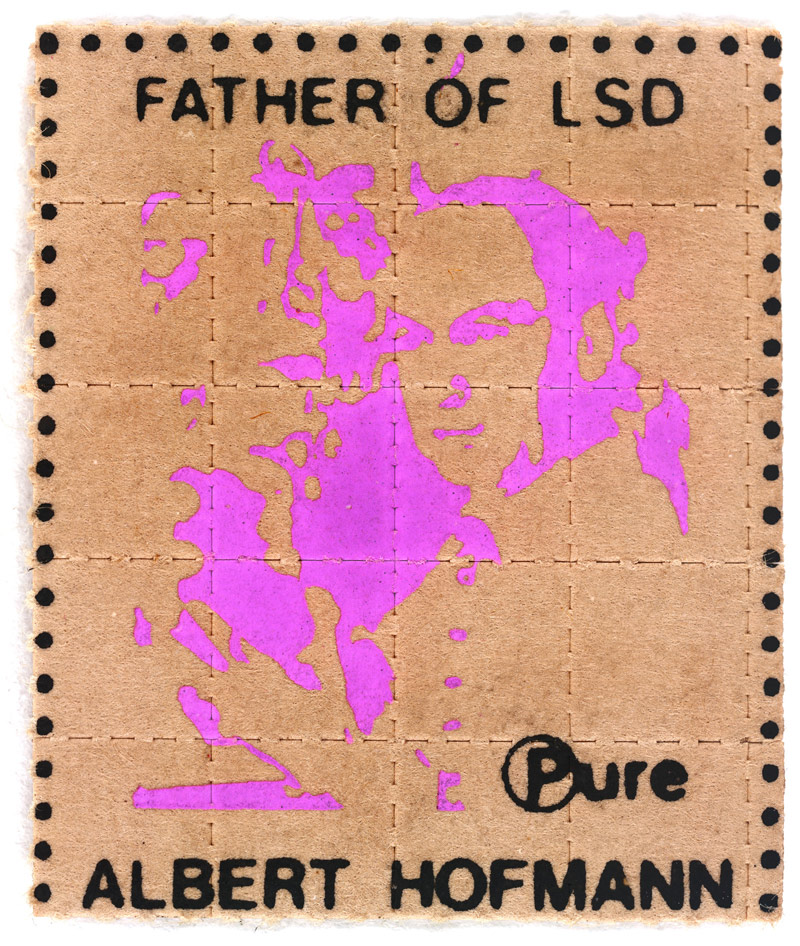

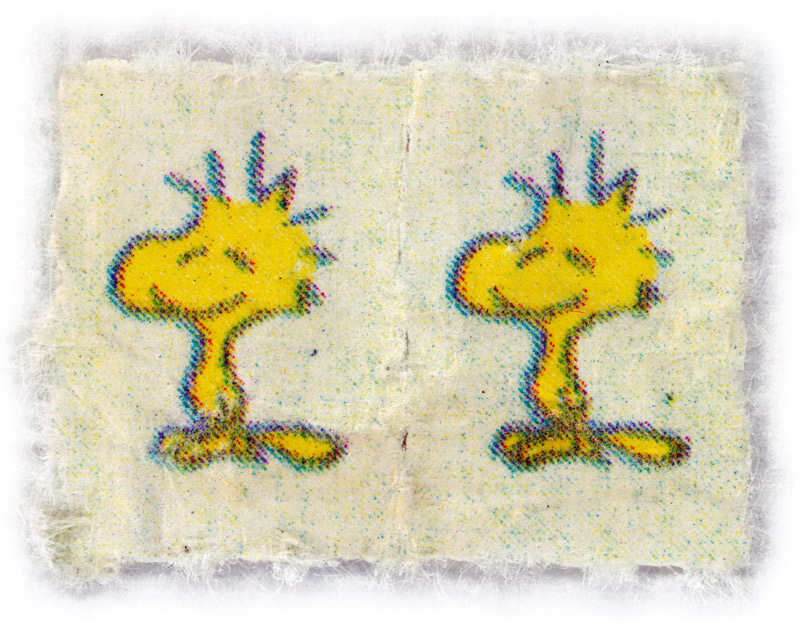

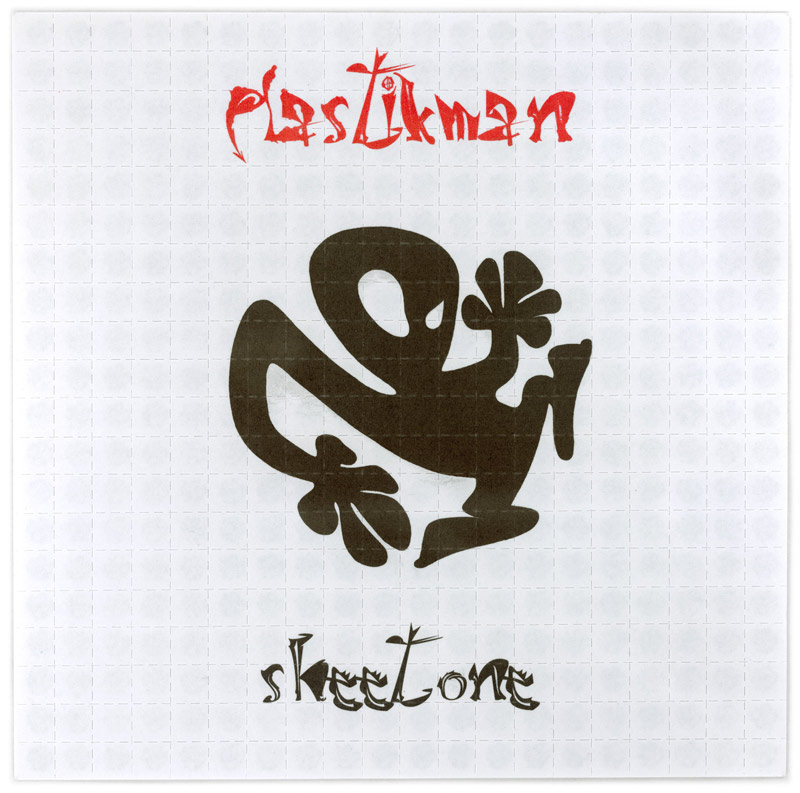

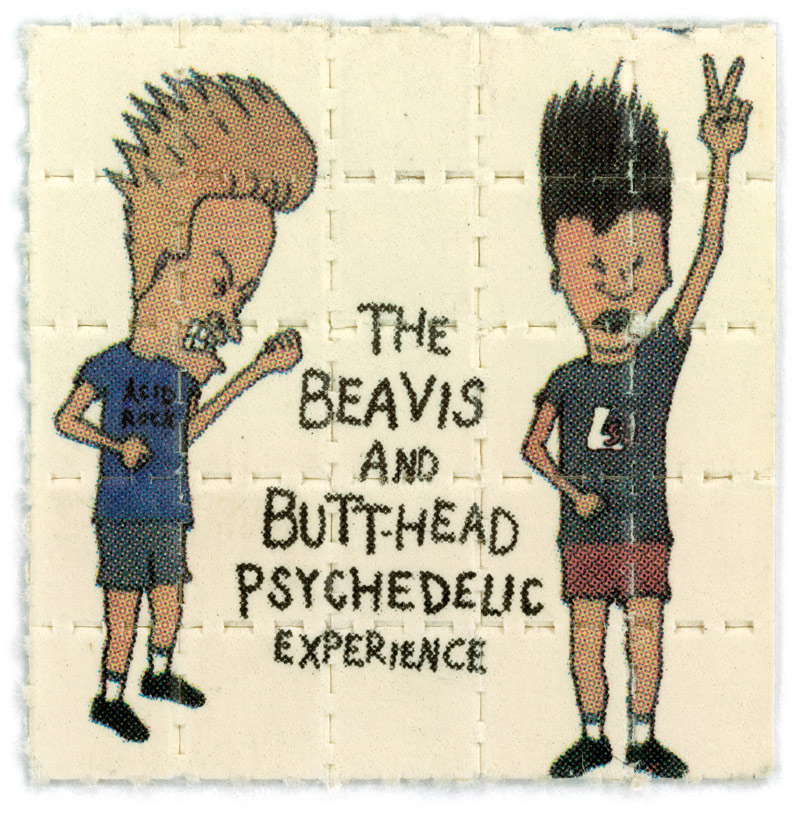

Specifically, as Culture Trip explains, McCloud preserves the art on sheets of blotter acid. As is clear from the many pop cultural references on blotter art — like Beavis and Butthead and techno artist Plastikman (who named his debut album Sheet One) — the 60s blotter acid legacy extended far beyond its founders’ vision in underground scenes throughout the 70s, 80s, 90s, and oughts.

Also known as the Blotter Barn or the Institute of Illegal Images, McCloud’s house is located on 20th Street between Mission and Capp. The house preserves over 33,000 sheets of LSD blotter, treating them like tiny little works of art. Most of the sheets are framed and hanging on McCloud’s walls, decorating the home with vibrant colors and patterns, and the rest are kept safe in binders. The house also features a perforation board, allowing McCloud to turn any work of art sized 7.5 by 7.5 inches into 900 pieces, as is typical for LSD blotter sheets.

McCloud has faced intense scrutiny from the FBI, and on a couple of occasions — in 1992 and again in 2001 — arrest and trial by “not very sympathetic” juries, who nonetheless acquitted him both times. Despite the fact that he has a larger collection of blotter acid sheets than the DEA, he and his museum have withstood prosecution and attempts to shut them down, since all the sheets in his possession have either never been dipped in LSD or have become chemically inactive over time. (The museum’s website explains the origins of “blotter” paper as a means of preparing LSD doses after the drug was criminalized in California in 1966.)

“What fascinates me about blotter is what fascinates me about all art. It changes your mind,” says McCloud in the Wired video at the top of the post. None of his museum’s artwork will change your mind in quite the way it was intended, but the mere association with hallucinogenic experiences is enough to inspire the artists “to build the myriad of subject matter appearing on the blotters,” Atlas Obscura writes, “ranging from the spiritual (Hindu gods, lotus flowers) to whimsical (cartoon characters), as well as cultural commentary (Gorbachev) and the just plain demented (Ozzy Osbourne).”

The museum does not keep regular hours and was only open by appointment before COVID-19. These days, it’s probably best to make a virtual visit at blotterbarn.com, where you’ll find dozens of images of acid blotter paper like those above and learn much more about the history and culture of LSD during long years of prohibition — a condition that seems poised to finally end as governments give up the wasteful, punishing War on Drugs and allow scientists and psychonauts to study and explore altered states of consciousness again.

Related Content:

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Take a Trip to the LSD Museum, the Largest Collection of “Blotter Art” in the World is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook and Twitter, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/3sjyIrf

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment