Let’s say you go home for the holidays. Anything’s possible, who knows. It’s a wild world. Let’s say you get there and someone starts laying on you that trip about how Q Continuum said mail-in voting was orchestrated by satanic cables from Anarchist HQ. Let’s say you overhear something more down-to-earth, like how if mail-in voting happens, billions of people will vote illegally... even more people than live in the country, which is how you’ll know….

Maybe you’ll want to speak up and say, hey I know something about this topic, except then maybe you realize you don’t actually know much, but you know something ain’t right with this talk and maybe it’s probably good to have a functioning Postal Service and maybe people should be able to vote. In such situations (who can say how often these things happen), you might wish to have a little information at the ready, to educate yourself and share with others.

You might share information about how mail-in voting has been around since 1775. It has worked pretty well at scale since “about 150,000 of the 1 million Union soldiers were able to vote absentee in the 1864 presidential election in what became the first widespread use of non-in person voting in American history,” Alex Seitz-Wald explains at NBC News. Since the federal government has managed to make mail-in voting work for soldiers serving away from home for over 150 years,“it’s now easier in some ways for a Marine in Afghanistan to vote than it is for an American stuck at home during the COVID-19 lockdown.”

“Some part of the military has been voting absentee since the American Revolution,” Donald Inbody, former Navy Captain turned political science professor at Texas State University, tells NBC News. Inbody refers to one of the first documented instances, when Continental Army soldiers voted in a town meeting by proxy in New Hampshire. But history is complicated, and “mail-in voting has worked just fine so shut up" needs some nuance.

In the very same election in which 150,000 Union soldiers mailed their ballots, Lincoln urged Sherman to send troops stationed in Democratic-controlled Indiana—which had banned absentee voting—back to their home states so that they could vote. The practice has always had its vocal critics and suffered accusations of fraud from all sides, though little evidence seems to have emerged. Absentee voting helped win the Civil War, Blake Stilwell argues at Military.com, in spite of a conspiracy theory alleging fraud that might have unseated Lincoln.

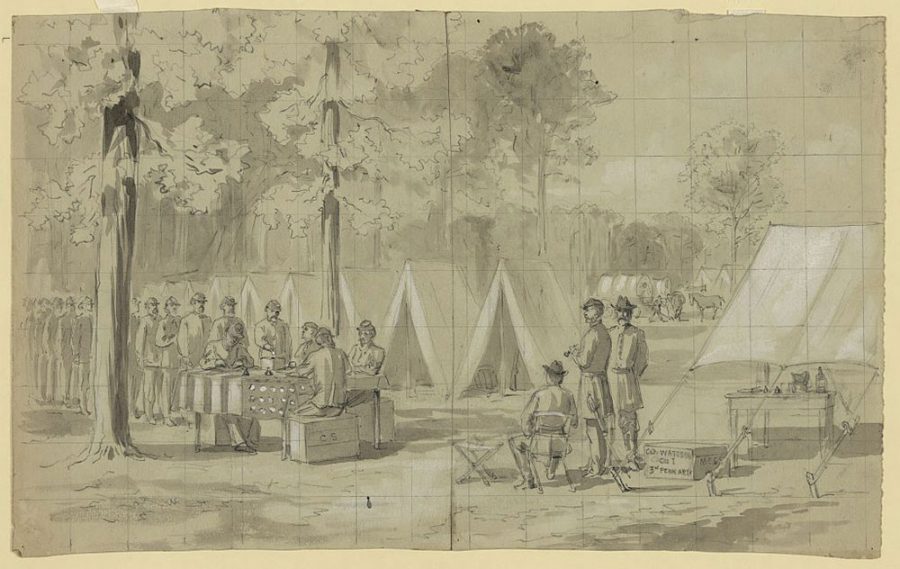

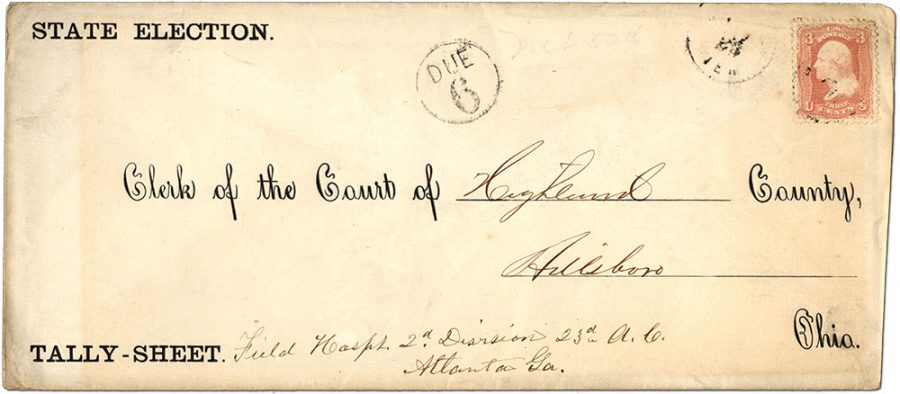

There are several remnants from the time of careful record-keeping, like the pre-printed envelope above that “contained a tally sheet of votes from the soldiers of Highland County the Field Hospital 2nd Division 23rd Army Corps,” notes the Smithsonian National Postal Museum. (The drawing at the top shows Pennsylvania soldiers voting in 1864.) And this is all fascinating stuff. But soldiers are actually absent, which is why they vote absentee, right? I mean, if you’re at home, why can’t you just go to the polling place in the global pandemic in your city that closed all the polling places?

It’s true that civilian mail-in voting often works differently from military absentee voting. While every state offers some version, some restrict it to voters temporarily out of state or suffering an illness. Currently, only “30 states have adopted ‘no-excuse absentee balloting,’ which allows anyone to request an absentee ballot,” Nina Strochlic reports at National Geographic. State laws vary further among those 30. “In 2000,” for example, “Oregon became the first state to switch to fully vote-by-mail elections." Things have rapidly changed, however. "In the face of the coronavirus pandemic, voters in every state but Mississippi and Texas were allowed to vote by mail or by absentee ballot in this year’s primaries.”

If you live in the U.S. (or outside it) and don’t know what happened next… bless you. It involves defunding the post office instead of the police.

Voting by mail has expanded to meet major crises throughout history, says Alex Keyssar, history professor at the Kennedy School of Government at Harvard. “That’s the logical trajectory” and “we are not in normal times.” If a highly infectious disease that has killed at least 200,000 Americans on top of ongoing voter suppression and an election security crisis and massive civil unrest and economic turmoil aren't reasons enough to expand the vote-by-mail franchise to every state, I couldn’t say what is.

Should only soldiers have the ability to vote easily? I imagine someone might say YES, loudly over the centerpiece, because voting is a privilege not a right!

You, empowered purveyor of accurate information, understander of absentee voting history, change-maker, will pull out your pocket Constitution and ask someone to find the word “privilege” in amendments that start with “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State,” etc. That'll show 'em. But if the gambit fails, you've still got a better understanding of why voting by mail may not be one of the signs of the end times.

Related Content:

Take The Near Impossible Literacy Test Louisiana Used to Suppress the Black Vote (1964)

Three Public Service Announcements by Frank Zappa: Vote, Brush Your Teeth, and Don’t Do Speed

Sal Khan & the Muppets’ Grover Explain the Electoral College

The Psychology That Leads People to Vote for Extremists & Autocrats: The Theory of Cognitive Closure

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Mail-In Voting Isn’t New In America; It Goes Back to the Civil War is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/2G6GZun

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment