Found: A Long Lost Chapter from the World’s Oldest Novel, the 11th-Century Japanese Classic, the Tale of Genji

Henry James’ disparagement of Victorian novels has always struck me as odd. “What do such large loose baggy monsters,” as he called them, “with their queer elements of the accidental and the arbitrary, artistically mean?” The question might be asked of what has often been considered the first modern novel, Miguel de Cervantes’ Don Quixote, a tragic-comic adventure whose first volume ranges over 52 loose, episodic chapters and whose second appeared ten years later to comment explicitly on the first’s success.

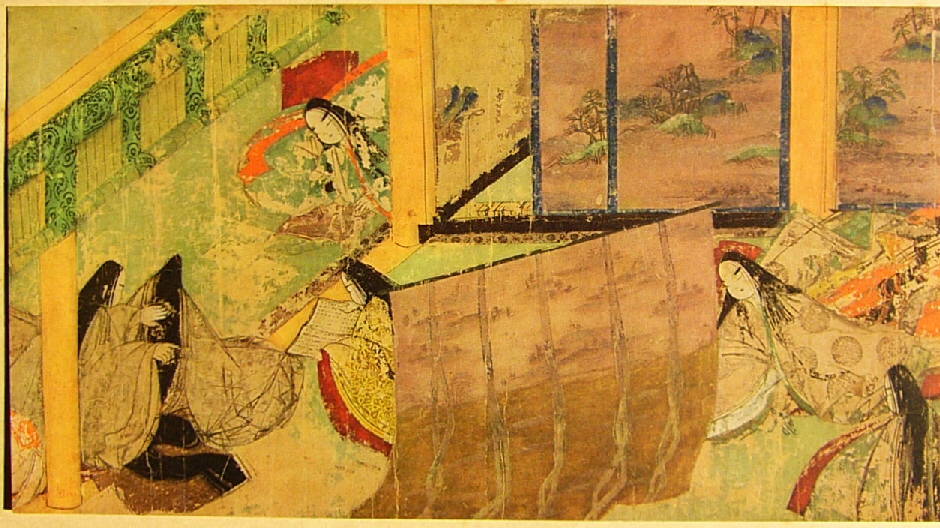

And then, six-hundred years earlier, there appeared what many consider to be the first novel ever written, The Tale of Genji, which “covers almost three quarters of a century,” notes translator Edward Seidensticker in an introduction to his 1976 edition. “The first forty-one chapters have to do with the life and loves of the nobleman known as ‘the shining Genji,’” the son of an emperor. We follow Genji from birth to his 52nd year, then the final ten chapters relate the tale of Kaoru, “who passes in the world as Genji’s son but is really the grandson of his best friend.” (See a 12th-century illustration from the tale above.)

Written by a noblewoman and lady of the court in 11th century Heian Japan, the book’s author is called Murasaki Shikibu, but her real name is unknown. Shikibu “designates an office held by her father”; Murasaki probably derives from the name of a main character in the novel. There is no “conclusive evidence that the Genji was either finished or unfinished at the time, nor is there conclusive evidence that it is finished or unfinished today.” Some chapters have been thought spurious, some deemed missing. No original manuscript exists, and only four of the novel’s 54 chapters have been authenticated as transcriptions from the original text.

That is, until this month, when a “lost”—or previously unknown—chapter surfaced, and “is now the fifth confirmed transcription of the historical novel,” as Hakim Bishara writes at Hyperallergic. “The newly discovered chapter, titled ‘Wakamurasaki,’ depicts Genji’s encounter with Murasaki-no-ue, the young woman who later becomes his wife.” It was discovered by Motofuyu Okochi, The Japan Times reports, “a descendent of the former feudal lord of the Mikawa-Yoshida Domain in Aichi Prefecture.”

The new Genji material appears “in one chapter of a five-chapter work called ‘Aobyoshibon’ (blue cover book), compiled by poet Fujiwara Teika,” who is believed to have transcribed the oldest documented versions of the novel during the Kamakura Period (1185-1333). There is as yet no critical discussion of how this find might change the way scholars read the book, but as a loose baggy monster, it can expand and contract, change its shape and composition, without losing its essential character.

As Seidensticker writes, “Murasaki Shikibu was no Aristotelian, planning her beginning, middle, and end before she set brush to paper. The Genji is full of hesitations and wrong turns and retreats.” Full, in other words, of the meanderings of the mind. (You can read Seidensticker’s translation of the Genji online here.) Another Western admirer of the novel, Jorge Luis Borges, writing of an earlier translation, put it another way: “What interests us is not the exoticism—the horrible word—but rather the human passions… Murasaki’s work is what one would quite precisely call a psychological novel.”

via Hyperallergic

Related Content:

Hand-Colored Photographs of 19th Century Japan

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Found: A Long Lost Chapter from the World’s Oldest Novel, the 11th-Century Japanese Classic, the Tale of Genji is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/32GLZMI

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment