Ursula K. Le Guin’s Tao Te Ching: How the Sci-Fi Legend Created a Landmark Rendition of the Taoist Classic (1997)

Brenda (laughing): Can you imagine a Taoist advertising agency? “Buy this if you feel like it. If it’s right. You may not need it.”

Ursula: There was an old cartoon in The New Yorker with a guy from an advertising agency showing his ad and the boss is saying “I think you need a little more enthusiasm Jones.” And his ad is saying, “Try our product, it really isn’t bad.”

Perhaps no Chinese text has had more lasting influence in the West than the Tao Te Ching, a work so ingrained in our culture by now, it has become a “changeless constant,” writes Maria Popova. “Every generation of admirers has felt, and continues to feel, a prescience in these ancient teachings so astonishing that they appear to have been written for their own time.” It speaks directly to us, we feel, or at least, that’s how we can feel when we find the right translation.

Admirers of the Taoist classic have included John Cage, Franz Kafka, Bruce Lee, Alan Watts, and Leo Tolstoy, all of whom were deeply affected by the millennia-old philosophical poetry attributed to Lao Tzu. That’s some heavy company for the rest of us to keep, maybe. It’s also a list of famous men. Not every reader of the Tao is male or approaches the text as the utterances of a patriarchal sage. One famous reader had the audacity to spend decades on her own, non-gendered, non-hierarchical translation, even though she didn’t read Chinese.

It’s not quite right to call Ursula Le Guin’s Tao Te Ching a translation, so much as an interpretation, or a “rendition,” as she calls it. “I don’t know Chinese,” she said in an interview with Brenda Peterson, “but I drew upon the Paul Carus translation of 1898 which has Chinese characters followed by a transliteration and a translation.” She used the Carus as a “touchstone for comparing other translations,” and started, in her twenties, “working on these poems. Every decade or so I’d do another chapter. Every reader has to start anew with such an ancient text.”

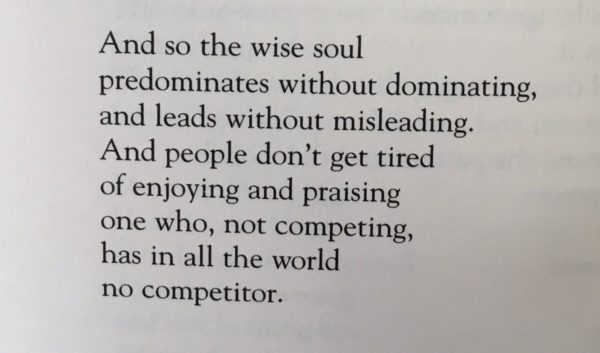

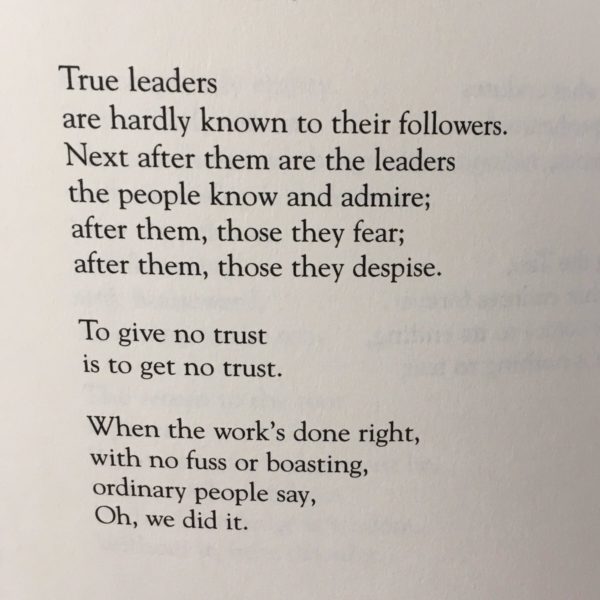

Le Guin drew out inflections in the text which have been obscured by translations that address the reader as a Ruler, Sage, Master, or King. In her introduction, Le Guin writes, “I wanted a Book of the Way accessible to a present-day, unwise, unpowerful, perhaps unmale reader, not seeking esoteric secrets, but listening for a voice that speaks to the soul.” To immediately get a sense of the difference, we might contrast editions of Arthur Waley’s translation, The Way and Its Power: a Study of the Tao Te Ching and Its Place in Chinese Thought, with Le Guin’s Tao Te Ching: A Book about the Way and the Power of the Way.

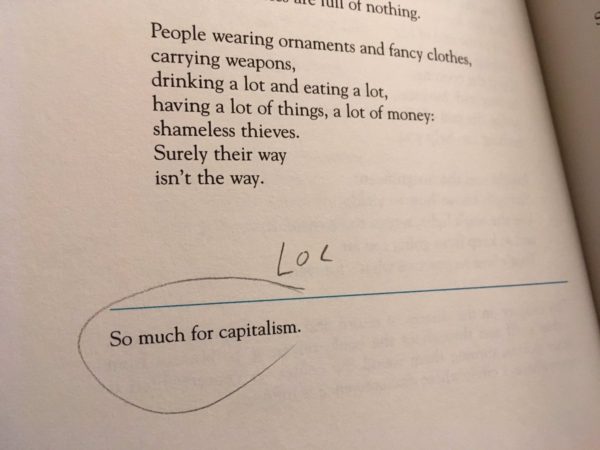

Waley’s translation “is never going to be equaled for what it does,” serving as a “manual for rulers,” Le Guin says. It was also designed as a guide for scholars, in most editions appending around 100 pages of introduction and 40 pages of opening commentary to the main text. Le Guin, by contrast, reduces her editorial presence to footnotes that never overwhelm, and often don’t appear at all (one note just reads “so much for capitalism”), as well as a few pages of endnotes on sources and variants. “I didn’t figure a whole lot of rulers would be reading it,” she said. “On the other hand, people in positions of responsibility, such as mothers, might be.”

Her version represents a lifelong engagement with a text Le Guin took to heart “as a teenage girl” she says, and found throughout her life that “it obviously is a book that speaks to women.” But her rendering of the poems does not substantially alter the substance. Consider the first two stanzas of her version of Chapter 11 (which she titles “The uses of not”) contrasted with Waley’s CHAPTER XI.

Waley

We put thirty spokes together and call it a wheel;

But it is on the space where there is nothing that the

usefulness of the wheel depends.

We turn clay to make a vessel;

But it is on the space where there is nothing that the

usefulness of the vessel depends.Le Guin

Thirty spokes

meet in the hub.

Where the wheel isn’t

is where is it’s useful.Hollowed out,

clay makes a pot.

Where the pot’s not

is where it’s useful.

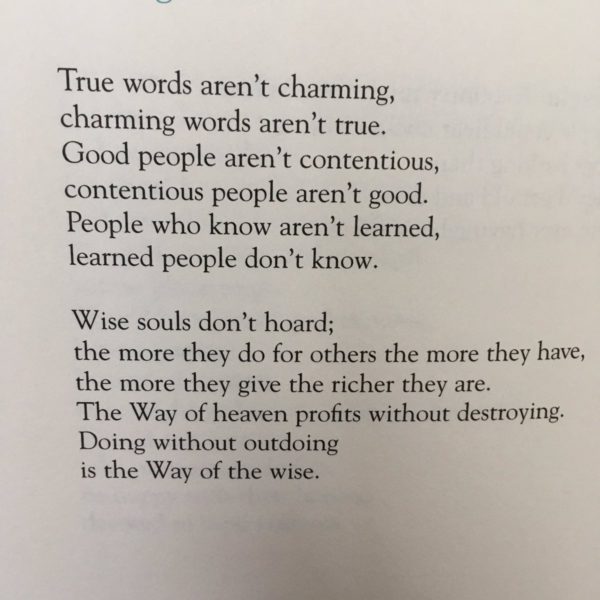

Le Guin renders the lines as delightfully folksy oppositions with rhyme and repetition. Waley piles up argumentative clauses. “One of the things I love about Lao Tzu is he is so funny,” Le Guin comments in her note,” a quality that doesn’t come through in many other translations. “He’s explaining a profound and difficult truth here, one of those counterintuitive truths that, when the mind can accept them, suddenly double the size of the universe. He goes about it with this deadpan simplicity, talking about pots.”

Such images captivated the earthy anarchist Le Guin. She drew inspiration for the title of her 1971 novel The Lathe of Heaven from Taoist philosopher Chuang Tzu, perhaps showing how she reads her own interests into a text, as all translators and interpreters inevitably do. No translation is definitive. The borrowing turned out to be an example of how even respected Chinese language scholars can misread a text and get it wrong. She found the “lathe of heaven” phrase in James Legge’s translation of Chuang Tzu, and later learned on good authority that there were no lathes in China in Chuang Tzu’s time. “Legge was a bit off on that one,” she writes in her notes.

Scholarly density does not make for perfect accuracy or a readable translation. The versions of Legge and several others were “so obscure as to make me feel the book must be beyond Western comprehension,” writes Le Guin. But as the Tao Te Ching announces at the outset: it offers a Way beyond language. In Legge’s first few lines:

The Tao that can be trodden is not the enduring and

unchanging Tao. The name that can be named is not the enduring and

unchanging name.

Here is how Le Guin welcomes readers to the Tao — noting that “a satisfactory translation of this chapter is, I believe, perfectly impossible — in the first poem she titles “Taoing”:

The way you can go

isn’t the real way.

The name you can say

isn’t the real name.Heaven and earth

begin in the unnamed:

name’s the mother

of the ten thousand things.So the unwanting soul

sees what’s hidden,

and the ever-wanting soul

sees only what it wants.Two things, one origin,

but different in name,

whose identity is mystery.

Mystery of all mysteries!

The door to the hidden.

All images of the text courtesy of Austin Kleon.

Related Content:

Ursula K. Le Guin Names the Books She Likes and Wants You to Read

Ursula K. Le Guin’s Daily Routine: The Discipline That Fueled Her Imagination

Ursula K. Le Guin Stamp Getting Released by the US Postal Service

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Ursula K. Le Guin’s Tao Te Ching: How the Sci-Fi Legend Created a Landmark Rendition of the Taoist Classic (1997) is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/2PtBiLY

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment