The Provocative Art of Modern Sketch, the Magazine That Captured the Cultural Explosion of 1930s Shanghai

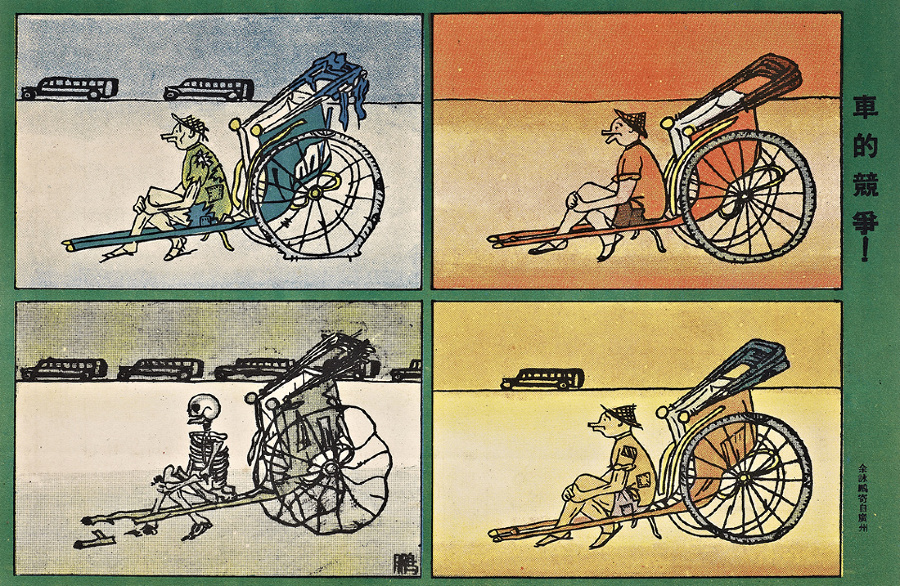

"With its newspapers in every language and scores of radio stations, Shanghai was a media city before its time, celebrated as the Paris of the Orient and 'the wickedest city in the world.'" So British writer J.G. Ballard remembers the Chinese metropolis in which he grew up in his autobiography Miracles of Life. "Shanghai struck me as a magical place, a self-generating fantasy that left my own little mind far behind." Born in 1930, Ballard caught Shanghai at a particularly stimulating time: "Developed on the basis of 'unequal treaties' successively instituted after the First Opium War in 1842," writes MIT's John A. Crespi, Chinese port cities like Shanghai "experienced a welter of technological and demographic changes," including automobiles, skyscrapers, rolled cigarettes, movie theaters coffeehouses, and much else besides.

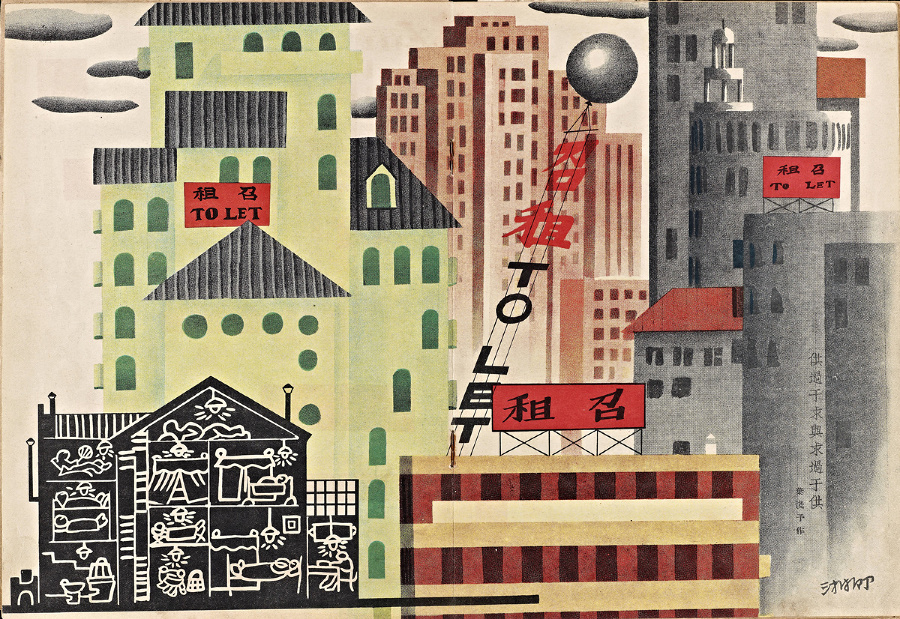

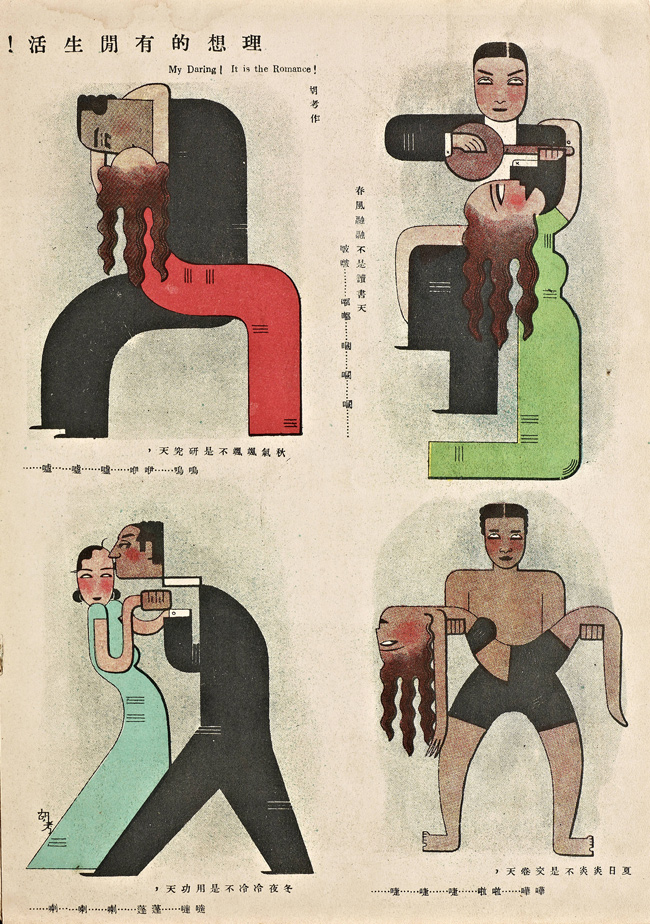

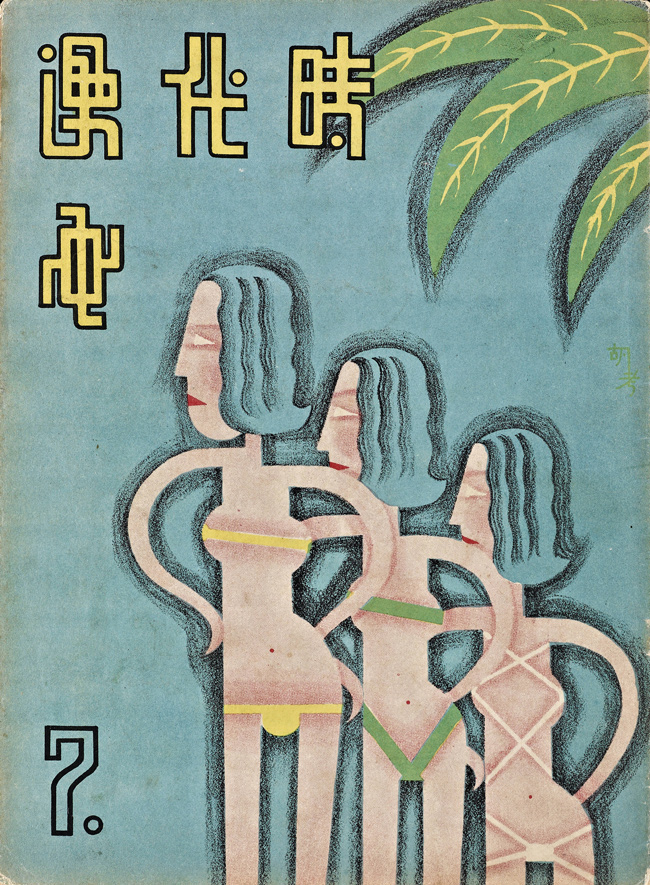

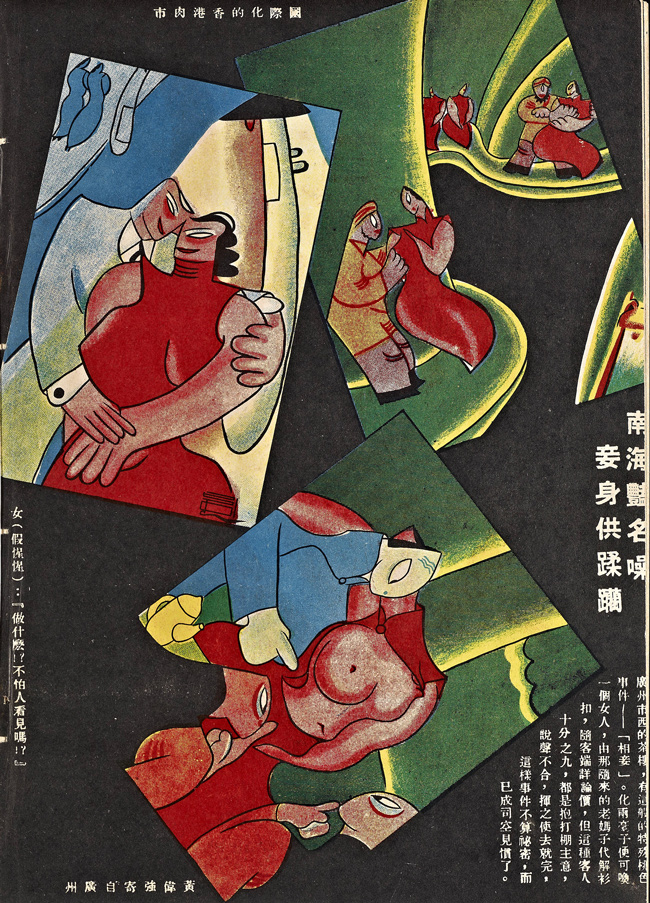

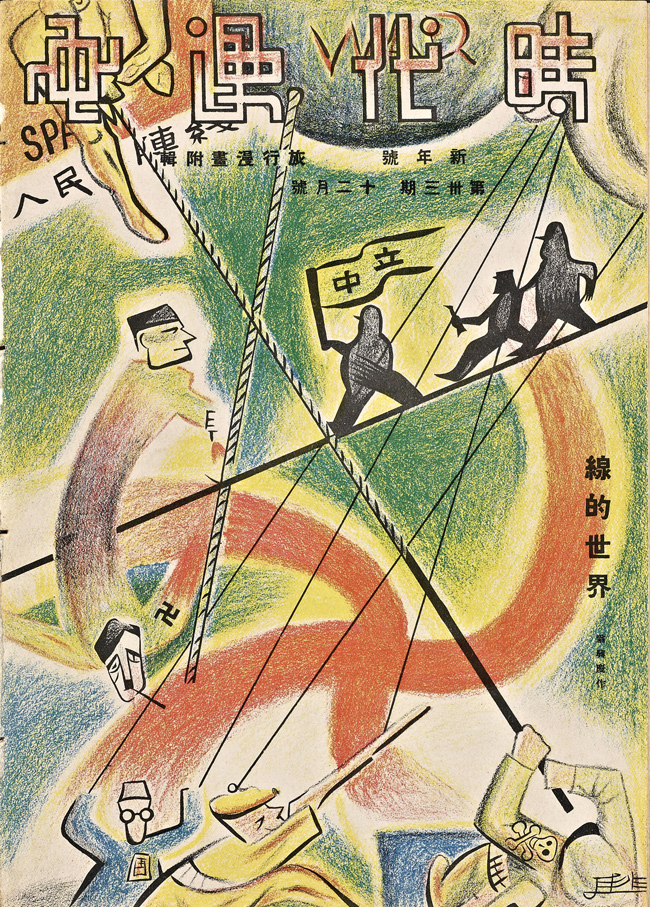

Such heady days also gave rise to media that reflected and critiqued them, and 1930s Shanghai produced no more compelling an example of such a publication than Modern Sketch (????, Shídài Mànhuà).

Among its points of interest, writes Crespi, "one can point to Modern Sketch’s longevity, the quality of its printing, the remarkable eclecticism of its content, and its inclusion of work by young artists who went on to become leaders in China’s 20th-century cultural establishment. But from today’s perspective, most intriguing is the sheer imagistic force with which this magazine captures the crises and contradictions that have defined China’s 20th century as a quintessentially modern era."

Published monthly from January 1934 through June 1937, the magazine first appeared on newsstands just over two decades after the collapse of China’s dynastic system. The modernization-minded May Fourth Movement, nationalist Northern Expedition, and purge of communists by “Generalissimo” Chiang Kai-shek were even more recent memories.

But the relative stability of the "Nanjing Decade" had begun in 1927, and its zeitgeist turned out to be rich soil for a wild cultural flowering in China's coastal cities, none wilder than in Shanghai. To the reading public of this time Modern Sketch offered treatments of material like "eroticized women, foreign aggression — particularly the rise of fascism in Europe and militarized Japan — domestic politics and exploitation, and modernity-at-large," writes Crespi.

The magazine's attitude "could be incisive, bitter, shocking, and cynical. At the very same time it could be elegant, salacious, and preposterous. Its messages might be as simple as child’s play, or cryptically encoded for cultural sophisticates."

Sometimes it didn't encode its messages cryptically enough: as a result of one unflattering depiction of Xu Shiying, China's ambassador to Japan, the authorities suspended publication and detained editor Lu Shaofei. Not that Lu didn't know what he was getting into with Modern Sketch: "On all sides a tense era surrounds us," he wrote in the magazine's inaugural issue. "As it is for the individual, so it is for our country and the world."

As for an answer to the question of whether the strange and tense but enormously fruitful cultural and political moment in which Lu and his collaborators found themselves wold last, "the more one fails to find it, the more that desire grows. Our stance, our single responsibility, then, is to strive!"

You can read more about what project entailed, and see in greater detail its textual and visual results, in Crespi's history of this magazine that strove to capture the everyday reality of life on display in 1930s Shanghai — "though I sometimes wonder," Ballard writes, "if everyday reality was the one element missing from the city."

via 50 Watts

Related content:

China’s New Luminous White Library: A Striking Visual Introduction

Vintage 1930s Japanese Posters Artistically Market the Wonders of Travel

A Curated Collection of Vintage Japanese Magazine Covers (1913-46)

Extensive Archive of Avant-Garde & Modernist Magazines (1890-1939) Now Available Online

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

The Provocative Art of Modern Sketch, the Magazine That Captured the Cultural Explosion of 1930s Shanghai is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/2NegL9c

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment