As you know if you’re a reader of this site, there are vast, interactive (and free!) scholarly databases online collecting just about every kind of artifact, from Bibles to bird calls, and yes, there are a significant number of cookbooks online, too. But proper searchable, historical databases of cookbooks seem to have appeared only lately. To my mind these might have been some of the first things to become available. How important is eating, after all, to virtually every part of our lives? The fact is, however, that scholars of food have had to invent the discipline largely from scratch.

“Western scholars had a bias against studying sensual experience,” writes Reina Gattuso at Atlas Obscura, “the relic of an Enlightenment-era hierarchy that considered taste, touch, and flavor taboo topics for sober academic inquiry. ‘It’s the baser sense,’ says Cathy Kaufman, a professor of food studies at the New School.” Kaufman sits on the board of The Sifter, a new massive, multi-lingual online database of historical recipe books. Another board member, sculptor Joe Wheaton, puts things more directly: “Food history has been a bit of an embarrassment to a lot of academics, because it involves women in the kitchen.”

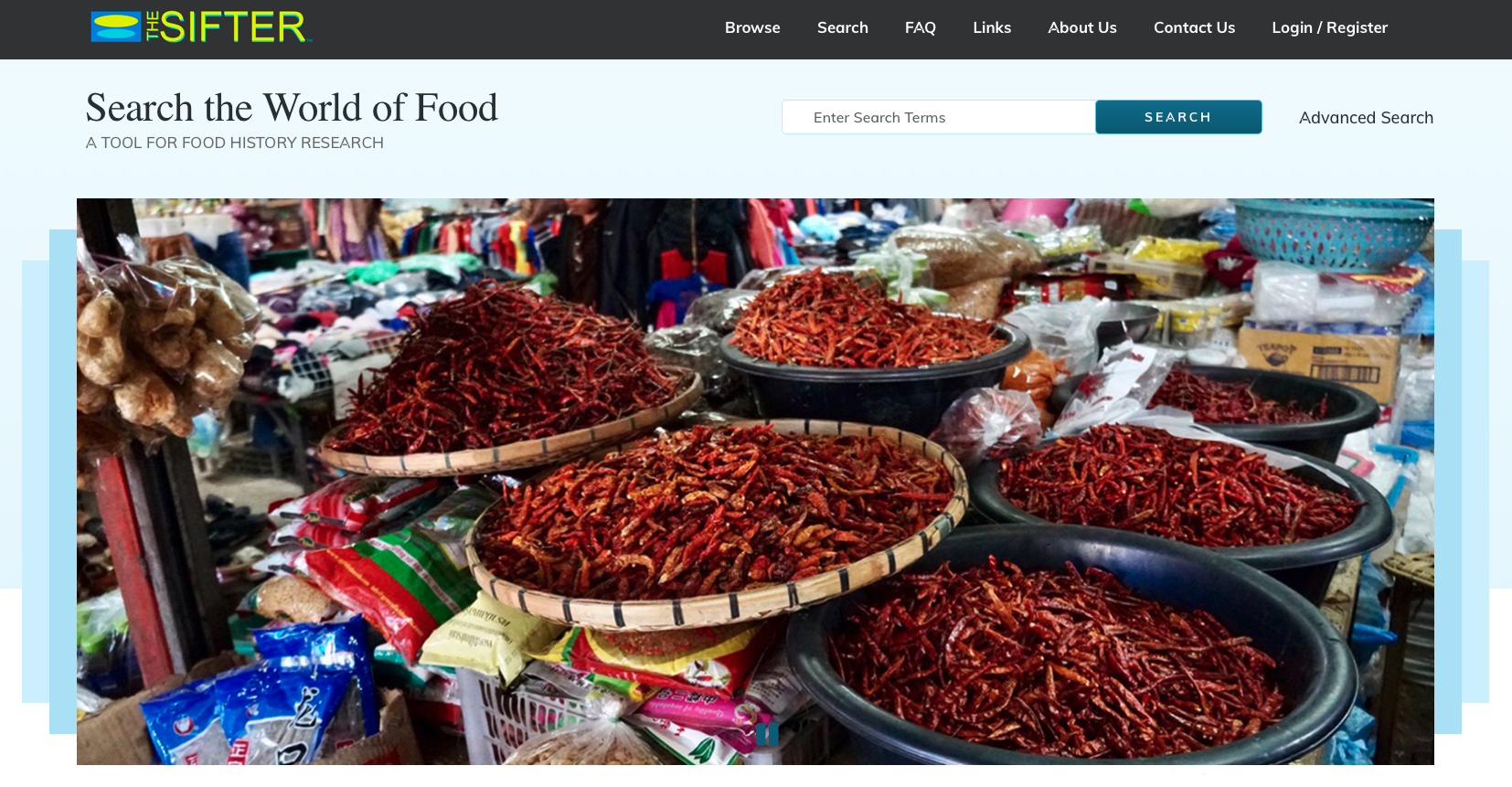

Luckily for food scholars, the situation has changed dramatically. There are now over 2,000 historical Mexican cookbooks of all kinds online at the University of Texas San Antonio, for example. (The UTSA is busy curating and translating hundreds of those recipes into English for what they call a “series of mini-cookbooks.”) And scholars of food history may have to be pulled away by force from The Sifter, a vast, ever-expanding Wikipedia-like archive of food research.

The database collects “over 5,000 authors and 5,000 works with details about the authors and about the contents of the works,” the site explains. “The central documents are cookbooks and other writings related to getting, preparing, and consuming food, and the activities associated with them, as well as writings about cultural and moral attitudes.” Like Wikipedia, users are invited to submit their own data, which can be edited by other users. Unlike the public encyclopedia, which we know has serious flaws, The Sifter is overseen by experts, and inspired by none other than the expert Julia Child herself, or at least by her library.

Although the Sifter does not contain actual texts or recipes, it does collect the bibliographic data of thousands of such books, a treasury for scholars, researchers, and historians. The primary force behind the project, Barbara Wheaton, was a neighbor of Julia Childs’ in the early 1960s and used Childs’ library and Harvard University’s Schlesinger Library Culinary Collection (where she is now an honorary curator) to become “one of the best-known scholars of culinary history.” Her story illustrates how a recent wealth of culinary scholarship did not just suddenly appear but has been germinating for decades. The Sifter is the result of “Wheaton’s 50 years of labor.”

Wheaton launched the site in July with the help of a team of scholars and her children, Joe and Catherine. The Sifter contains “more than a thousand years of European and U.S. cookbooks, from the medieval Latin De Re Culinaria, published in 800, to The Romance of Candy, a 1938 treatise on British sweets.” It also collects bibliographic data on cookbooks, in their original languages, from around the world. Wheaton hopes The Sifter will generate new areas of research into the history of what may be at once the most universal of all human activities and the most culturally, regionally, and historically particular. Perhaps a silver lining of so many years of scholarly neglect is that there is now so much work for food historians to do. Get started at The Sifter here.

via Atlas Obscura

Related Content:

An Archive of Handwritten Traditional Mexican Cookbooks Is Now Online

Historic Mexican Recipes Are Now Available as Free Digital Cookbooks: Get Started With Dessert

An Archive of 3,000 Vintage Cookbooks Lets You Travel Back Through Culinary Time

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

A Database of 5,000 Historical Cookbooks–Covering 1,000 Years of Food History–Is Now Online is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/3bqdn6N

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment