It doesn’t take children long to suspect that Santa Claus is actually their parents. But if Mom and Dad demonstrate sufficient commitment to the fantasy, so will the kids. This must have held even truer for the family of the 20th century’s most celebrated creator of fantasies, J. R. R. Tolkien. Before Tolkien had begun writing The Hobbit, let alone the Lord of the Rings trilogy, he was honing his signature storytelling and world-building skills by writing letters from Father Christmas. The toddler John Tolkien and his infant brother Michael received the first in 1920, just after their Great War veteran father was demobilized from the army and made the youngest professor at the University of Leeds. Another would come each and every Christmas until 1943, two more children and much of a life’s work later.

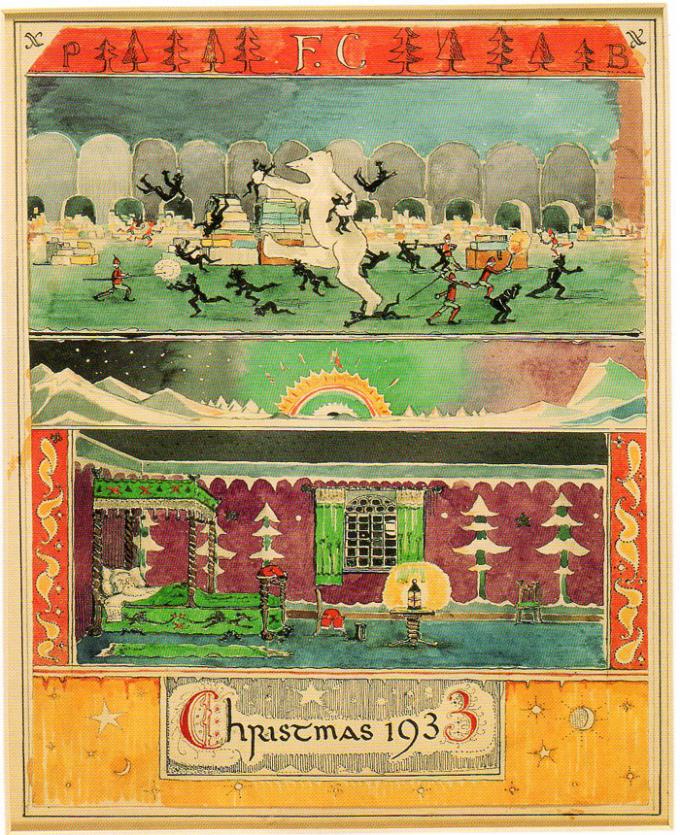

Every year, Tolkien’s Father Christmas had a great deal to report to John, Michael, and later Christopher and Priscilla. Apart from the usual hassle of assembling and delivering gifts, he had to contend with a host of other challenges including but not limited to attacks by marauding goblins and the accidental destruction of the moon.

The cast of characters also includes an unreliable polar-bear assistant and his cubs Paksu and Valkotukka, the sound of whose names hints at Tolkien’s interest in language and myth. Since the publication of the collected Letters From Father Christmas a few years after Tolkien’s death, enthusiasts have identified many traces of the qualities that would later emerge, fully developed, in his novels. The spirit of adventure is there, of course, but so is the humor.

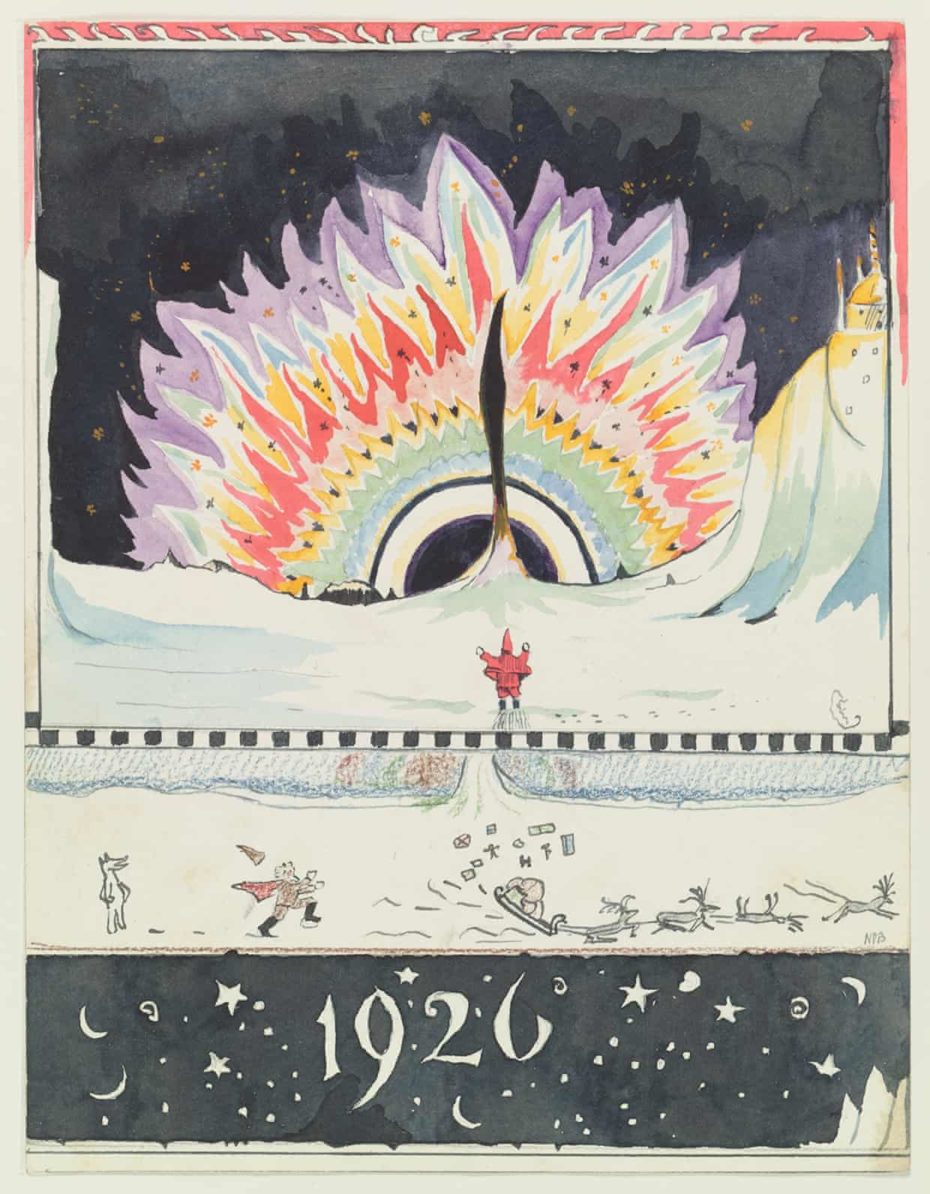

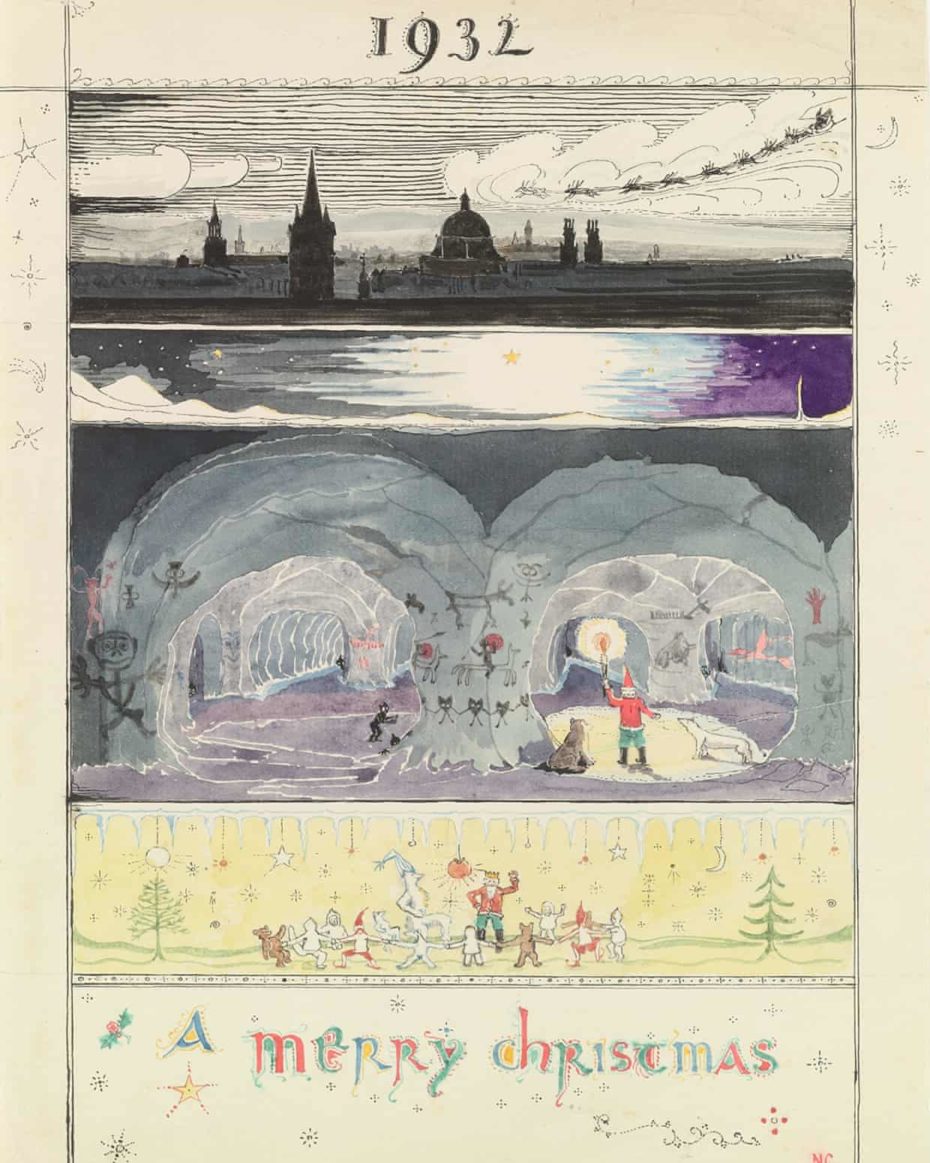

Understanding seemingly from the first how to fire up a young reader’s imagination, the multitalented Tolkien accompanied each letter from Father Christmas with an illustration. Colorful and evocative, these works of art depict the scenes of both mishap and revelry described in the correspondence (itself stamped with a Tolkien-designed seal from the North Pole). How intensely must young John, Michael, Christopher, and Priscilla have anticipated these missives in the weeks — even months — leading up to Christmas. And how astonishing it must have been, upon much later reflection, to realize what attention their father had devoted to this family project. Growing up Tolkien no doubt had its downsides, as relation to any famous writer does, but unmemorable holidays can’t have been one of them.

Related Content:

Read J. R. R. Tolkien’s “Letter From Father Christmas” To His Young Children

Discover J. R .R. Tolkien’s Personal Book Cover Designs for The Lord of the Rings Trilogy

The Only Drawing from Maurice Sendak’s Short-Lived Attempt to Illustrate The Hobbit

110 Drawings and Paintings by J.R.R. Tolkien: Of Middle-Earth and Beyond

When Salvador Dalí Created Christmas Cards That Were Too Avant-Garde for Hallmark (1960)

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

J.R.R. Tolkien Sent Illustrated Letters from Father Christmas to His Kids Every Year (1920-1943) is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook and Twitter, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/32wLiL2

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment