The Bayeux Tapestry Gets Digitized: View the Medieval Tapestry in High Resolution, Down to the Individual Thread

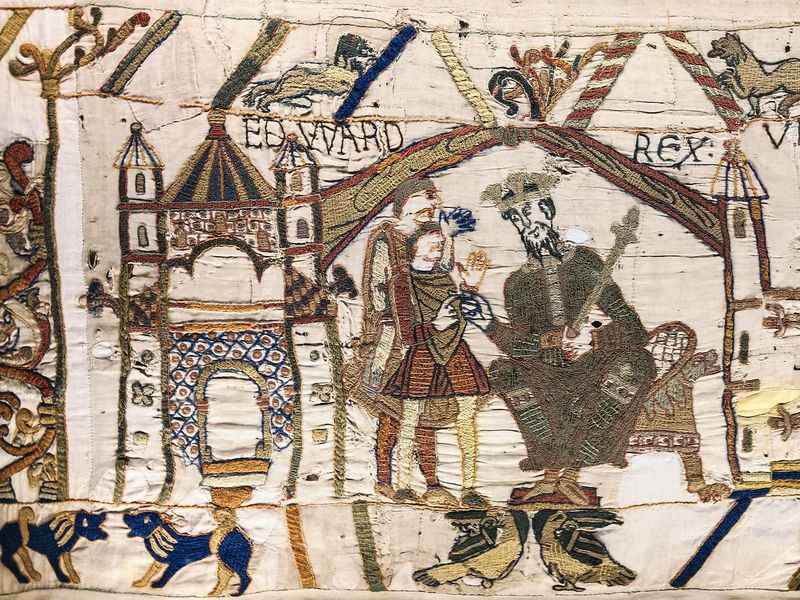

The Bayeux Tapestry, one of the most famous artifacts of its kind, isn’t actually a tapestry. Technically, because the images it bears are embroidered onto the cloth rather than woven into it, we should call it the Bayeux Embroidery. To quibble over a matter like this rather misses the point — but then, so does taking too literally the story it tells in colored yarn over its 224-foot length. Commissioned, historians believe, as an apologia for the Norman conquest of England in 1066, this elaborate work of narrative visual art conveys events with a certain slant. But in so doing, the Bayeux’s 75 dramatic, bloody, ribald, and sometimes mysterious episodes also capture how people and things (and even Halley’s Comet) looked in medieval Europe.

It does this in great, if stylized detail, at which you can get a closer look than has ever before been available to the public at the Bayeux Museum’s web site. The museum “worked with teams from the University of Caen Normandie to digitize high-resolution images of the tapestry, which were taken in 2017,” says Medievalists.net.

“A simple interface was created to access the digital version, which allows users to zoom in and explore it in great detail with access to Latin translations in French and English.” Made of 2.6 billion pixels (which brings it to eight gigabytes in size), the online Bayeux Tapestry lets us zoom in so far as to examine its individual threads — the same level at which it was inspected in real life earlier last year in anticipation of its next restoration.

“A team of eight restorers, all specialists in antique textiles, carried out the detailed inspection in January 2020, a period when the museum was closed to visitors,” says Medievalists.net. “Among their findings were that the tapestry has 24,204 stains, 16,445 wrinkles, 9,646 gaps in the cloth or the embroidery, 30 non-stabilized tears, and significant weakening in the first few metres of the work.” (Notably, the colors applied in a 19th-century restoration have faded much more than the vegetable dyes used in the original.) Though currently a bit rough around the edges, the Bayeux Tapestry looks pretty good for its 950 or so years, as any of us can now look more than closely enough to see for ourselves. This is a credit to its makers — whose identities, for all the scrutiny performed on the work itself, may remain forever unknown. Explore the high-resolution scan of the Tapestry here.

via Smithsonian Magazine and Medievalists.net

Related Content:

The Animated Bayeux Tapestry: A Novel Way of Recounting The Battle of Hastings (1066)

Construct Your Own Bayeux Tapestry with This Free Online App

How the Ornate Tapestries from the Age of Louis XIV Were Made (and Are Still Made Today)

160,000 Pages of Glorious Medieval Manuscripts Digitized: Visit the Bibliotheca Philadelphiensis

Why Knights Fought Snails in Illuminated Medieval Manuscripts

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

The Bayeux Tapestry Gets Digitized: View the Medieval Tapestry in High Resolution, Down to the Individual Thread is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/38N13NS

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment