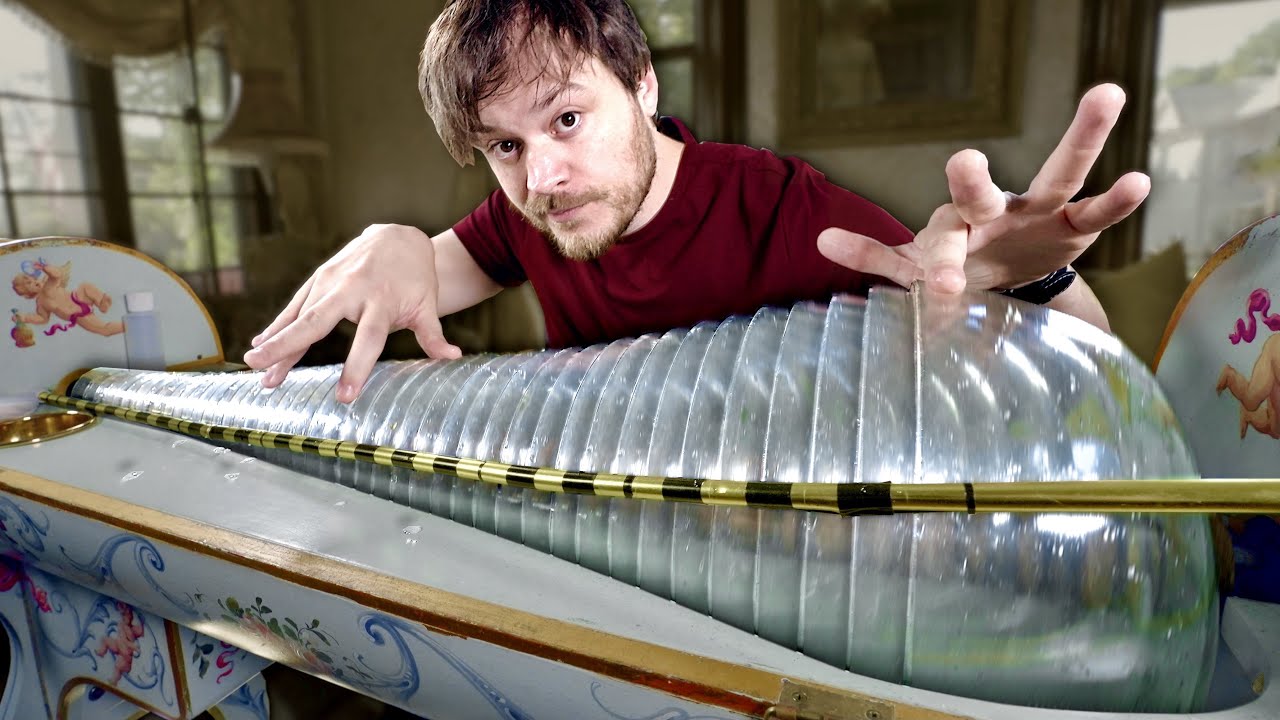

We’re all familiar with keyboard instruments. Many of us have also heard (or indeed made) music, of a kind, with the rims of wine glasses. But to unite the two required the truly American combination of genius, wherewithal, and penchant for folly found in one historical figure above all: Benjamin Franklin. As we’ve previously noted here on Open Culture, the musically inclined Franklin invented an instrument called the glass armonica (alternatively “glass harmonica”) — or rather he re-invented it, having seen and heard an early example played in London. Essentially a series of differently sized bowls arranged from large to small, all rotating on a shaft, the glass armonica allows its player to make polyphonic music of a downright celestial nature.

The playing, however, is easier written about than done. You can see that for yourself in the video above, in which guitarist Rob Scallon visits musician-preservationist Dennis James. Not only does James play a glass armonica, he plays a glass armonica he built himself — and has presumably rebuilt a few times as well, given its scarcely believable fragility.

Transportation presents its challenges, but so does the act of playing, which requires a routine of hand-washing (and subsequent re-wetting, with distilled water only) that even the coronavirus hasn’t got most of us used to. But even in the hands of a first-timer like Scallon, who makes sure to take his turn at the keyboard-of-bowls, the glass armonica sounds like no other instrument even most of us in the 21st century have heard. In the hands of one of its few living virtuosos, of course, the glass armonica is something else entirely.

“If this piece didn’t exist,” says James, holding a piece of sheet music, “I wouldn’t be sitting here.” He refers to Adagio & Rondo for glass armonica in C minor (KV 617), composed by none other than Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. “In 1791, the last year of his life, Mozart wrote a piece for the German armonica player, Marianne Kirchgässner,” writes Timoty Judd at The Listeners’ Club. Like every glass armonica piece, according to James, one ends it by dropping suddenly into complete silence: “It’s the only instrument, up until that point, that could to that: die away to absolutely nothing.” Alas, writes James, not long after the debut of Mozart’s composition rumors circulated that “the strange, crystalline tones of Benjamin Franklin’s new instrument were a threat to public health.” A shame though that seems today, it does suit the multitalented Franklin’s ancillary reputation as an inveterate troublemaker.

Related Content:

Hear the Cristal Baschet, an Enchanting Organ Made of Wood, Metal & Glass, and Played with Wet Hands

Bach’s Most Famous Organ Piece Played on Wine Glasses

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Behold the Glass Armonica, the Unbelievably Fragile Instrument Invented by Benjamin Franklin is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook and Twitter, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/3ls6JDx

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment