19th-Century Japanese Woodblocks Illustrate the Lives of Western Inventors, Artists, and Scholars (1873)

For more than 200 years between the mid-17th and mid-19th century, Japan closed itself to the outside world. But when it finally opened again, it couldn't get enough of the outside world. The American Navy commodore Matthew Perry arrived with his formidable "Black Ships" in 1853, demanding that Japan engage in trade. Five years later came the Meiji Restoration, which consolidated Japan's political system under imperial rule and encouraged both industrialization and Westernization. Or rather, it encouraged the importation of Western technology and ideas for use in Japanese ways, a combination known as wakon-y?sai, meaning "Japanese spirit and Western techniques."

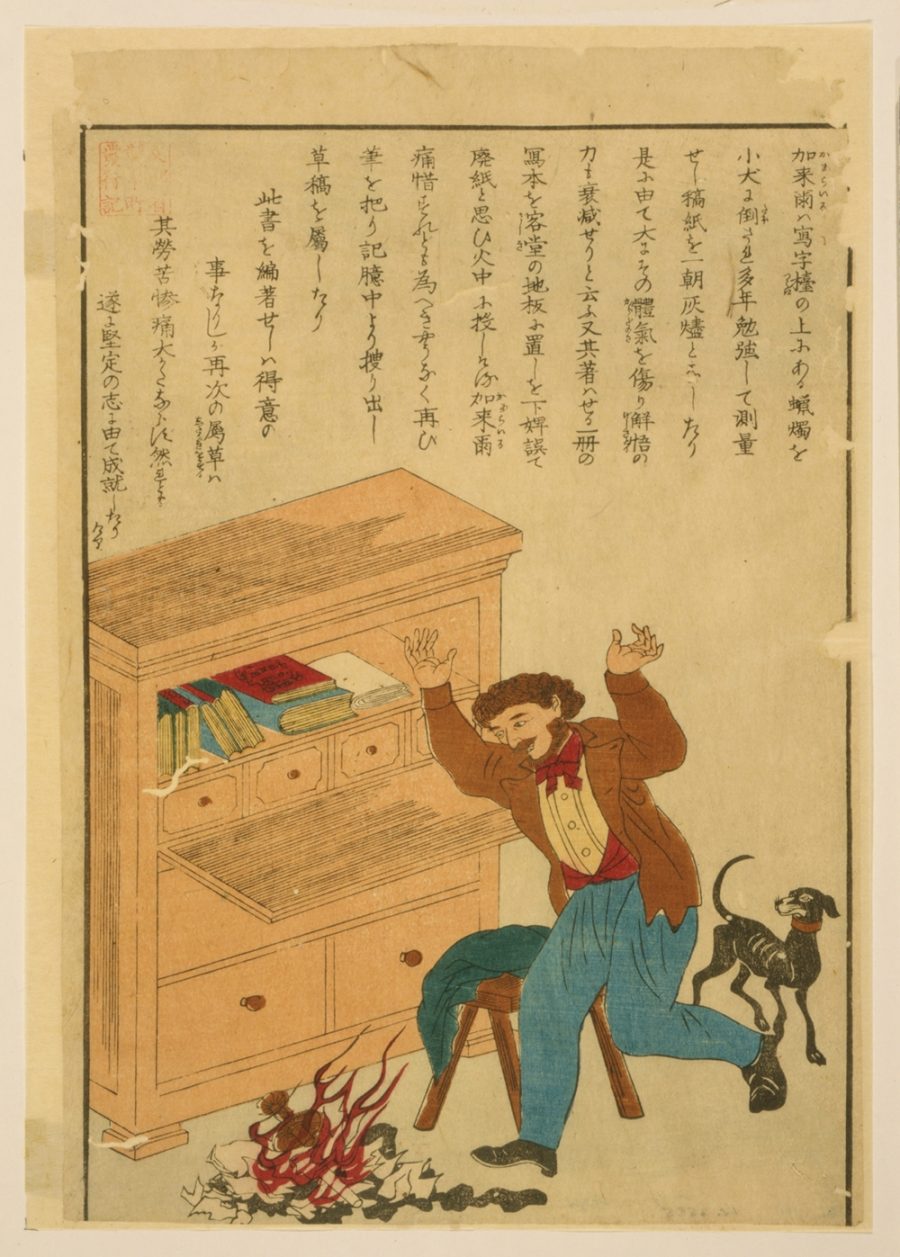

It is in the mindset of wakon-y?sai, says the Public Domain Review, that we should view these Japanese woodblock prints of Western inventors, scholars, and artists. Most likely dating from 1873 — a heady time for the mixture of Japanese spirit and Western techniques — they depict these figures facing a variety of challenges, some more plausible than others.

"The great naturalist John James Audubon battles with a mischievous rat who has eaten his work; the dog of historian and poet Thomas Carlyle has upset a lamp burning his papers; the wife of Richard Arkwright, inventor of the spinning-frame, smashes his creation; the developer of the Watt steam engine James Watt suffers the wrath of his impatient Aunt; pottery impresario Bernard Palissy has to burn his family's furniture to keep his kiln's fire going."

Commissioned by the Japanese Department of Education, these schoolbook illustrations may bring to mind the 1861 Japanese history of America previously featured on Open Culture, with its tiger-punching George Washington and serpent-slaying John Adams. But the text that accompanies these mightily struggling Western luminaries, translations of which you can find along with the images at the Public Domain Review, "paints a slightly more positive picture, revealing the moral, something akin to 'If at first you don't succeed then try again,' or 'Perseverance prospers.'" In Japan's case, perseverance would indeed make it one of the most prosperous nations in the world — if only after its defeat in World War II, by some of the very nations whose historical figures it had lionized less than a century before. Find more images at the Public Domain Review and the Library of Congress.

Related Content:

19th Century Japanese Woodblock Prints Creatively Illustrate the Inner Workings of the Human Body

Download Hundreds of 19th-Century Japanese Woodblock Prints by Masters of the Tradition

Enter a Digital Archive of 213,000+ Beautiful Japanese Woodblock Prints

The 10 Commandments of Chind?gu, the Japanese Art of Creating Unusually Useless Inventions

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, on Facebook, or on Instagram.

19th-Century Japanese Woodblocks Illustrate the Lives of Western Inventors, Artists, and Scholars (1873) is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/2ZpTkAK

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment