As an exercise draw a composition of fear or sadness, or great sorrow, quite simply, do not bother about details now, but in a few lines tell your story. Then show it to any one of your friends, or family, or fellow students, and ask them if they can tell you what it is you meant to portray. You will soon get to know how to make it tell its tale.

– Pamela Colman-Smith, “Should the Art Student Think?” July, 1908

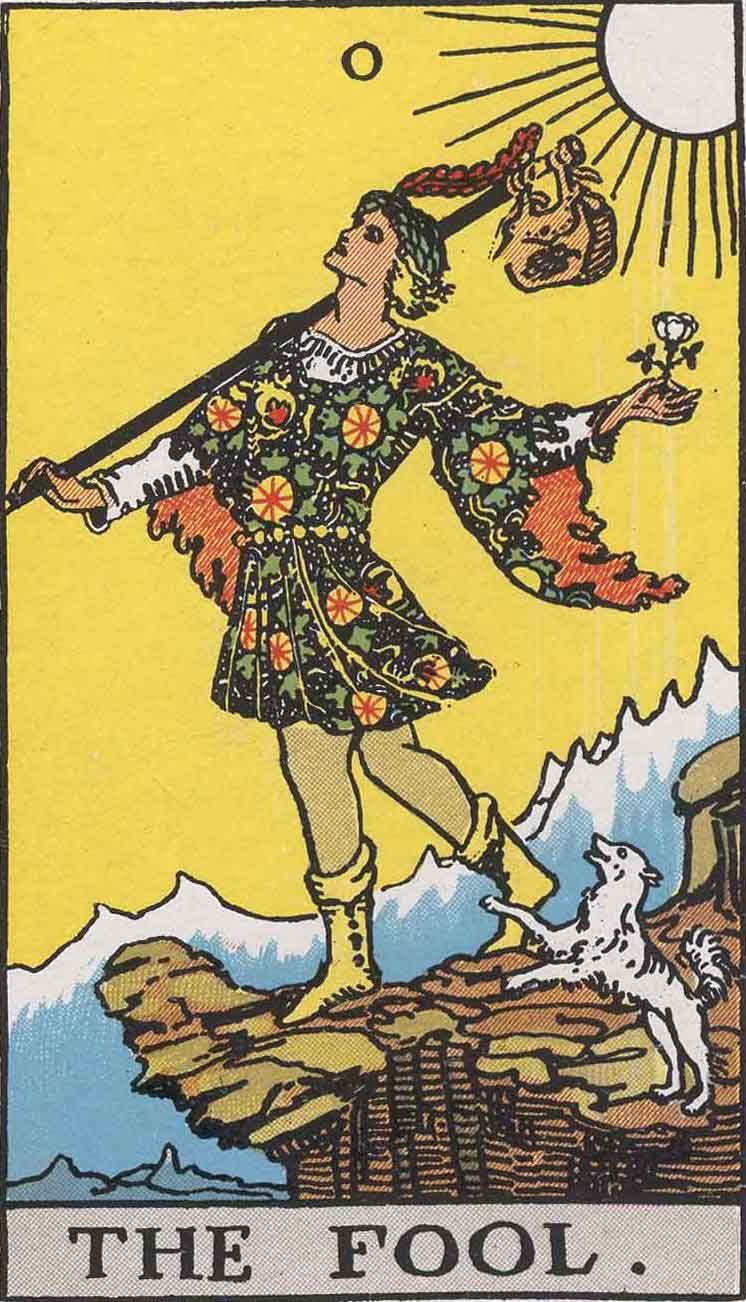

A year after Arts and Crafts movement magazine The Craftsman published illustrator Pamela Colman-Smith’s essay excerpted above, she spent six months creating what would become the world’s most popular tarot deck. Her graphic interpretations of such cards as The Magician, The Tower, and The Hanged Man helped readers to get a handle on the story of every newly dealt spread.

Colman-Smith—known to friends as “Pixie”—was commissioned by occult scholar and author Arthur E. Waite, a fellow member of the British occult society the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, to illustrate a pack of tarot cards.

In a humorous letter to her eventual champion, photographer Alfred Stieglitz, Colman-Smith (1878 – 1951) described her 80 tarot paintings as “a big job for very little cash,” though she betrayed a touch of genuine excitement that they would be “printed in color by lithography… probably very badly.”

Although Waite had some specific visual ideas with regard to the “astrological significance” of various cards, Colman-Smith enjoyed a lot of creative leeway, particularly when it came to the Minor Arcana or pip cards.

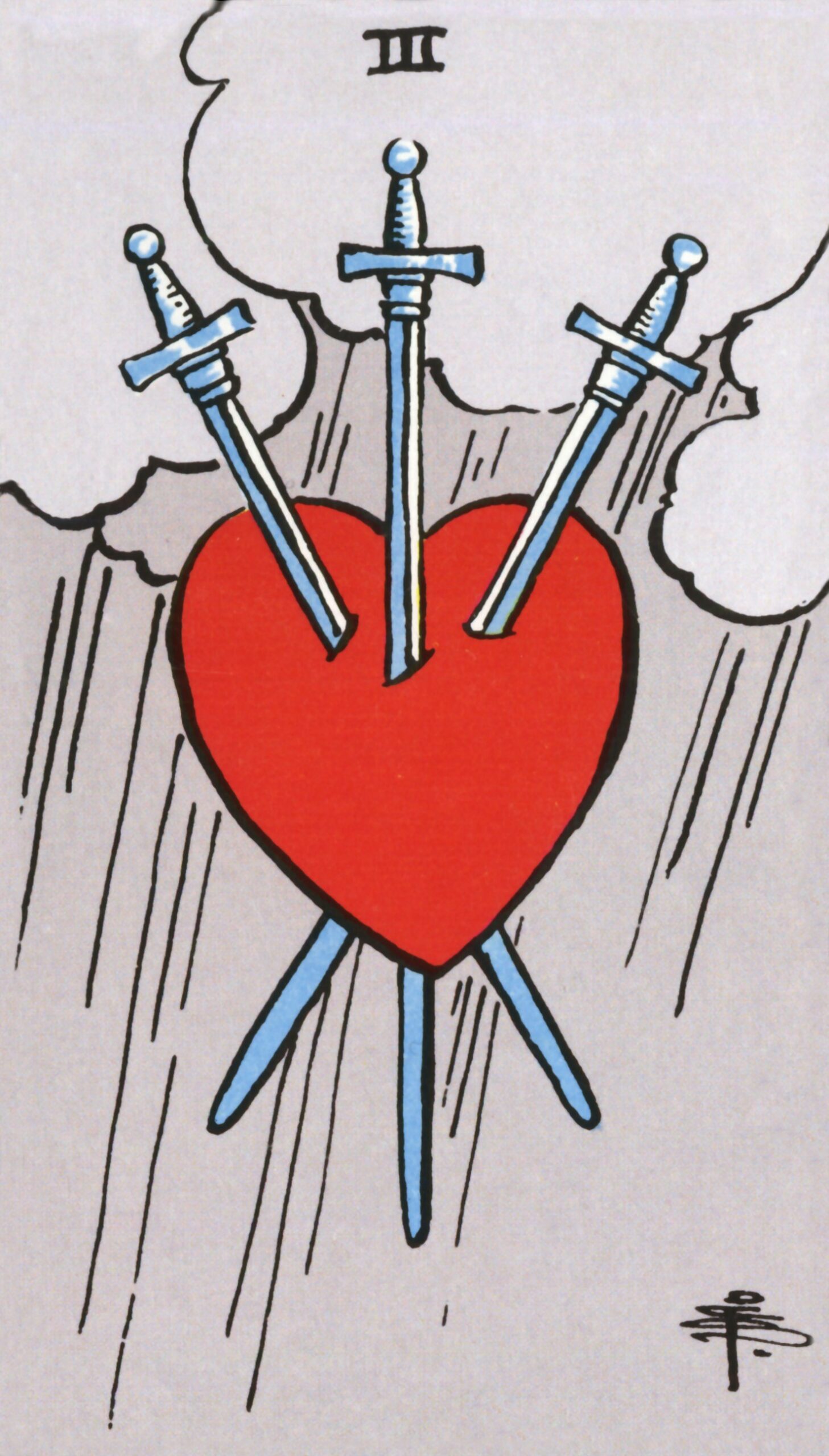

These 56 numbered cards are divided into suits—wands, cups, swords and pentacles. Prior to Colman-Smith’s contribution, the only example of a fully illustrated Minor Arcana was to be found in the earliest surviving deck, the Sola Busca which dates to the early 1490s. A few of her Minor Arcana cards, notably 3 of Swords and 10 of Wands, make overt reference to that deck, which she likely encountered on a research expedition to the British Museum.

Mostly the images were of Colman-Smith’s own invention, informed by her sound-color synesthesia and the classical music she listened to while working. Her early experience in a touring theater company helped her to convey meaning through costume and physical attitude.

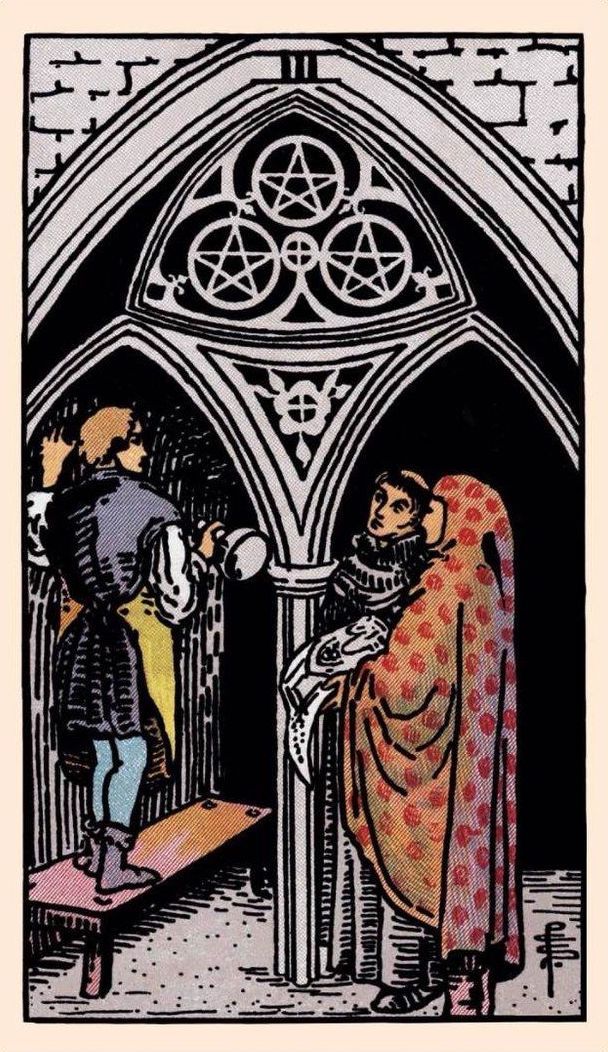

Here are Pacific Northwest witch and tarot practitioner Moe Bowstern‘s thoughts on Smith’s Three of Pentacles:

Pentacles are the suit of Earth, representative of structure and foundation. Colman-Smith’s theater-influenced designs here identify the occupations of three figures standing in an apse of what appears to be a cathedral: a carpenter with tools in hand; an architect showing plans to the group; a tonsured monk, clearly the steward of the building project.

The overall impression is one of building something together that is much bigger than any individual and which may outlast any individual life. The collaboration is rooted in the hands-on material work of foundation building, requiring many viewpoints.

A special Pixie Smith touch is the physical elevation of the carpenter, who would have been placed on the lowest rung of medieval society hierarchies. Smith has him on a bench, showing the importance of getting hands on with the project.

For years, Colman-Smith’s cards were referred to as the Rider-Waite Tarot Deck. This gave a nod to publisher William Rider & Son, while neglecting to credit the artist responsible for the distinctive gouache illustrations. It continues to be sold under that banner, but lately, tarot enthusiasts have taken to personally amending the name to the Rider Waite Smith (RWS) or Waite Smith (WS) deck out of respect for its previously unheralded co-creator.

While Colman-Smith is best remembered for her tarot imagery, she was also a celebrated storyteller, illustrator of children’s books and a collection of Jamaican folk tales, creator of elaborate toy theater pieces, and maker of images on behalf of women’s suffrage and the war effort during WWII.

Outside of some early adventures in a traveling theater, and friendships with Stieglitz, author Bram Stoker, actress Ellen Terry, and poet William Butler Yeats, certain details of her personal life—namely her race and sexual orientation—are difficult to divine. It’s not for lack of interest. She is the focus of several biographies and an increasing number of blog posts.

It’s sad, but not a total shocker, to learn that this interesting, multi-talented woman died in poverty in 1951. Her paintings and drawings were auctioned off, with the proceeds going toward her debts. Her death certificate listed her occupation not as artist but as “Spinster of Independent Means.” Lacking funds for a headstone, she was buried in an unmarked grave.

Explore more of Pamela “Pixie” Colman-Smith’s illustrations and read some of her letters to Alfred Stieglitz at Yale University’s Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library’s collection.

Related Content:

Salvador Dalí’s Tarot Cards Get Re-Issued: The Occult Meets Surrealism in a Classic Tarot Card Deck

Carl Jung: Tarot Cards Provide Doorways to the Unconscious, and Maybe a Way to Predict the Future

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

Meet the Forgotten Female Artist Behind the World’s Most Popular Tarot Deck (1909) is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/3lZZbXB

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment