17-Year-Old Adeline Harris Creates a Quilt Collecting 360 Signatures of the Most Famous People of the 19th Century: Lincoln, Dickens, Emerson & More (1863)

These days, anyone can reach out to hundreds of celebrities, artists, writers, major heads of state, etc., on social media (or to the interns and assistants who run their accounts). Instantaneous connection also means hundreds of near-instantaneous comments in near-real time. It can occasionally mean near-instantaneous influencer fame. For 17-year-old Adeline Harris, it would take seven years or so to get in touch with 360 of the biggest names in literature, politics, philosophy, science, and other fields of her time. Given that she started in 1856, that’s a somewhat extraordinary feat. It’s only one impressive feature of her Tumbling Block with Signatures Quilt, mostly completed sometime in 1863.

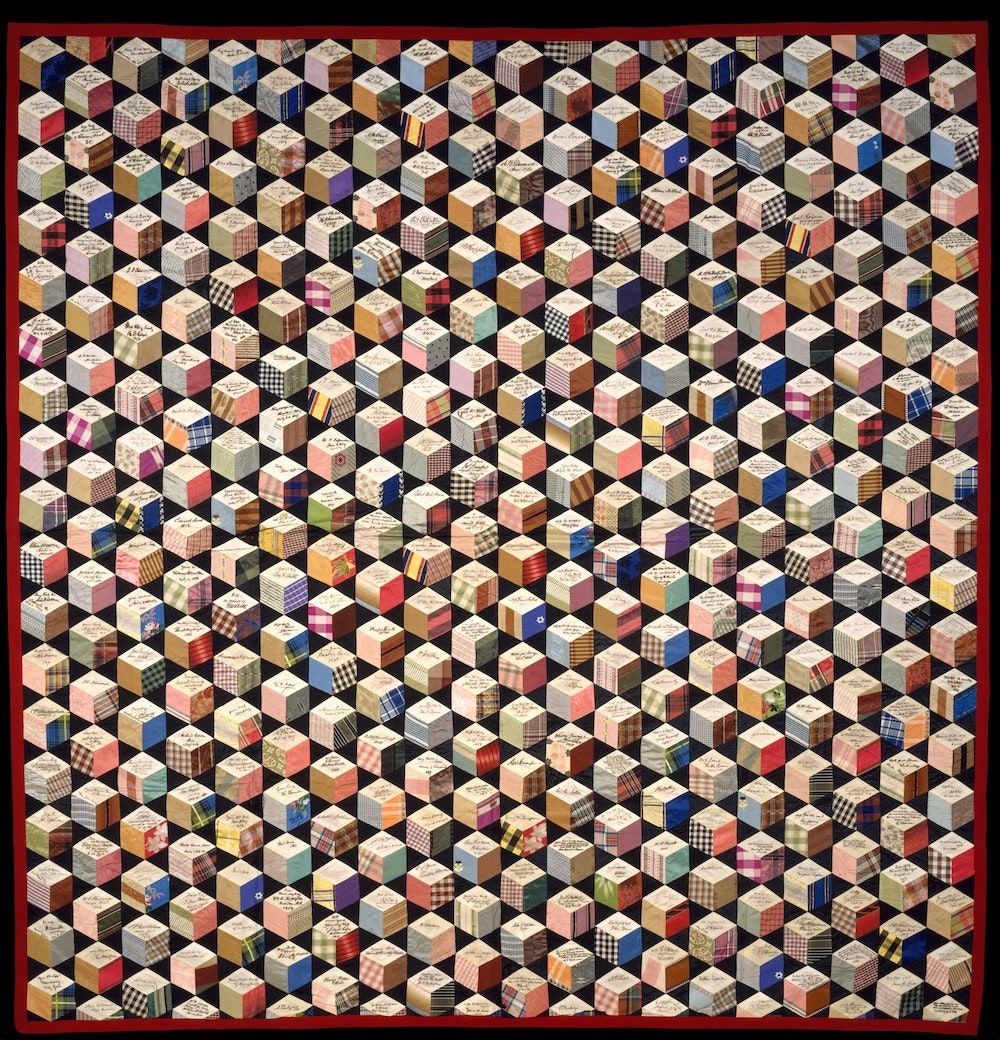

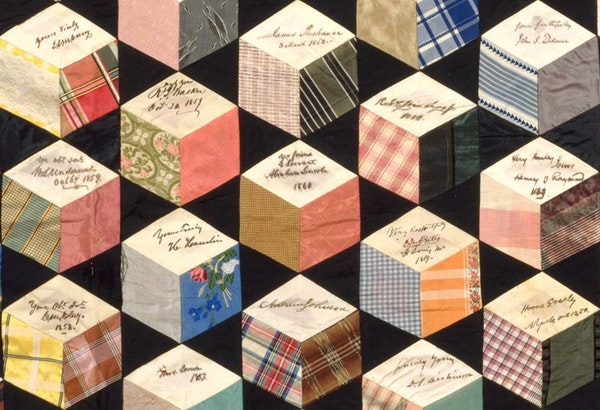

Harris’ quiltmaking project uses a “tumbling blocks pattern,” notes The History Blog, “characterized by a trompe l’oeil that gives it 3D cube effect. [She] showcased exceptional skill and mastery in her needlework and fabric choice, emphasizing the 3D effect with her arrangement of the varied patterns of silk pieces.”

The signatures on the white diamonds atop each “tumbling block” were mailed to Harris by request from a “who’s who” of mid-19th century luminaries, including “an astonishing eight presidents of the United States (Martin Van Buren, John Tyler, Millard Fillmore, Franklin Pierce, James Buchanan, Abraham Lincoln, Andrew Johnson, Ulysses S. Grant).”

The quilt also contains the signatures of Union generals, congressmen, journalists, academics, clergymen. Famous names include Samuel Morse, Horace Greeley, Washington Irving, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Jacob Grimm, Alexander von Humboldt, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Julia Ward Howe, Harriet Beecher Stowe, William Cullen Bryant, Alexandre Dumas, Oliver Wendell Holmes, William Makepeace Thackeray, and Charles Dickens. She placed the names in categories dividing the signatories by profession.

The full list “is nothing short of phenomenal,” the Public Domain Review writes, adding that “according to her grand-daughter the Lincoln signature was, due to a family connection, actually acquired in person, and Adeline was meant to have even danced with Lincoln at his inauguration ball.” Harris — later Adeline Harris Sears — came from a wealthy Rhode Island textile mill family and married a prominent clergyman. She spent most of her life in the state, and mailed most of her signature requests rather than delivering them firsthand.

Signature quilts were not new; they had been sewn for years to mark family occasions and other events. But never had they been a means of celebrity autograph-hunting, nor been created by a single individual. Collecting autographs, however, was quite popular. “Adeline’s taste for autographs… betrays her romantic nature,” writes Metropolitan Museum of Art curator Amelia Peck. “Among a certain segment of the population, it was believed that a person’s signature revealed significant aspects of his or her personality.”

It’s hard not to see the seeds of our contemporary culture in the consumption of celebrity autographs Peck describes: “By owning a signature of an illustrious person, one could learn about the characteristics that made him or her great and emulate those traits.” This mania for autographs “paralleled the nineteenth-century fascination with other types of pseudoscientific personality discovery, such as phrenology.” There were deep, mystical meanings in Adeline’s quilt, wrote editor Sarah Hale, who also donated a signature. In her 1868 book Manners, Happy Homes and Good Society All the Year Round, Hale explained what made the quilt a masterpiece:

In short, we think this autograph bedquilt may be called a very wonderful invention in the way of needlework. The mere mechanical part, the number of small pieces, stitches neatly taken and accurately ordered; the arranging properly and joining nicely 2780 delicate bits of various beautiful and costly fabrics, is a task that would require no small share of resolution, patience, firmness, and perseverance. Then comes the intellectual part, the taste to assort colors and to make the appearance what it ought to be, where so many hundreds of shades are to be matched and suited to each other. After that we rise to the moral, when human deeds are to live in names, the consideration of the celebrities, who are to be placed each, the centre of his or her own circle! To do this well requires a knowledge of books and life, and an instinctive sense of the fitness of things, so as to assign each name its suitable place in this galaxy of stars or diamonds.

See more close-ups of the quilt at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, who hold this one-of-a-kind work of signatory fabric art in their collections.

Related Content:

Too Big for Any Museum, AIDS Quilt Goes Digital Thanks to Microsoft

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness.

17-Year-Old Adeline Harris Creates a Quilt Collecting 360 Signatures of the Most Famous People of the 19th Century: Lincoln, Dickens, Emerson & More (1863) is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/2OyFQRb

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment