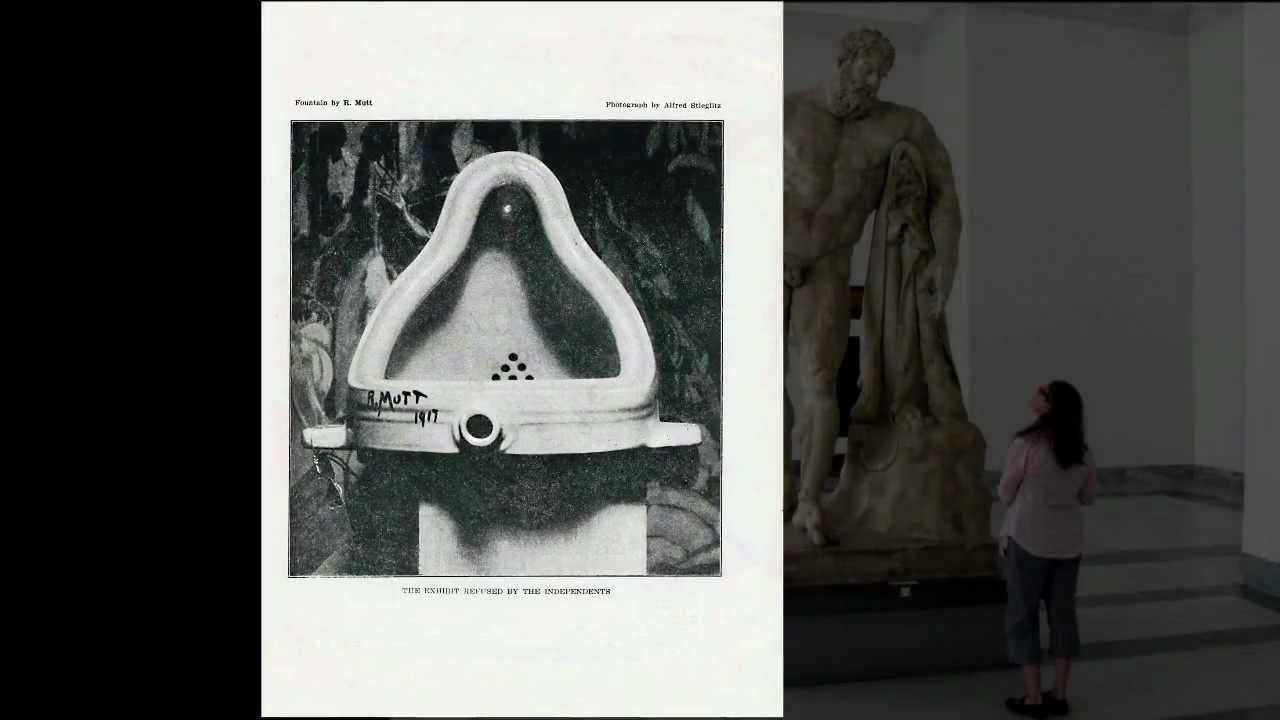

To our way of thinking, the question is not whether Marcel Duchamp conceived of Fountain, history’s most famous urinal, as art or prank.

Nor is it the ongoing controversy as to whether the piece should be attributed to Duchamp or his friend, avant-garde poet and artist Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven.

The question is why more civilians don’t head for the men’s room armed with black paint pens (or alternatively, die-cut stickers) to enhance every urinal they encounter with the signature of the non-existent “R. Mutt.”

The art world bias that was being tested in 1917, when the signed urinal was unsuccessfully submitted to an unjuried exhibition at the Society of Independent Artists, has not vanished entirely, but as curator Sarah Urist Green explains in the above episode of The Art Assignment, the past hundred years has witnessed a lot of conceptual art afforded space in even the most staid institutions.

Fountain was a premeditated piece, but sometimes, these artworks, or pranks, if you prefer — Green favors letting each viewer reach their own conclusions — are more spontaneous in nature.

She references the case of two teenaged boys who, underwhelmed by a Mike Kelley stuffed animal installation at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, positioned a pair of eyeglasses in such a way that other visitors assumed they, too, were part of an exhibit.

One of the boys told The New York Times that “when art is more abstract, it is more difficult to interpret,” causing him to lose interest.

“We had a good laugh about it,” the other added.

And that, for us, gets to the heart of Fountain’s enduring power.

Plenty of art world stunts, whether their intention was to shock, critique, or screw with the gatekeepers have been lost to the ages.

Fountain, at heart, is a particularly memorable kind of funny…

Funny in the same way poet Russell Edson’s “With Sincerest Regrets” is funny:

WITH SINCEREST REGRETS

for Charles Simic

Like a white snail the toilet slides into the living room, demanding to be loved. It is impossible, and we tender our sincerest regrets.In the book of the heart there is no mention made of plumbing.

And though we have spent our intimacy many times with you, you belong to a rather unfortunate reference, which we would rather not embrace…

The toilet slides out of the living room like a white snail, flushing with grief…

More recent art world controversies — Chris Ofili’s “The Holy Virgin Mary” and Andres Serrano’s Piss Christ — arose from the juxtaposition of serious religious subject matter with bodily fluids.

By contrast, Fountain took the piss out of a secular high church — the established art world.

And it did so with a factory-fresh urinal, no more gross than a porcelain dinner plate.

No wonder people couldn’t stop talking about it!

We still are.

Green recounts how performance artists Cai Yuan and Jian Jun Xi attempted to “celebrate the spirit of modern art” by urinating on the Tate Modern’s Fountain replica in 2000.

That performance, titled “Two artists piss on Duchamp’s Urinal” was “intended to make people re-evaluate what constituted art itself and how an act could be art.”

Their action might have made a more elegant — and funnier — statement had the Fountain replica not been displayed inside a vitrine.

Still, drawing attention to their inability to hit the target might, as Green suggests, highlight how museum culture “fetishizes and protects the objects” it, or history, deems worthy.

Related Content:

When Brian Eno & Other Artists Peed in Marcel Duchamp’s Famous Urinal

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

What Made Marcel Duchamp’s Famous Urinal Art–and an Inventive Prank is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook and Twitter, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/3yhT9XE

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment