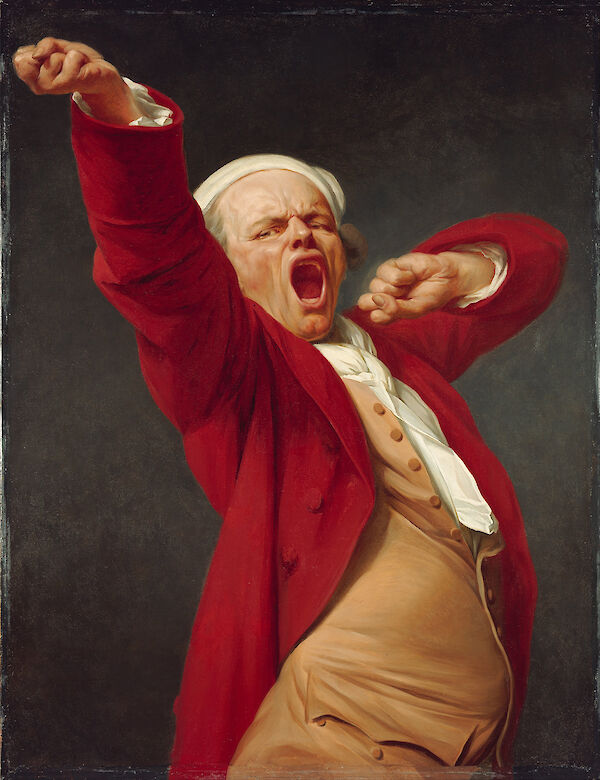

We all know him, the dapper cross between a smarmy office bro and smug, pull-my-finger uncle; leaning on his walking stick, hat pushed back at a rakish angle, pointing at the viewer with a leer.… The 17th-century painting, titled Self-Portrait in the Guise of a Mocker, enjoyed a brief but rich second life for a couple years as a 21st century meme, first appearing online in a 2009 image macro with the caption “Disregard Females, Acquire Currency,” an overly stuffy, thus hilarious, rephrasing of Notorious B.I.G.’s “Get Money” lyrics. Thousands of imitations followed. Within a couple years, Steve Buscemi’s face got photoshopped in place of the grinning bon vivant, and the meme began its decline.

But whose face was it, pre-Buscemi, giving us that toothy grin and point, “like a man catching sight of an old friend across a crowded room,” the Public Domain Review writes, “or a politician trying to charm a voter.” The gentleman in question, in fact, happened to be the artist, Joseph Ducreux, a highly skilled oil painter whose miniature of Marie Antoinette in 1769 won him a baronetcy and the title of primer peintre de la reine (First Painter to the Queen).

This was an honor not given to any old slouch. Ducreux worked alongside such masters as Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun and Jacques-Louis David, despite the fact that he was not a member of the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture, unheard of at the time for a court painter.

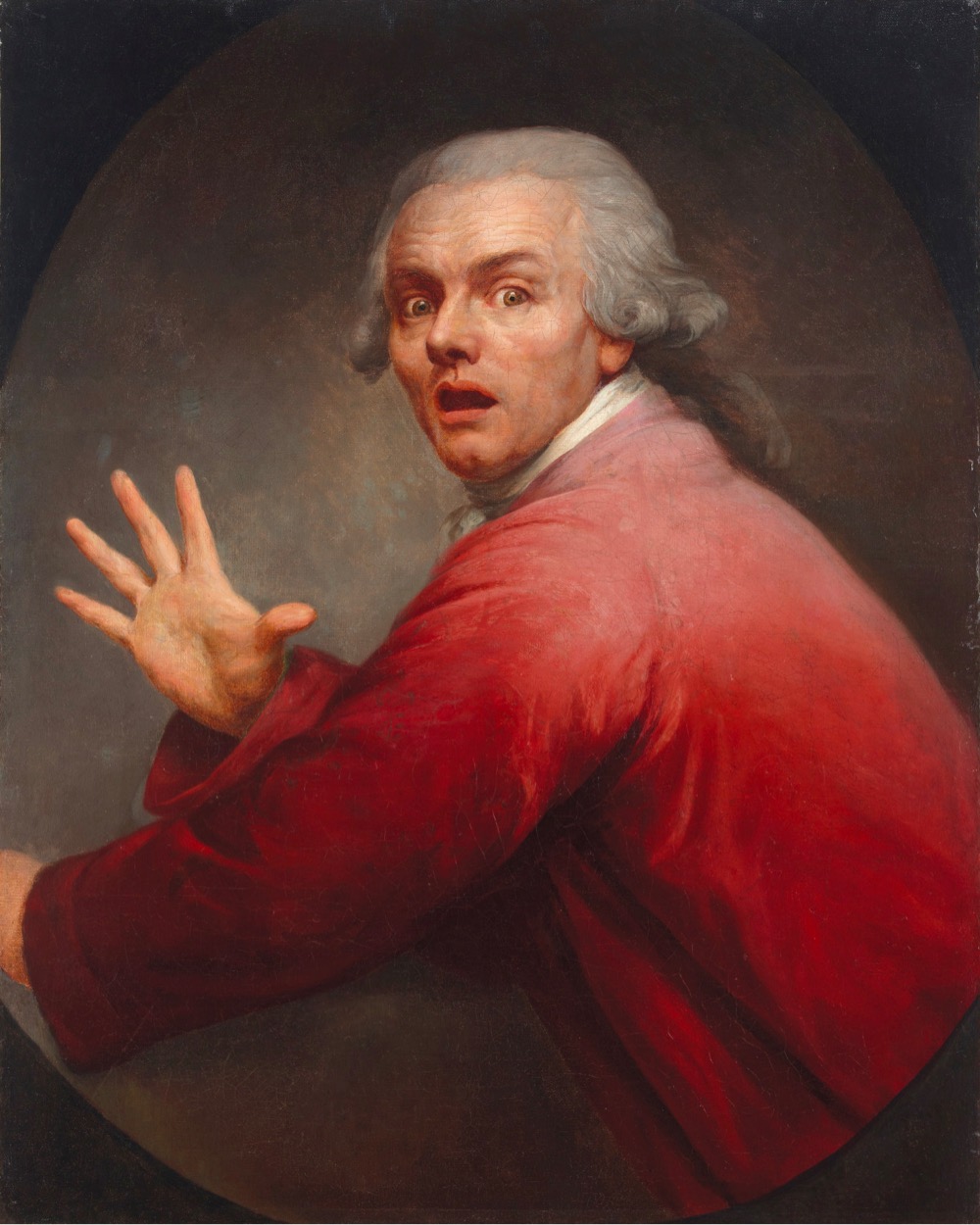

During the French Revolution, Ducreux hid out in London, where he made the last portrait of Louis XVI before the king’s beheading. Afterward, he returned and, through his friendship with David, resumed his career as a portrait painter, as well as an eccentric self-portraitist, an avocation he’d taken up in the 1780s and 90s to satisfy his curiosity about the theory of physiognomy, a pseudoscience that attempted to divine a person’s character and personality from their facial expressions and bodily postures.

These were remarkable paintings for their time, but they were not made with Tumblr or Twitter in mind. Given that they were made before the age of photography and painted on large canvases in oils, the process of creating these goofy selfies would have been painstaking and time-consuming — hardly the kind of effort a working artist applies to a joke.

Humorous as they are, and no doubt Ducreux had a healthy sense of humor, the portraits were also meant to serve a scientific purpose of a sort, and they show an artist pushing past the conservative traditions of portraiture in his day, chafing at the sedate royal postures and placid expressions that were supposed to telegraph the aristocracy’s inner nobility. We might suspect that throughout his career as a court painter, Ducreux had reasons to suspect otherwise about his subjects. But he only had permission to practice his theories on himself.

Related Content:

The Intimacy of Frida Kahlo’s Self-Portraits: A Video Essay

Vincent Van Gogh’s Self Portraits: Explore & Download a Collection of 17 Paintings Free Online

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

The Eccentric Self-Portraits of 18th Century Painter Joseph Ducreux, is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook and Twitter, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/31zLcS4

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment