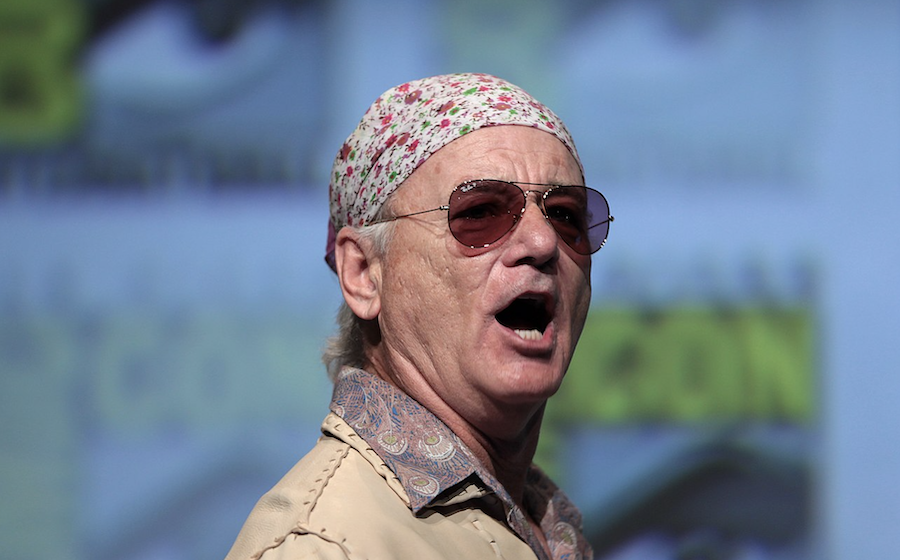

Image by Gage Skidmore, via Wikimedia Commons

"Bill Murray is to me what calculators are to math," Jason Schwartzman once said of his esteemed colleague. "I never knew math before calculators, and I never knew life before Bill Murray." Having been born in the 1980s, a decade Murray entered already well-known after three early seasons of Saturday Night Live, I could say the same. Through characters like Nick the lounge singer and half a nerd couple with Gilda Radner, Murray established himself on that show as a goofball, but a goofball of a higher order. As the 80s got into full swing, Murray got into the movies, and ever more prominent roles in the likes of Caddyshack, Stripes, and Ghostbusters assured him a permanent place in the pantheon of American comedy.

For those who cared to look, there has long been evidence of concentrated thought and feeling behind the deadpan impulsiveness of Murray's onscreen persona: his supporting turn as Dustin Hoffman's lemon-eating playwright roommate in Tootsie, his passion-project adaptation of Somerset Maugham's The Razor's Edge, his post-Ghostbusters escape to the Sorbonne.

It was in Paris that Murray studied the work of the Greco-Armenian Sufi mystic G.I. Gurdjieff, who describes a path to enlightenment called "the way of the sly man," one who makes maximum use of "the world, the self, and the self that is observing everything." This concept, according to the Wisecrack video above, has become integral to Murray's distinctive way of not just acting, but being.

That counts as just one of the theories advanced over the decades to explain the curious phenomenon of Bill Murray. The man has also been called upon to explain it himself now and again, as when an interviewer at the Toronto International Film Festival asked what it feels like to be him. His response takes the audience into a guided meditation meant to make everyone listening understand how it feels to be themselves, right here, right now.

Maintaining this sense of the moment, as Murray later explained to Charlie Rose, is one of the goals of his own life — and presumably not an easy goal to achieve for someone who's been so famous for so long, a condition he addresses in the 1988 interview animated for Blank on Blank below. "I'm just an obnoxious guy who can make it appear charming," he says in summation of his appeal. "That's what they pay me to do."

That same year, they paid him $6 million for his role in Scrooged (playing, incidentally, the most obnoxious character of his career). He'd already been cautioned against the dangers of such rapidly acquired wealth and fame by the fate of his fellow Chicagoan and SNL alumnus John Belushi, who by that time had already been dead for five years. Murray had also, he says, undergone a "spiritual change" that showed him "there was some other life to live. It changed the way that I worked," giving everything "a different presence, a different tension." Onscreen, this change culminated in the roles he took on after putting broad comedies behind him beginning with 1999's Rushmore, the breakout feature by an up-and-coming director named Wes Anderson.

Casting Murray opposite the teenage Schwartzman, Rushmore showed that he could be more affecting — and indeed funnier — in minor emotional keys. A few years later, Sofia Coppola's Lost in Translation took him to Japan, where he drew an Academy Award nomination with his performance from the depths of cultural and personal disorientation. Today, on Murray's 70th birthday, his fans impatiently await his appearances in Anderson's The Paris Dispatch and Coppola's On the Rocks, both of which come out next month. Having long since become an institution (albeit an insistently unconventional and unpredictable one) unto himself, Murray can surely look to the heavens and say what, with uncharacteristic earnestness, he told his SNL audience he wanted to say 33 years ago: "Dad, I did it."

Related Content:

Bill Murray Explains How a 19th-Century Painting Saved His Life

Art Exhibit on Bill Murray Opens in the UK

Watch Bill Murray Perform a Satirical Anti-Technology Rant (1982)

Watch Dan Aykroyd & Bill Murray Goof Off in a Newly Unearthed Ghostbusters Promotional Film (1984)

Listen to Bill Murray Lead a Guided Meditation on How It Feels to Be Bill Murray

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, on Facebook, or on Instagram.

The Life, Work & Philosophy of Bill Murray: Happy 70th Birthday to an American Comedy Icon is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/2ZVaExS

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment