When R.E.M.’s Michael Stipe Created the Lyrics for “The Voice of Harold” by Riffing on the Liner Notes of an Old Gospel Album (1983)

R.E.M. is one of those bands that just thinking about can send me into a reverie of memories of the rooms of friends with whom I listened to “Pretty Persuasion,” “Rockville,” and the poetry of “7 Chinese Bros.”—one of Michael Stipe’s early, incomprehensible songs, like “Swan Swan H,” whose cryptic lyrics one must seemingly take on faith. The song must mean something, after all, to Stipe. Maybe the mystery of who, exactly, the “seven Chinese brothers swallowing the ocean” were to him would be revealed someday in an interview or stray reference in a biography….

Now that we live in an age of instant information gratification, we can skip the years of wonder and find the answer right away: the song was partly inspired, we learn at Songfacts, by a 1938 children’s book called The Five Chinese Brothers, based on a traditional folk tale of young brothers with supernatural powers. (It’s also partly a tribute to photographer Carol Levy, a friend who died in a car crash before the recording of Reckoning.) Needing another syllable, maybe, Stipe changed the number to seven, an oddly prophetic move given that a new version of the story, published ten years later, also featured seven brothers.

The reference shows how many great songwriters work: picking at bits and pieces from their memories and whatever captivating text happens to be laying around…. And Stipe is one of those singers, like Elton John, who can sell any line, no matter how obscure or absurd.

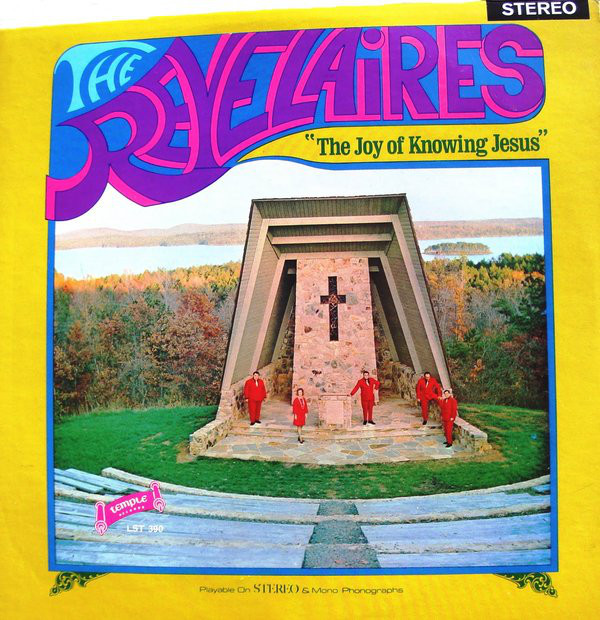

In early songs, especially, he showed an uncanny ability to invest incantatory combinations of words with haunting pathos and urgency. He could sing from the phone book or the back of a cereal box and make it compelling. In fact, the story of “7 Chinese Bros.” involves an almost similar feat in the form of “Voice of Harold,” familiar to fans as the B-side to “So. Central Rain” and part of the 1987 odds and ends collection Dead Letter Office. What possible explanation could there be for these impassioned, non sequitur gospel lyrics, sung to the tune of… “7 Chinese Bros.”?

Was Stipe a secret Evangelist, hoping to win converts by extolling “the pure tenor quality of the voice of Harold Montgomery”? More teasingly vague themes emerge, along with references to figures like the Reverend Bill Funderburk, Charles Surratt, John Barbee, and Rhonda Montgomery (“That’s Rhonda! An artist!”). Instead of “Seven Chinese brothers swallowing the ocean,” the chorus introduces us to “The Revelaires, A must / The Revelaires / A must.” If you’re one of those who heard this song and thought, “What…?”, you can wonder no more.

The explanation comes to us from a 2009 interview producer Don Dixon gave to Uncut magazine. (For some reason, Dixon refers to “7 Chinese Bros.” as “7 Chinese Blues,” never a title of the song). The story begins with Stipe feeling down in the dumps in a stairwell outfitted as a lounge for him in the studio.

We were working on the vocal for "7 Chinese Blues," but Michael just wasn't into it. He was down in his stairwell. I hit the talk-back to let him know I was coming through to make an adjustment... This was just an excuse to take a look at him, see if I could loosen him up a little. While I was in the attic, I'd noticed a stack of old records that had been taken up there to die, local R&B and gospel stuff mostly. I grabbed the one off the top (a gospel record entitled The Joy of Knowing Jesus by the Revelaires) and as I passed Michael on the way to the Control Room, I tossed it down to him. I thought he might be amused. When I fired up the tape a few seconds later, Michael was singing, but not the lyrics to "7 Chinese Blues." He was singing the liner notes to the LP I'd tossed him. When Michael began to sing these liner notes, he was much louder than he'd been earlier and it took a few seconds for me to realise what was going on and adjust the levels. He made it all the way through the song, working in every word on the back of that album! I rewound the tape, we had a chuckle and proceeded to sing the beautiful one-take vocal of the real words that you hear on Reckoning. He seemed more confident after that day.

Stipe didn’t just sing the words from the back of the album, he improvised cut-ups as he went, re-arranging phrases to fit the meter of the original song. “Voice of Harold” became a fan favorite for much the same reason as “7 Chinese Bros.” and “Swan Swan H”—it seemed to hide a mystery in plain view, its impassioned delivery at odds with its nonsensical narrative. Released after Reckoning, it turns a spontaneous motivational tool during the making of the album into a creation all its own.

Jim Connelly explores the relationship between “7 Chinese Bros.” and “Voice of Harold” even further in a post at Medialoper, pointing to what’s so “chill-inducing” about the latter. They may be found words, serendipitously picked up and put together on the spot, but in Stipe’s voice we can tell that “He’s real. He means it,” whatever the hell it is. See a video of "Voice of Harold" with lyrics, at the top, and follow along with the liner notes on the back of Revelaires' gospel album The Joy of Knowing Jesus just above.

Related Content:

“It’s the End of the World as We Know It,” Michael Stipe Proclaims Again, and He Still Feels Fine

Why R.E.M.’s 1991 Out of Time May Be the “Most Politically Important Album” Ever

R.E.M.’s “Losing My Religion” Reworked from Minor to Major Scale

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

When R.E.M.’s Michael Stipe Created the Lyrics for “The Voice of Harold” by Riffing on the Liner Notes of an Old Gospel Album (1983) is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/3jgbr47

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment