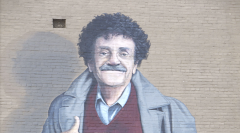

Hear a Radio Opera Narrated by Kurt Vonnegut, Based on His Adaptation of Igor Stravinsky’s 1918 L’Histoire du Soldat

In the legend of Robert Johnson, American bluesman, a deal with the devil brings instant musical genius, and a brief and troubled life in near obscurity. A two-hundred-year-old Russian folktale has similar events in the opposite order: a soldier hands over his violin, and his musical talent, to the devil in exchange for wealth, and several more adventures and reversals before the final, inevitable path to perdition.

This story struck a chord with Igor Stravinsky, who was maybe ahead of his time in seeing a musical deal with the devil as an archetypal subject for popular song. In the first act of his theater piece, “The Soldier’s Story” (L’Histoire du Soldat)—whose libretto by Charles Ferdinand Ramuz adapts the Russian folktale—the soldier tragically relinquishes his ability to turn sorrow into beauty in the first act, perhaps a poignant statement in 1918, when, as Kurt Vonnegut says, “to be a soldier was really something.”

To have served in a war “in which 65 million persons had been mobilized and 35 million were becoming casualties,” to have witnessed the scarifying beginning of modern warfare, meant bearing the stamp of too much reality. In the folktales, we may see the devil as hardship, loss, or greed personified. These are metaphysical morality plays, far removed from current events. But war was potentially upon us all by 1918, Vonnegut suggests, in a terrifying force that devastated soldiers, mowed down civilians by the thousands, and leveled whole cities.

Asked to narrate the Stravinsky piece, Vonnegut declined. He found Ramuz’s treatment of a soldier’s life “preposterous” and unacceptable. So, George Plimpton challenged him to write his own version. He did, in 1993, but rather than make his soldier a musician (“you know, soldiers get rained on, and a violin wouldn’t have a chance”) or a nameless stock character, he plucked a figure out of history—and out of his own nonfiction book The Execution of Private Slovik, published in 1954.

Eddie Slovik was one of at least 30,000 deserters at the Battle of the Bulge. 49 were tried, and only Slovik was executed, at the express order of General Eisenhower. “He was the only person to be executed for cowardice in the face of the enemy since the Civil War,” Vonnegut told New York magazine. “Ike signed his death certificate. They stood him up in front of his comrades, and they shot him.” Vonnegut saw particular malice in the act. “Slovik deserves to be kept alive. If his name had been McCoy or Johnson, I don’t think he would have been shot.”

Instead of The Devil, in Vonnegut’s A Soldier’s Story, we have the character of The General. The novelist's replacement of the original text bothered some when his libretto premiered, with Stravinsky’s music, at Lincoln Center’s Alice Tully Hall in 1993. Responding to the New York Times’ critic, Vonnegut said, “Well, it was a desecration. It was a sacred text, and I dared to fool with it. And some people just find that unbearable. That critic—I spoiled his evening.” In other words, he couldn’t have cared less.

Vonnegut’s libretto with Stravinsky’s music was not recorded for international copyright reasons until 2009, but he did record a version—playing The General himself—with music by Dave Soldier (hear it at the top). This recording of “A Soldier’s Story” appeared on the album Ice-9 Ballads, a compilation of lyrics adapted, and narrated, by Vonnegut from his novel Cat’s Cradle, with music by Soldier. Hear that full album here. And purchase a copy An American Soldier’s Tale: Histoire Du Soldat, with text by Kurt Vonnegut, with music by Igor Stravinsky, performed by the American Chamber Winds, and conducted by David A. Waybright. You can hear samples in this playlist.

Related Content:

Roger Waters Adapts and Narrates Igor Stravinsky’s Theatrical Piece, The Soldier’s Story

A New Kurt Vonnegut Museum Opens in Indianapolis … Right in Time for Banned Books Week

The Night When Charlie Parker Played for Igor Stravinsky (1951)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness.

Hear a Radio Opera Narrated by Kurt Vonnegut, Based on His Adaptation of Igor Stravinsky’s 1918 L’Histoire du Soldat is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/33b94aj

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment