The Story of Ziggy Stardust Gets Chronicled in a New Graphic Novel, Featuring a Forward by Neil Gaiman

Film has always been a medium that seeks to entertain as well as edify, framing thrills and chills for profit, and framing compositions deserving of the label of “art.” Very often it has done both at the same time. Every casual student of the medium will, at least, admit this much. But never have the differences between movie art and entertainment seemed as magnified and polarized as they are now, in the midst of debates about comic book franchises and the fine art we call cinema.

Whatever the reasons, film has not reached the détente between art and entertainment achieved by popular music—another medium dependent on late-19th/20th century recording technologies and born of a thoroughly modern commercial matrix. Of course, not all pop aspires to art. But the idea that music can be hugely entertaining—drawing on the “low” genres of fantasy, science fiction, and comic books—and also worthy of cultural immortality has become uncontroversial in large part because of the career of one musician.

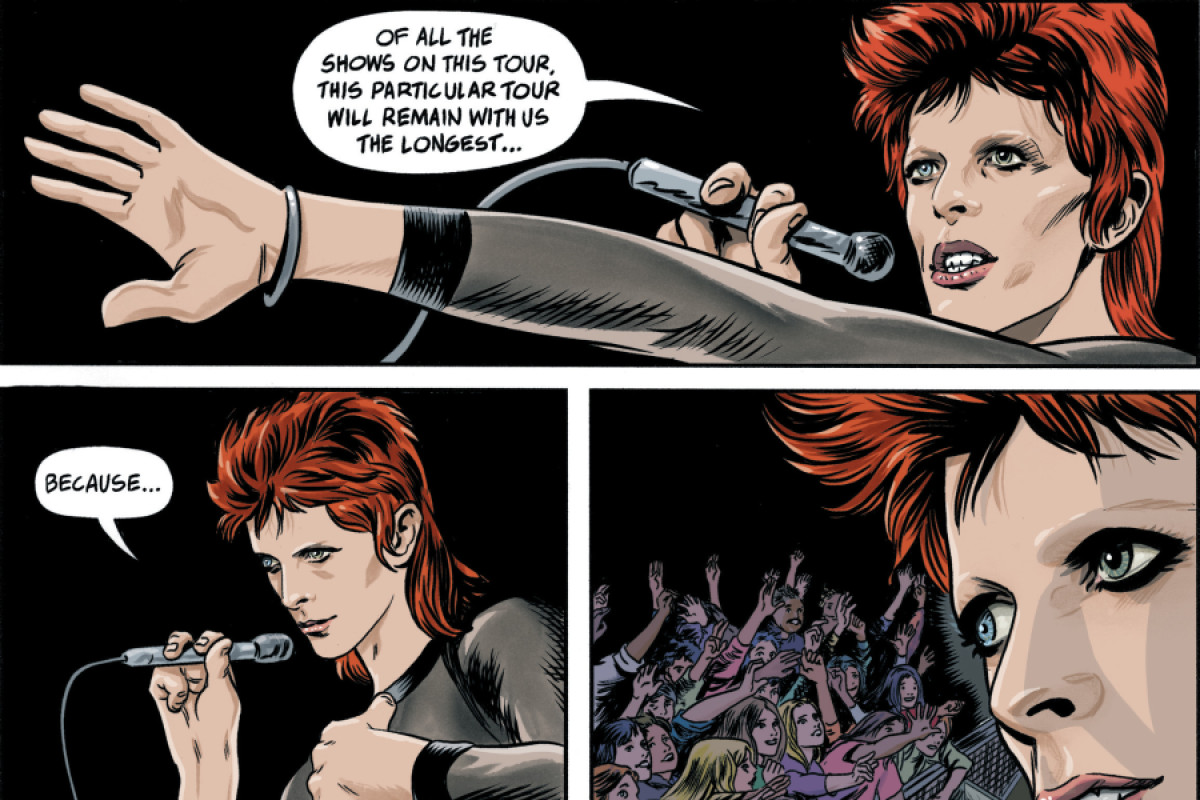

David Bowie, rock and roll’s original space alien superhero, used his bankable personae through the decades to give credence to the idea of “art rock,” to realize its glam possibilities, to turn the rock auteur into an actor. He learned from a host of experimenters, both his direct influences and his spiritual predecessors. And he inspired a legion of successors who weren’t afraid to play characters in their work, to mix interests in philosophy, literature, and the occult with the flamboyant, campy styles of the comics. (A mix comics themselves played with in both popular and underground manifestations.)

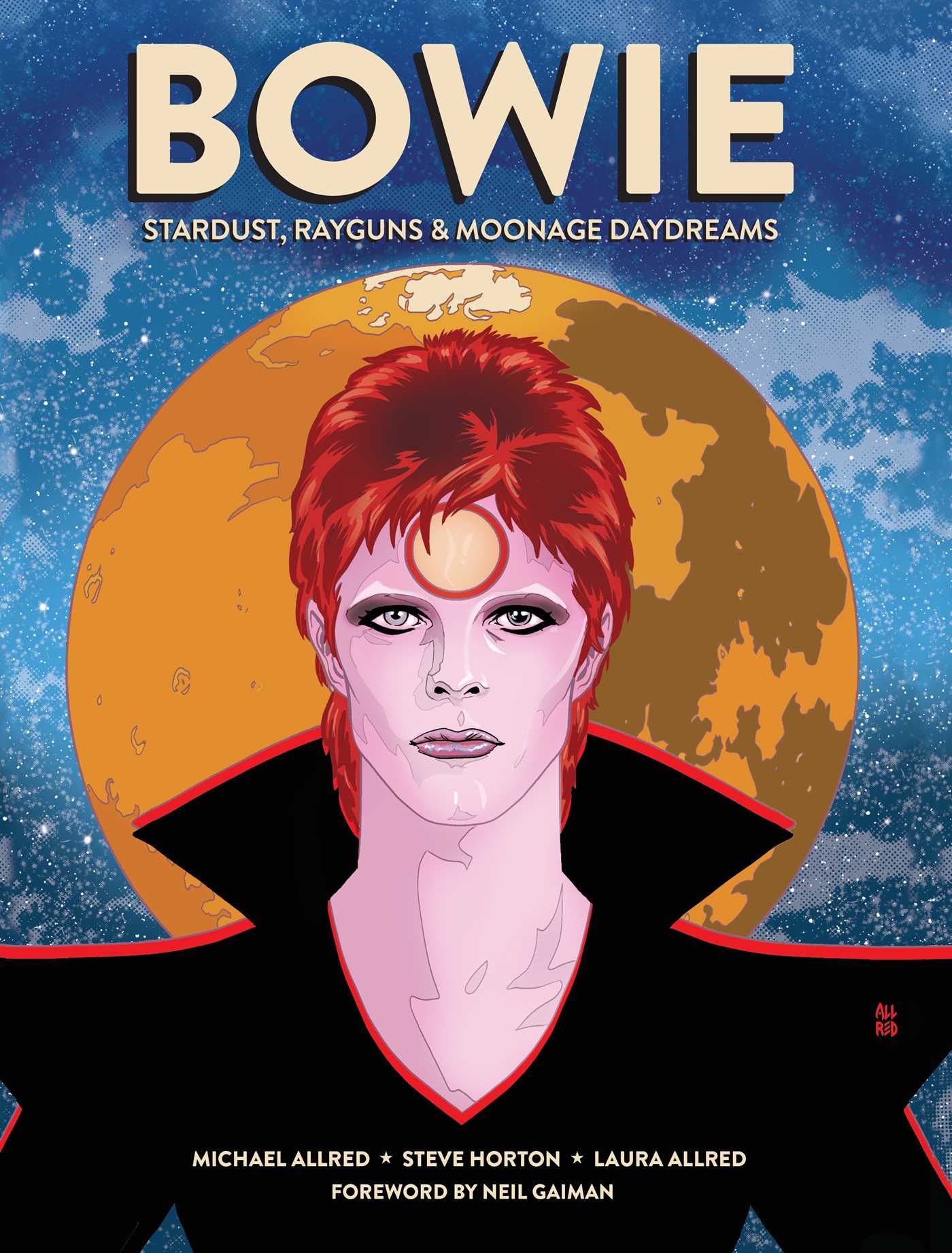

Bowie embodied the future when he appeared on the scene as Ziggy in 1972, after years of laboring in obscurity and a few fleeting brushes with fame. “The incarnations of David Bowie were, in themselves, science fictional, “writes Neil Gaiman in the forward to a new graphic novel, BOWIE: Stardust, Rayguns, & Moonage Daydreams, which tells the story of Bowie’s rise as Ziggy. “All I was missing was a Bowie comic,” says Gaiman of his own fandom. “And, missing it, I would draw bad Bowie comics myself.” Ziggy Stardust especially called for such treatment.

Bowie wore the glam rock Martian mask with such commitment no one doubted that he meant it—only what, exactly, he meant by it. “He defied classification,” notes Simon & Schuster, “with his psychedelic aesthetics, his larger-than-life image, and his way of hovering on the border of the surreal.” Fittingly, the comic is drawn by an artist who realized a psychedelic, surrealist creative vision of Neil Gaiman’s: Michael Allred, who worked on the Sandman series.

The story, “part biography and part imagination,” reports Rolling Stone, is written by Steve Horton and colored by Laura Allred. Insight comics will release the book on January 7th, 2020. Preorder a copy here.

via Rolling Stone

Related Content:

96 Drawings of David Bowie by the “World’s Best Comic Artists”: Michel Gondry, Kate Beaton & More

David Bowie Songs Reimagined as Pulp Fiction Book Covers: Space Oddity, Heroes, Life on Mars & More

Freddie Mercury Reimagined as Comic Book Heroes

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

The Story of Ziggy Stardust Gets Chronicled in a New Graphic Novel, Featuring a Forward by Neil Gaiman is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/32BL7ZN

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment