How Peter Jackson Used Artificial Intelligence to Restore the Video & Audio Featured in The Beatles: Get Back

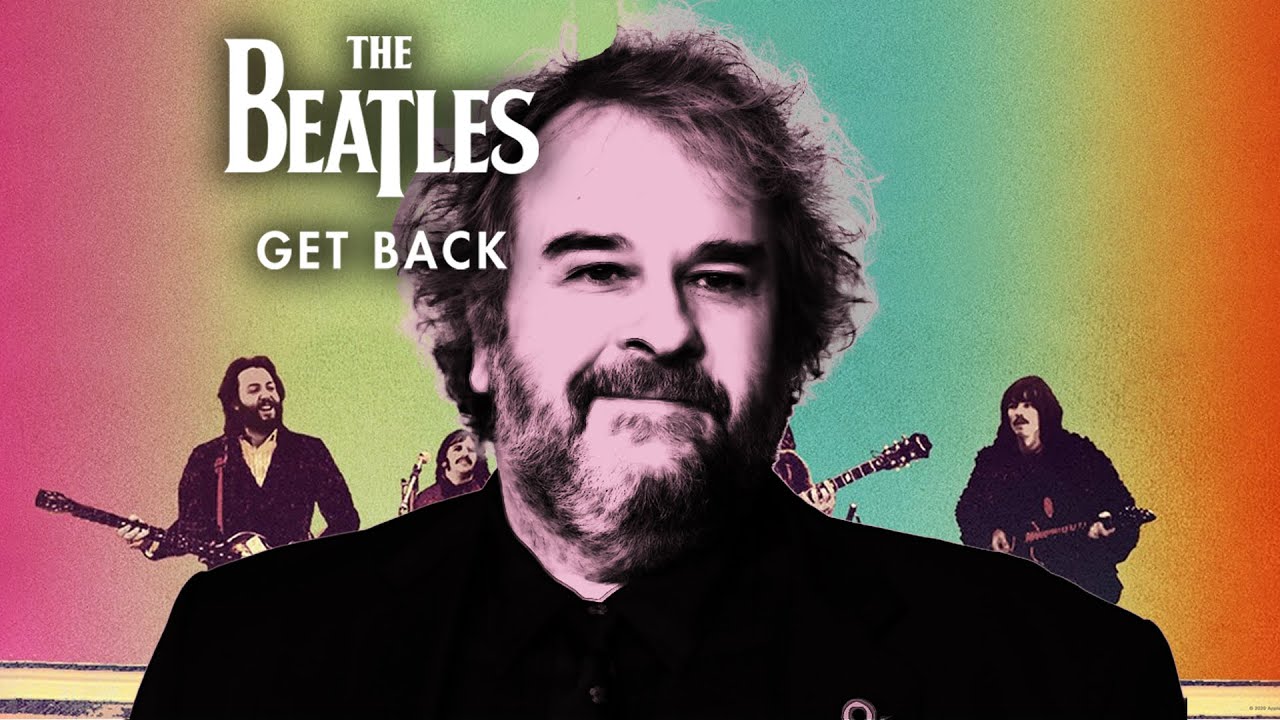

Much has been made in recent years of the “de-aging” processes that allow actors to credibly play characters far younger than themselves. But it has also become possible to de-age film itself, as demonstrated by Peter Jackson’s celebrated new docu-series The Beatles: Get Back. The vast majority of the material that comprises its nearly eight-hour runtime was originally shot in 1969, under the direction of Michael Lindsay-Hogg for the documentary that became Let It Be.

Those who have seen both Linday-Hogg’s and Jackson’s documentaries will notice how much sharper, smoother, and more vivid the very same footage looks in the latter, despite the sixteen-millimeter film having languished for half a century. The kind of visual restoration and enhancement seen in Get Back was made possible by technologies that have only emerged in the past few decades — and previously seen in Jackson’s They Shall Not Grow Old, a documentary acclaimed for its restoration of century-old World War I footage to a time-travel-like degree of verisimilitude.

“You can’t actually just do it with off-the-shelf software,” Jackson explained in an interview about the restoration processes involved in They Shall Not Grow Old. This necessitated marshaling, at his New Zealand company Park Road Post Production, “a department of code writers who write computer code in software.” In other words, a sufficiently ambitious project of visual revitalization — making media from bygone times even more lifelike than it was to begin with — becomes as much a job of traditional film-restoration or visual-effects as of computer programming.

This also goes for the less obvious but no-less-impressive treatment given by Jackson and his team to the audio that came with the Let It Be footage. Recorded in large part monaurally, these tapes presented a formidable production challenge. John, Paul, George, and Ringo’s instruments share a single track with their voices — and not just their singing voices, but their speaking ones as well. On first listen, this renders many of their conversations inaudible, and probably by design: “If they were in a conversation,” said Jackson, they would turn their amps up loud and they’d strum the guitar.”

This means of keeping their words from Lindsay-Hogg and his crew worked well enough in the wholly analog late 1960s, but it has proven no match for the artificial intelligence/machine learning of the 2020s. “We devised a technology that is called demixing,” said Jackson. “You teach the computer what a guitar sounds like, you teach them what a human voice sounds like, you teach it what a drum sounds like, you teach it what a bass sounds like.” Supplied with enough sonic data, the system eventually learned to distinguish from one another not just the sounds of the Beatles’ instruments but of their voices as well.

Hence, in addition to Get Back‘s revelatory musical moments, its many once-private but now crisply audible exchanges between the Fab Four. “Oh, you’re recording our conversation?” George Harrison at one point asks Lindsay-Hogg in a characteristic tone of faux surprise. But if he could hear the recordings today, his surprise would surely be real.

Related Content:

Watch Paul McCartney Compose The Beatles Classic “Get Back” Out of Thin Air (1969)

Peter Jackson Gives Us an Enticing Glimpse of His Upcoming Beatles Documentary The Beatles: Get Back

Artificial Intelligence Program Tries to Write a Beatles Song: Listen to “Daddy’s Car”

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

How Peter Jackson Used Artificial Intelligence to Restore the Video & Audio Featured in The Beatles: Get Back is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook and Twitter, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/31t67q1

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment