Build Wooden Models of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Great Building: The Guggenheim, Unity Temple, Johnson Wax Headquarters & More

Frank Lloyd Wright had his eccentricities, in not just his personal and professional conduct but also the very language with which he described the world. Among the enduringly fascinating elements of his idiolect is the word Usonian, which refers to things of or pertaining to the United States of America. Wright didn’t coin the term: its earliest recorded user is the early 20th-century writer James Duff Law, who declared that “We of the United States, in justice to Canadians and Mexicans, have no right to use the title ‘Americans’ when referring to matters pertaining exclusively to ourselves.” The most famous architect in American history took Usonian further, using it to label an American architectural sensibility — of, naturally, his own design.

Though Wright did envision an ideally Usonian city, his clearest expressions of the aesthetic stand today in the form of the Usonian houses. Built between 1934 and 1958, these sixty or so residences take advantage, as Wright saw it, of the range of distinctive settings offered up by the landscapes of the United States.

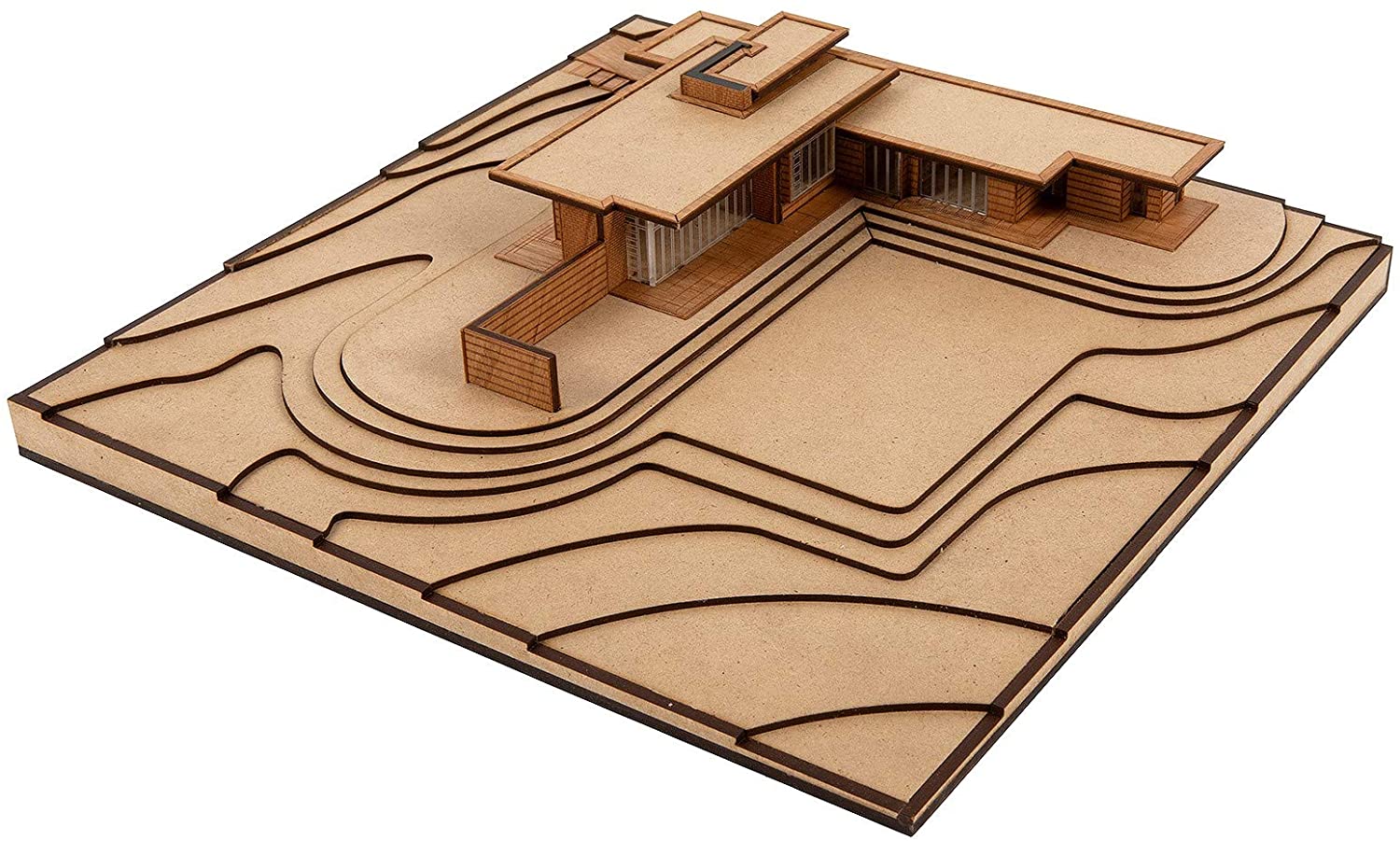

Designed with features like garden terraces, clerestory windows, flat roofs with wide overhangs, and easy visual and physical passage between the indoors and outdoors, these urban-rural hybrids still today draw the admiration of architects and non-architects alike. But truly to understand a Usonian house, perhaps you must build one yourself: luckily, the Little Building Company offers a model kit that lets you do just that.

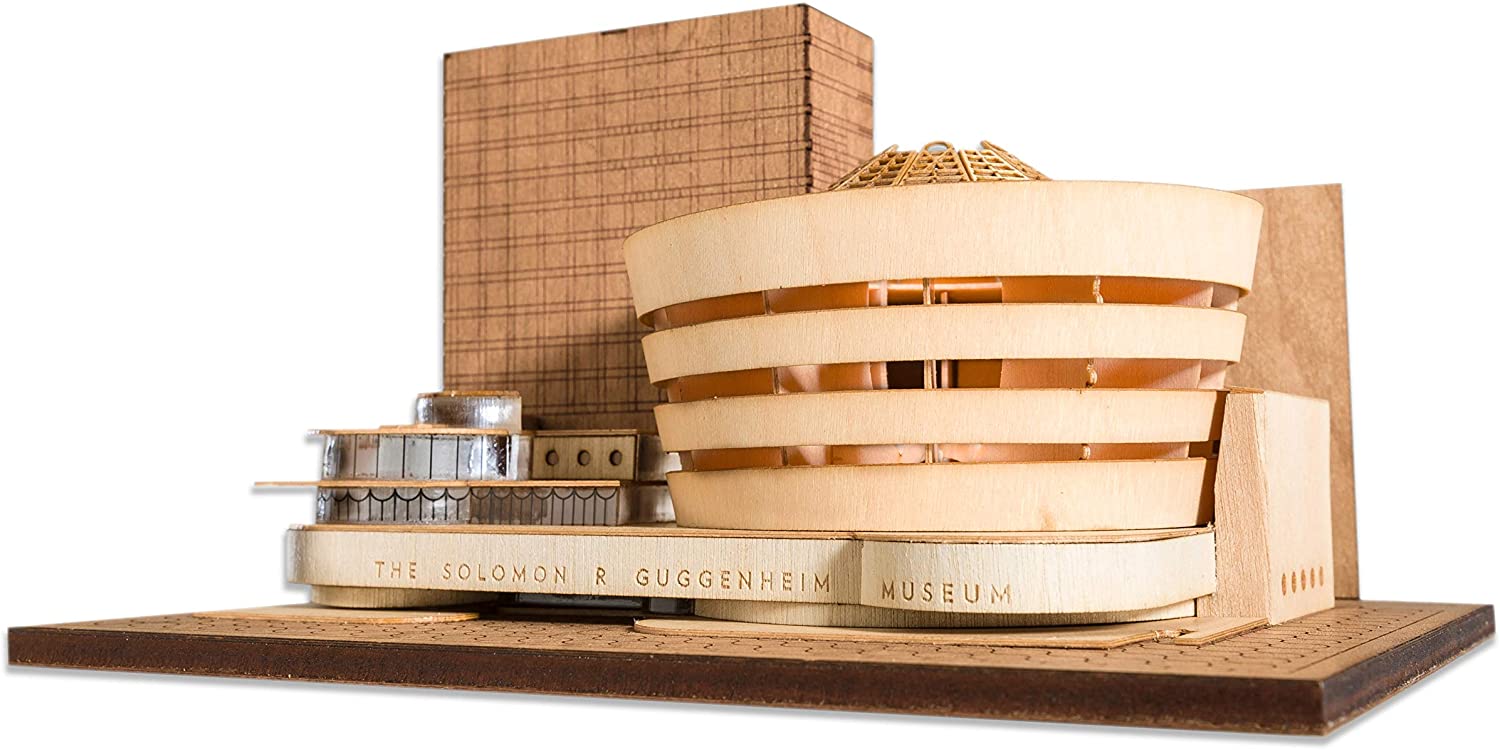

Their Wright lineup also includes miniature wooden versions of his 1908 Unity Temple in Oak Park, his 1937 Johnson Wax Headquarters in Racine, and his 1937 Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York. The differences in scale and complexity between these buildings make for a natural model-building difficulty curve: once you’ve done a Wright house, you’ll be ready for a Wright temple; once you’ve done a Wright temple, you’ll be ready for a Wright corporate headquarters, and so on. Not only will the effort hone your manual dexterity, it will heighten your appreciation for the American architecture-defining innovations Wright pulled off in the early 20th century. But do you have to be from the United States to understand the Usonian? Based in Australia and selling to the world, the Little Building Company suggests not.

Related Content:

Frank Lloyd Wright Designs an Urban Utopia: See His Hand-Drawn Sketches of Broadacre City (1932)

The Modernist Gas Stations of Frank Lloyd Wright and Mies van der Rohe

How Frank Lloyd Wright’s Son Invented Lincoln Logs, “America’s National Toy” (1916)

That Far Corner: Frank Lloyd Wright in Los Angeles – a Free Online Documentary

Omoshiroi Blocks: Japanese Memo Pads Reveal Intricate Buildings As The Pages Get Used

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Build Wooden Models of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Great Building: The Guggenheim, Unity Temple, Johnson Wax Headquarters & More is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook and Twitter, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/2WHxBpV

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment