Understanding Chris Marker’s Radical Sci-Fi Film La Jetée: A Study Guide Distributed to High Schools in the 1970s

Pop quiz, hot shot. World War III has devastated civilization. As a prisoner of survivors living beneath the ruins of Paris, you're made to go travel back in time, to the era of your own childhood, in order to secure aid for the present from the past. What do you do? You probably never faced this question in school — unless you were in one of the classrooms of the 1970s that received the study guide for Chris Marker's La Jetée. Like the innovative 1962 science-fiction short itself, this educational pamphlet was distributed (and recently tweeted out again) by Janus Films, the company that first brought to American audiences the work of auteurs like Ingmar Bergman, Federico Fellini, and Akira Kurosawa.

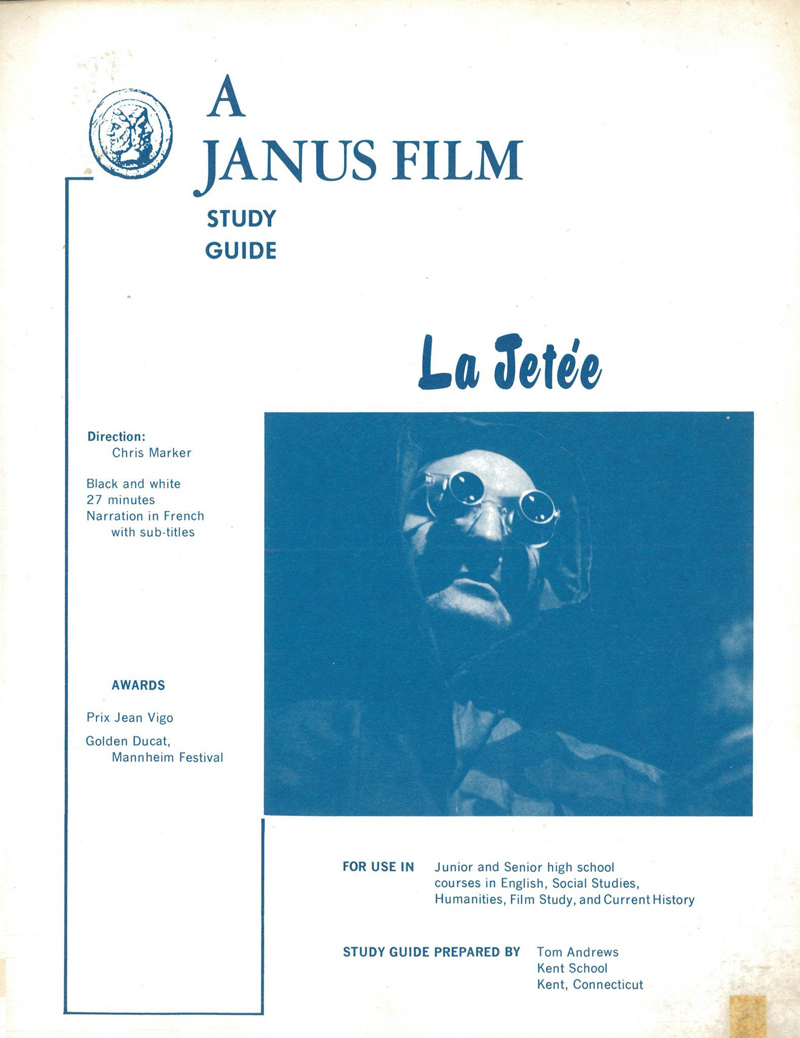

Written by Connecticut prep-school teacher Tom Andrews, this study guide describes La Jetée as "a brilliant mixture of fantasy and pseudo-scientific romance" that "explores new dramatic territory and forms, and rushes with a stunning logic and a powerful impact to its shocking climax."

The film does all this "almost entirely in still photographs, their static state corresponding to the stratification of memory." More practically speaking, at "twenty-seven minutes in length, La Jetée is an ideal class-period vehicle" that "can help students speculate on the awesome potential of life as it may exist after a third world war" as well as "man's inhumanity to man, not only as it may occur in the future, but as it already has occurred in our past."

"Why do you suppose Marker filmed La Jetée in still photographs? What significance does the one moment of live action have?" "How does Marker's concept of time and space compare with that of H.G. Wells in the latter's novel, The Time Machine?" "If the man of this story has helped his captors to perfect the technique of time travel, why do they wish to liquidate him?" These and other suggested discussion questions appear at the end of the study guide, all of whose pages you can read at Socks. It was produced for Films for Now and The Human Condition, "two repertories for high school assemblies and group discussions" based on Janus' formidable cinema library. (François Truffaut's The 400 Blows also looks to have been among their educational offerings.) You can see further analysis of La Jetée in A.O. Scott's New York Times Critics' Picks video, as well as the Criterion Collection video essay Echo Chamber: Listening to La Jetée.

Much later, in the mid-1990s, Terry Gilliam would pay tribute with his Hollywood homage 12 Monkeys, and Marker himself still had many films to make, including his second masterpiece, the equally unconventional Sans Soleil. But at time of this study guide's publication, La Jetée's considerable influence had only just begun to manifest. It was around then that pioneering cyberpunk novelist William Gibson viewed the film in college. "I left the lecture hall where it had been screened in an altered state, profoundly alone," he later remembered. "My sense of what science fiction could be had been permanently altered." Perhaps his instructor heeded Andrews' advice that "teachers would probably do better not to 'prepare' their students for viewing this film." Not that anyone, in the 58 years of the film's existence, has anyone ever truly been prepared for their first viewing of La Jetée.

Related Content:

Petite Planète: Discover Chris Marker’s Influential 1950s Travel Photobook Series

A Concise Breakdown of How Time Travel Works in Popular Movies, Books & TV Shows

Free MIT Course Teaches You to Watch Movies Like a Critic: Watch Lectures from The Film Experience

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, on Facebook, or on Instagram.

Understanding Chris Marker’s Radical Sci-Fi Film La Jetée: A Study Guide Distributed to High Schools in the 1970s is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/3kKhs9y

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment